Blue Print

The Game: You are the intrepid, barbershop-quartet-suited J.J. (hey, it’s better than being O.J.!), out to save a damsel in distress from a pursuing monster. How does a guy in a little striped suit do this? By building a mobile, tennis-ball-launching contraption to dispatch said dastardly monster, naturally. The catch? The eight pieces of your mechanical creation are hidden somewhere among ten little houses in a maze – and those houses that don’t contain parts of your machine contain a bomb that must be dumped into the bomb pit immediately (else they’ll explode and kill J.J.). Critters also roam the maze to annoy you, including one pesky monster who will prematurely jump on the “start” button, rattling your still-unfinished machine to bits. If you don’t build your Rube Goldberg gizmo in time, the monster catches the damsel and you lose a life. (Bally/Midway, 1982)

The Game: You are the intrepid, barbershop-quartet-suited J.J. (hey, it’s better than being O.J.!), out to save a damsel in distress from a pursuing monster. How does a guy in a little striped suit do this? By building a mobile, tennis-ball-launching contraption to dispatch said dastardly monster, naturally. The catch? The eight pieces of your mechanical creation are hidden somewhere among ten little houses in a maze – and those houses that don’t contain parts of your machine contain a bomb that must be dumped into the bomb pit immediately (else they’ll explode and kill J.J.). Critters also roam the maze to annoy you, including one pesky monster who will prematurely jump on the “start” button, rattling your still-unfinished machine to bits. If you don’t build your Rube Goldberg gizmo in time, the monster catches the damsel and you lose a life. (Bally/Midway, 1982)

Memories: Fun little game, this Blue Print. Perhaps somewhat like the rodent protagonist of Mappy, J.J. seemed to be primed for some kind of merchandising that never happened.

Bagman

The Game: You’re a thief trying to make away with all the loot buried in a complex maze of interconnected mines and shafts, and you’d get away with it if it weren’t for some pesky cops who are hot on your trail. You can drop bags of money on them from a level above, or temporarily brain them with a pick, and they’ll occasionally also bumble into open mine shafts of their own accord. In any of these events, they vanish for a little while to recover before reappearing. But any of these things will do you in too! (Stern/Seeburg [under license from Valadon Automation], 1982)

The Game: You’re a thief trying to make away with all the loot buried in a complex maze of interconnected mines and shafts, and you’d get away with it if it weren’t for some pesky cops who are hot on your trail. You can drop bags of money on them from a level above, or temporarily brain them with a pick, and they’ll occasionally also bumble into open mine shafts of their own accord. In any of these events, they vanish for a little while to recover before reappearing. But any of these things will do you in too! (Stern/Seeburg [under license from Valadon Automation], 1982)

Memories: Bagman was a very addictive and fun variation on the ladder-climing format that had become familiar in the space of just one year. Despite putting the player in the role of a crook, the worst behavior this game could possibly encourage would be slapstick, Keystone Kops-type violence (wouldn’t it be great if there were a bunch of comically clumsy cops, and wouldn’t it be great if they brought beer – really good beer?). It’s a very cute and playable game.

The Amazing Adventures Of Mr. F. Lea

The Game: Help Mr. F. Lea get to the top in this dog-eat-dog world. Cross a treacherous yard full of lawn-mowers (and helpfully slow-moving dogs), swing from tail to tail until you’ve jumped on every dog on the screen, scale the big dog’s back and jump over his spots, and climb to the top of Dog Hollow while avoiding the dog toys and bones being thrown at you from the top of the screen. You’d better be itching to win. (Pacific Novelty, 1982)

The Game: Help Mr. F. Lea get to the top in this dog-eat-dog world. Cross a treacherous yard full of lawn-mowers (and helpfully slow-moving dogs), swing from tail to tail until you’ve jumped on every dog on the screen, scale the big dog’s back and jump over his spots, and climb to the top of Dog Hollow while avoiding the dog toys and bones being thrown at you from the top of the screen. You’d better be itching to win. (Pacific Novelty, 1982)

Memories: An oddball specimen from the dawn of the age of video game litigation, Mr. F. Lea would appear to have slipped through the cracks without attracting the wrath of the legal beagles. How that happened, we can’t even guess, for the game’s four stages strongly resemble Frogger, Donkey Kong and elements of Jungle Hunt. It’s like the hottest games in the average 1982 arcade…as played by a quirky cover band.

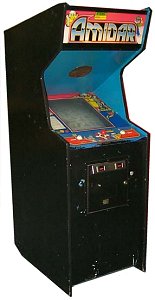

Amidar

The Game: I’ll try to explain this as best I can. You’re a paintroller (recent escapee from Make Trax?) beseiged by pigs. Or a gorilla pursued by natives. Or something like that. It depends on which level you’re playing. You must try to enclose as many of the spaces in the game area as possible, in a zig-zagging pattern. This, the attract mode wisely advises us, is “Amidar movement.” You have one way to avoid an imminent head-on collision – you can hit the jump button, which doesn’t make you jump, but forces everything else on the board to jump. Enclosing all of the available spaces advances you to the next level, with different animal enemies. (Stern [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: I’ll try to explain this as best I can. You’re a paintroller (recent escapee from Make Trax?) beseiged by pigs. Or a gorilla pursued by natives. Or something like that. It depends on which level you’re playing. You must try to enclose as many of the spaces in the game area as possible, in a zig-zagging pattern. This, the attract mode wisely advises us, is “Amidar movement.” You have one way to avoid an imminent head-on collision – you can hit the jump button, which doesn’t make you jump, but forces everything else on the board to jump. Enclosing all of the available spaces advances you to the next level, with different animal enemies. (Stern [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: My God. Who programmed this game, and what were they smoking? I mean, okay, the enclosing-of-spaces thing is nothing new – look at Qix. But paintrollers versus pigs? Gorillas versus nasty natives? Oh well. I suppose it makes about as much sense as Exidy’s very similar Pepper II, of which more another time.

Commodore VIC-20

The VIC-20 was a direct descendant of Commodore’s PET computer – popular with educators, school districts and students who, like myself, got their first computer experience on one of Commodore’s all-in-one monochrome machines of the future. The VIC-20 was, in fact, developed under the code-name of “Micro PET,” and it was designed to be the future in a convenient, compact, user-friendly package.

The VIC-20 was a direct descendant of Commodore’s PET computer – popular with educators, school districts and students who, like myself, got their first computer experience on one of Commodore’s all-in-one monochrome machines of the future. The VIC-20 was, in fact, developed under the code-name of “Micro PET,” and it was designed to be the future in a convenient, compact, user-friendly package.

It’s funny how that future kept changing. In 1981, when the VIC-20 was introduced by Commodore, America was in the thrall of video game mania, or at least more specifically Pac-Man mania. Atari’s star was rising, with no limit in sight; everyone and their  brother, it seemed, was getting into the business of arcade games, or making cartridges for the Atari 2600. New consoles were being developed. And the most bare-bones home computer setup could scarcely be had for $500. The Apple II was already around, certainly, but even the most basic Apple setup fetched nearly $1,500 at the time. Atari’s home computers and their competitors from Texas Instruments could be had for less than a thousand, but often in such bare-bones form that getting a more fully-featured computer setup would often bring the price point back up to a grand.

brother, it seemed, was getting into the business of arcade games, or making cartridges for the Atari 2600. New consoles were being developed. And the most bare-bones home computer setup could scarcely be had for $500. The Apple II was already around, certainly, but even the most basic Apple setup fetched nearly $1,500 at the time. Atari’s home computers and their competitors from Texas Instruments could be had for less than a thousand, but often in such bare-bones form that getting a more fully-featured computer setup would often bring the price point back up to a grand.

And then Commodore introduced the VIC-20. With a price tag lighter than $300 in most areas, and a retail network that included such outlets as Sears and Toys R Us, the VIC-20 may have also been bare-bones upon arrival – but for $300, it could afford to be. Optional items such as disk drives, printers and the blazing fast 300 baud VIC Modem could be added on, for a price, naturally. But for a basic machine that could give kids (and their parents) some hands-on computer learning experience, and a machine that could play colorful games to boot, $300 was an insanely competitive price point, and many consumers took Commodore up on the offer.

And the VIC-20 was surely the machine of the future. Its game cartridges – the software we’ll be focusing on the most in this archive – were vast chunks of plastic with an impressively wide connector that surely meant there was more program, or more fun – essentially, more value – going on than there was with a little thing like an Atari 2600 cartridge. The VIC-20’s all-in-one casing and easy hookup were certainly a sign of the future too. Surely this was how a home computer was meant to be.

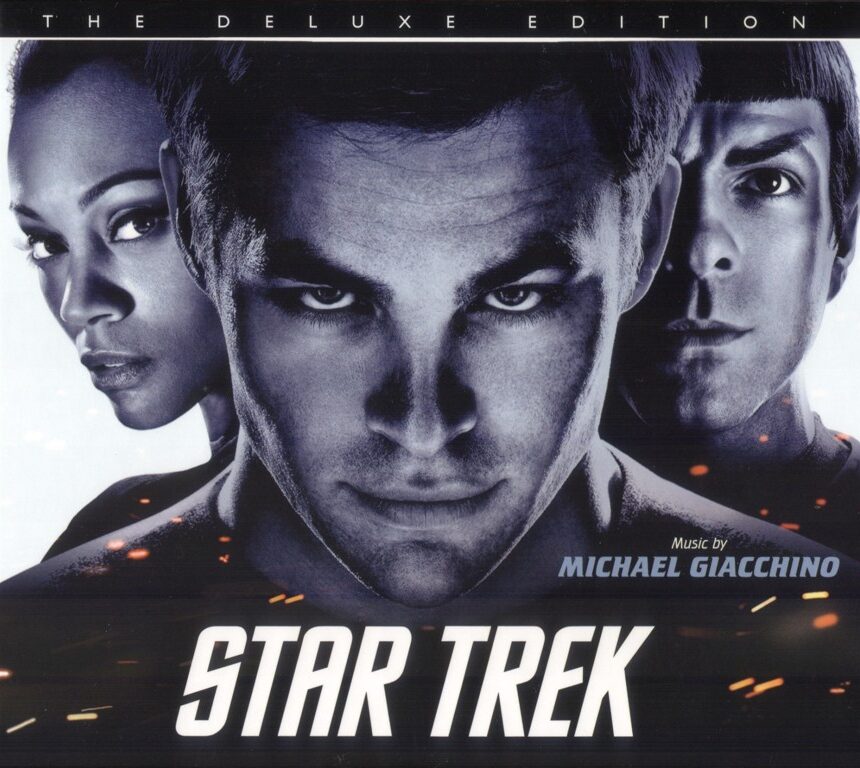

Futuristic advertising was in order for Commodore’s wildly successful new computer as well. While his erstwhile Star Trek crewmate Leonard Nimoy extolled the virtues of the Odyssey2 video game console in TV commercials, William Shatner endorsed the VIC-20, declaring it to be the computer of the future. Even with only 5K of on-board RAM (expandable with an add-on memory module), how could the VIC-20 not be the futuristic marvel that Captain Kirk himself described? And with major third-party software publishers like Imagic and Parker Brothers making games for the VIC, and even Atari’s own Atarisoft division porting popular Atari-licensed games, this was clearly a computer that would stick around. For the future.

Commodore introduced the Commodore 64 home computer a year later.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=123]

Pac-Man

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small yellow dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small yellow dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of  the screen, red power pellets enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Coleco, 1981)

the screen, red power pellets enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Coleco, 1981)

Memories: When Atari’s VCS translation of the immensely popular Pac-Man debuted to almost universal scorn, Coleco’s marketing division must have cheered. The market was primed for a good game of Pac-Man, and with the first in its line of licensed “mini-arcades,” Coleco had just the ticket every kid was looking for.

Bradley Trainer (a.k.a. “Military Battlezone”)

The Game: As the pilot of a Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, you wander the desolate battlefield, trying to wipe out enemy tanks and helictopers without accidentally firing on your own allies. (Atari, under special contract for the United States Army, 1981)

The Game: As the pilot of a Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, you wander the desolate battlefield, trying to wipe out enemy tanks and helictopers without accidentally firing on your own allies. (Atari, under special contract for the United States Army, 1981)

Memories: You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone in the arcade business who’d complain that a game was too good. But Ed Rotberg, designer of Atari’s original 3-D vector graphics tank hit Battlezone, would be the exception. His revolutionary first-person fighting game was impressive enough to attract the attention of the United States Army, and this landed him a very special job he did not want: retooling the game to the Army’s exacting specifications to turn it into a real training simulation.

Ultima

The Game: You set out alone on an adventure spanning countryside, mountains, oceans, towns and dungeons. You can purchase food rations, weapons and armor in the towns, visit Lord British in a castle for his wisdom, maybe a level-up, and your next assignment, or you can venture forth into the dungeons to test your skill against the denizens of the underworld. (California Pacific Computer, 1981)

The Game: You set out alone on an adventure spanning countryside, mountains, oceans, towns and dungeons. You can purchase food rations, weapons and armor in the towns, visit Lord British in a castle for his wisdom, maybe a level-up, and your next assignment, or you can venture forth into the dungeons to test your skill against the denizens of the underworld. (California Pacific Computer, 1981)

Memories: Richard Garriott has said that the first Ultima game – which was originally marketed as Ultimatum – essentially “uses Akalabeth as a subroutine”, and while that may be oversimplifying how much or how little new code Ultima added to the game, it’s essentially true – the dungeons are practically vintage Akalabeth fare, while the towns and the above-ground portions of the game are literally a whole different animal.

Tranquility Base

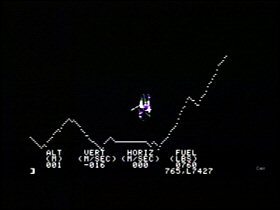

The Game: You are go for landing on the moon – only the moon isn’t there to make it easy for you. Craggy mountains and craters make it difficult for you to find one of the few safe landing spots on the surface, and even when you’re aligned above level ground, your fuel is running out fast. Do you have the right stuff that it’ll take before you can take one giant leap? (Bill Budge, 1981 / re-released by Eduware in 1984)

The Game: You are go for landing on the moon – only the moon isn’t there to make it easy for you. Craggy mountains and craters make it difficult for you to find one of the few safe landing spots on the surface, and even when you’re aligned above level ground, your fuel is running out fast. Do you have the right stuff that it’ll take before you can take one giant leap? (Bill Budge, 1981 / re-released by Eduware in 1984)

Memories: This game was one of the earliest efforts by a budding Apple II programmer named Bill Budge, before he achieved fame as the author of Pinball Construction Set. At the time, Budge was experimenting with interchangeable modules that could be slotted into the code of any number of games, including one for smoothly rotating 3-D wireframe objects – well, smoothly where the Apple II was concerned. The result was this unforgiving homage to Atari’s cult coin-op Lunar Lander.

TI Invaders

The Game: It’s quite simple, really. You’re the pilot of a ground-based mobile weapons platform, and there are buttloads of alien meanies headed right for you. Your only defense is a quartet of shields which are degraded by any weapons fire – yours or theirs – and a quick trigger finger. Occasionally a mothership zips across the top of the screen. When the screen is cleared of invaders, another wave – faster and more aggressive – appears. When you’re out of “lives,” or when the aliens manage to land on Earth…it’s all over. (Texas Instruments, 1981)

The Game: It’s quite simple, really. You’re the pilot of a ground-based mobile weapons platform, and there are buttloads of alien meanies headed right for you. Your only defense is a quartet of shields which are degraded by any weapons fire – yours or theirs – and a quick trigger finger. Occasionally a mothership zips across the top of the screen. When the screen is cleared of invaders, another wave – faster and more aggressive – appears. When you’re out of “lives,” or when the aliens manage to land on Earth…it’s all over. (Texas Instruments, 1981)

Memories: A straightforward, no-frills take on Space Invaders, TI Invaders trumped just about every other home computer version in terms of faithfulness to the source material.

Taxman

The Game: As a round white creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, and apparently somehow tied to the Internal Revenue Service, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score. Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and, after spending some noncorporeal time floating around and contemplating taxation without representation, return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (H.A.L. Labs, 1981)

The Game: As a round white creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, and apparently somehow tied to the Internal Revenue Service, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score. Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and, after spending some noncorporeal time floating around and contemplating taxation without representation, return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (H.A.L. Labs, 1981)

Memories: Alas, the folly of H.A.L. Labs and Taxman. Clearly a copy of Pac-Man – with only the names changed – this game was crippled by keyboard controls that were counterintuitive even back then. The sad thing is, given the graphics and sound limitations of the Apple II, the rest of the game was stellar, a near-perfect port of Pac-Man.

Sneakers

The Game: Alien invaders are descending on your world, taking on unusual forms in the process: sneaker-clad stomping creatures, roaming eyeballs, “H-wing fighters,” flying saucers and more. Try to use their unusual patterns of movement against them and keep them from destroying your fighter. (Sirius Software, 1981)

The Game: Alien invaders are descending on your world, taking on unusual forms in the process: sneaker-clad stomping creatures, roaming eyeballs, “H-wing fighters,” flying saucers and more. Try to use their unusual patterns of movement against them and keep them from destroying your fighter. (Sirius Software, 1981)

Memories: If this description sounds an awful lot like Activision‘s early hit Megamania!, it’s no coincidence – both games attempted to add a dash of whimsy to the basic game play of the ubiquitous arcade sleeper hit, Astro Blaster. Both Sneakers and Megamania! nearly duplicate the unique meandering movement of Astro Blaster‘s alien invaders.

Mouskattack

The Game: Plumber Larry Bain is out to earn his hazard pay, trying to run pipes through a rat-infested maze. This wouldn’t be a problem, except that the rats are as big as he is. He can lay a limited number of traps in the maze that will temporarily stop the rats in their tracks so he can double back and eliminate them, but in the end Larry’s best chance of survival is to stay on the run and fill the maze with plumbing. (Sierra On-Line, 1981)

The Game: Plumber Larry Bain is out to earn his hazard pay, trying to run pipes through a rat-infested maze. This wouldn’t be a problem, except that the rats are as big as he is. He can lay a limited number of traps in the maze that will temporarily stop the rats in their tracks so he can double back and eliminate them, but in the end Larry’s best chance of survival is to stay on the run and fill the maze with plumbing. (Sierra On-Line, 1981)

Memories: Cut from the same “let’s do Pac-Man but make it different enough from Pac-Man that we don’t get sued” cloth as his own Jawbreaker, John Harris strikes again with Mouskattack, which was actually advertised as being “by the author of Jawbreaker,” which may be one of the earliest instances of a game being advertised as something that should be bought on the strength of that programmer’s previous works.

Jawbreaker

The Game: You’re a mobile set of chattering teeth, gobbling up goodies in a maze as jaw-breaking candies pursue you. If you bite down on one of these killer candies, you’ll rack up quite a dental bill (enough to lose a life). You can snag one of four snacks in the corners of the maze and suddenly the tooth-rotting treats become crunchy and vulnerable. Advance to the next level by clearing the maze of dots. (On-Line Systems, 1981)

The Game: You’re a mobile set of chattering teeth, gobbling up goodies in a maze as jaw-breaking candies pursue you. If you bite down on one of these killer candies, you’ll rack up quite a dental bill (enough to lose a life). You can snag one of four snacks in the corners of the maze and suddenly the tooth-rotting treats become crunchy and vulnerable. Advance to the next level by clearing the maze of dots. (On-Line Systems, 1981)

Memories: Atari’s home version of Pac-Man for the Atari 2600 was like a trail of telltale blood in a tank full of pirhanas. It was quickly apparent that there was one wounded one in the group, and other predators quickly closed in for the kill – or, in the case of Pac-Man, provided games for various platforms that duplicated the Pac-Man experience better than Atari could apparently manage to do.

Checkers

The Game: The classic game of strategy is faithfully reproduced on the Apple II. Two armies of twelve men each advance diagonally across the checkerboard, jumping over opponents and attempting to reach the enemy’s home squares to be crowned. Whoever still has pieces still standing at the end of the game wins. (Odessa Software, 1981)

The Game: The classic game of strategy is faithfully reproduced on the Apple II. Two armies of twelve men each advance diagonally across the checkerboard, jumping over opponents and attempting to reach the enemy’s home squares to be crowned. Whoever still has pieces still standing at the end of the game wins. (Odessa Software, 1981)

Memories: At the time of its release, Odessa Software’s Apple version of checkers was a reasonably big deal, since it had been given its “smarts” by one of the leading experts in programming computers to play chess and checkers.

Caverns Of Mars

The Game: The enemy in an interplanetary war has gone underground, and you’re piloting the ship that’s taking the fight to him. But he hasn’t just hidden away in a hole; he’s hidden away in a very well-defended hole. As if it wasn’t already going to be enough of a tight squeeze navigating subterranean caverns on Mars, you’re now sharing that space with enemy ships and any number of other fatal obstacles. (Fortunately, the enemy also leaves copious numbers of helpful fuel depots for you too.) Once you fight your way to the bottom of the cave, you plant charges on the enemy mothership – meaning that now you have to escape the caverns again, and fast. (Atari, 1981)

The Game: The enemy in an interplanetary war has gone underground, and you’re piloting the ship that’s taking the fight to him. But he hasn’t just hidden away in a hole; he’s hidden away in a very well-defended hole. As if it wasn’t already going to be enough of a tight squeeze navigating subterranean caverns on Mars, you’re now sharing that space with enemy ships and any number of other fatal obstacles. (Fortunately, the enemy also leaves copious numbers of helpful fuel depots for you too.) Once you fight your way to the bottom of the cave, you plant charges on the enemy mothership – meaning that now you have to escape the caverns again, and fast. (Atari, 1981)

Memories: Atari wisely realized that some of the best programming talent wasn’t necessarily on its own payroll. With so much of the company’s financial resources devoted to supporting the 2600, this paved the way for the Atari Program Exchange, a program that allowed users to send in their own best work to Atari, who would then list the best of these homebrew games and applications in an official newsletter and handle distribution on cassette and floppy disk.

Infiltrate

The Game: You’re trapped in a multi-story building with hostile forces all around. Your infiltration mission has gone from mere espionage to a battle for survival – a battle you’re probably not going to win. Board elevators to reach the opposite level of the screen to retrieve enemy secrets, all while avoiding enemy agents and trying to shoot them down. (This spy business would be a lot easier if the enemy couldn’t shoot back, but generally they’re better shots than you are.) Then a new prize appears at the opposite end of the screen, sending you on yet another dangerous mission. (Games By Apollo, 1981)

The Game: You’re trapped in a multi-story building with hostile forces all around. Your infiltration mission has gone from mere espionage to a battle for survival – a battle you’re probably not going to win. Board elevators to reach the opposite level of the screen to retrieve enemy secrets, all while avoiding enemy agents and trying to shoot them down. (This spy business would be a lot easier if the enemy couldn’t shoot back, but generally they’re better shots than you are.) Then a new prize appears at the opposite end of the screen, sending you on yet another dangerous mission. (Games By Apollo, 1981)

Memories: A simple Atari 2600 port of the popular computer game Spy’s Demise, Infiltrate simplifies things a bit more than the computer version and keeps players constantly running for their lives. There’s really no win condition – just a grim countdown to the point at which the player is worn down.

Yars’ Revenge

The Game: As the last of a race of spacefaring insects, you must defend yourself from a relentless wave of alien attackers bent on ridding the universe of your race. An alien tracer, deadly to the touch, tracks your every move, though it cannot harm you while you’re in the neutral zone at the center of the screen. You must eat away at the aliens’ shield, which not only reduces their defenses, but builds your energy reserve so you can fire your own powerful weapon, which can wipe out the alien, the tracer – or yourself, if you’re clumsy enough to be caught in its path. (Atari, 1981)

The Game: As the last of a race of spacefaring insects, you must defend yourself from a relentless wave of alien attackers bent on ridding the universe of your race. An alien tracer, deadly to the touch, tracks your every move, though it cannot harm you while you’re in the neutral zone at the center of the screen. You must eat away at the aliens’ shield, which not only reduces their defenses, but builds your energy reserve so you can fire your own powerful weapon, which can wipe out the alien, the tracer – or yourself, if you’re clumsy enough to be caught in its path. (Atari, 1981)

Memories: One of the coolest games ever conceived for the Atari 2600, Yars’ Revenge was a brilliant arcade-style game. In fact, I’m amazed that it apparently never made it into coin-op form (like such games as Lode Runner and Pitfall!). In fact, Yars actually started out as an arcade port – though in the end, it differed significantly enough from its inspiration (Star Castle) that it was a whole new game.

Memories: One of the coolest games ever conceived for the Atari 2600, Yars’ Revenge was a brilliant arcade-style game. In fact, I’m amazed that it apparently never made it into coin-op form (like such games as Lode Runner and Pitfall!). In fact, Yars actually started out as an arcade port – though in the end, it differed significantly enough from its inspiration (Star Castle) that it was a whole new game.

Video Pinball

The Game: Pull the plunger back and fire the ball into play. The more bumpers it hits, the more points you rack up. But don’t let the ball leave the table – doing so three times ends the game. (Atari, 1981)

The Game: Pull the plunger back and fire the ball into play. The more bumpers it hits, the more points you rack up. But don’t let the ball leave the table – doing so three times ends the game. (Atari, 1981)

Memories: I’m just not a huge fan of video pinball simulations – see my review of Thunderball! for Odyssey2 if you have any doubts – but having tried out Atari’s Video Pinball, I can say that it’s more fun than Thunderball! Itself a home version of one of Atari’s late 70s arcade titles, Video Pinball offers some finer graphics than you’d expect from the early waves of VCS titles.

UFO!

The Game: As the pilot of a lone space cruiser, you must try to clear the spaceways of a swarm of pesky and relatively harmless drone UFOs, but the job isn’t easy. You can ram the alien ships with your ship’s shields, destroying them (but forcing your shields offline for a few precious seconds during which anything could collide with your unprotected ship and destroy you), or shoot them (which also forces your shields down for a recharge). To that screenful of bite-sized chunks o’ death, add an unpredictable Killer UFO that likes to pop in and shoot at you, and suddenly being an interstellar traffic cop ain’t so easy. (Magnavox, 1981)

The Game: As the pilot of a lone space cruiser, you must try to clear the spaceways of a swarm of pesky and relatively harmless drone UFOs, but the job isn’t easy. You can ram the alien ships with your ship’s shields, destroying them (but forcing your shields offline for a few precious seconds during which anything could collide with your unprotected ship and destroy you), or shoot them (which also forces your shields down for a recharge). To that screenful of bite-sized chunks o’ death, add an unpredictable Killer UFO that likes to pop in and shoot at you, and suddenly being an interstellar traffic cop ain’t so easy. (Magnavox, 1981)

Memories: UFO! was the first “Challenger Series” game, which usually denoted a game that was an interesting derivative of an existing arcade favorite, in this case the popular Atari game Asteroids.

Tennis

The Game: Is it Pong anthropomorphized, or is it tennis rehumanized? Two people dash back and fourth across a court, making every attempt to intercept the incoming ball and slap it back into their opponent’s side of the net. As with so many other things in life, he who drops the ball suffers severely. (Activision, 1981)

The Game: Is it Pong anthropomorphized, or is it tennis rehumanized? Two people dash back and fourth across a court, making every attempt to intercept the incoming ball and slap it back into their opponent’s side of the net. As with so many other things in life, he who drops the ball suffers severely. (Activision, 1981)

Memories: Doesn’t really matter how you dress it up: it’s all tennis. Only Activision‘s Tennis cartridge, programmed by Alan Miller, was the first time someone had tried to make the tennis players look like…well, tennis players, at least on the VCS. As one of the very first titles released by Activision, Tennis broke graphical ground, but kept game play simple, often simulating an existing sport or activity – the salad days of innovation with games like Pitfall! were still to come.

Star Strike

The Game: Flying low over an alien installation, you are the last hope for the planet Earth. When the alien space vehicle has Earth lined up in the sights of its launcher, the planet will be destroyed. Your mission is to blast alien defensive fighters and bomb their mothership into oblivion before that happens. (Mattel, 1981)

The Game: Flying low over an alien installation, you are the last hope for the planet Earth. When the alien space vehicle has Earth lined up in the sights of its launcher, the planet will be destroyed. Your mission is to blast alien defensive fighters and bomb their mothership into oblivion before that happens. (Mattel, 1981)

Memories: Star Strike was one of the games Mattel waved in everyone’s face to prove how superior the Intellivision was to its rival, the Atari 2600. But for its time, and considering that Atari’s biggest hits at this point were chunky home versions of  the distinctly 2-D Asteroids, Missile Command and Space Invaders, Star Strike‘s Star Wars-inspired 3-D animated trench was quite impressive. However, the game was notoriously difficult for those weaned on the excessive simplicity of the aforementioned arcade adaptations.

the distinctly 2-D Asteroids, Missile Command and Space Invaders, Star Strike‘s Star Wars-inspired 3-D animated trench was quite impressive. However, the game was notoriously difficult for those weaned on the excessive simplicity of the aforementioned arcade adaptations.

Space Battle

The Game: You command a mighty battleship with three squadrons of fighters at your disposal to fend off five alien attack fleets. You can manually dispatch your fighter squadrons, send them directly into battle, and recall them to defend your ship. When your fighters go into battle, you can assume control personally and engage in a dogfight with the agile enemy fighters, or you can let the computer fight your battles on autopilot (it’ll get the job done, but usually with an undesirable, if not unacceptable, rate of losses for your side). The game ends when your squadrons have eliminated all of the converging alien fleets, or when the aliens have made quick work of both your squadrons and your command ship. (Mattel Electronics, 1979)

The Game: You command a mighty battleship with three squadrons of fighters at your disposal to fend off five alien attack fleets. You can manually dispatch your fighter squadrons, send them directly into battle, and recall them to defend your ship. When your fighters go into battle, you can assume control personally and engage in a dogfight with the agile enemy fighters, or you can let the computer fight your battles on autopilot (it’ll get the job done, but usually with an undesirable, if not unacceptable, rate of losses for your side). The game ends when your squadrons have eliminated all of the converging alien fleets, or when the aliens have made quick work of both your squadrons and your command ship. (Mattel Electronics, 1979)

Memories: In 1979, Glen Larson’s TV space epic Battlestar Galactica was as hot a property as you could get on the small screen, with its movie-scale special effects (or at least, the show’s underbudgeted and overworked producers and special effects wizards hoped you thought the effects were movie-scale). Having watched rival toy maker Kenner score a major coup with the license to manufacture toys based on Star Wars, Mattel quickly stepped in to snag the rights for Battlestar Galactica. Short of whatever Star Wars sequel George Lucas turned out next, Galactica was as close as you could get to the next big thing.

Spacechase

The Game: Piloting a lone spaceship zipping over a planet’s surface in a low, fast orbit, your mission is to kick some evasive alien butt. Drawing a bead on the aliens is much harder than it looks, and they arrive in waves of four. Naturally, it seems like it’s much easier for them to target you… (Games By Apollo, 1981)

The Game: Piloting a lone spaceship zipping over a planet’s surface in a low, fast orbit, your mission is to kick some evasive alien butt. Drawing a bead on the aliens is much harder than it looks, and they arrive in waves of four. Naturally, it seems like it’s much easier for them to target you… (Games By Apollo, 1981)

Memories: Quite an improvement over Richardson, Texas-based Games By Apollo’s first game, the disastrously bad Skeet Shoot, Spacechase isn’t going to blow the doors down in the game originality department, but it wasn’t bad for the VCS at all. The scrolling planetscape beneath the player’s ship may look like an artist’s vague impression of some Arizona landscape, but with games like Defender struggling to get the side-scrolling thing right, it was quite an accomplishment.

Space Armada

The Game: You’re the pilot of a ground-based mobile weapons platform, and there are buttloads of alien meanies headed right for you. Your only defense is a trio of shields which are degraded by any weapons fire – yours or theirs – and a quick trigger finger. Occasionally a mothership zips across the top of the screen. When the screen is cleared of invaders, another wave – faster and more aggressive – appears. When the aliens manage to land on Earth…it’s all over. (Mattel, 1981)

The Game: You’re the pilot of a ground-based mobile weapons platform, and there are buttloads of alien meanies headed right for you. Your only defense is a trio of shields which are degraded by any weapons fire – yours or theirs – and a quick trigger finger. Occasionally a mothership zips across the top of the screen. When the screen is cleared of invaders, another wave – faster and more aggressive – appears. When the aliens manage to land on Earth…it’s all over. (Mattel, 1981)

Memories: Sound familiar? It should. This early entry in Mattel’s library of Intellivision games is, rather obviously, a not-very-thinly-disguised version of Space Invaders, the game whose home version had made the Atari 2600 a household name in the home video game biz.

Snafu

The Game: As one of four color-coded player icons on the screen, you begin the round at one edge of the rectangular playing field. Your icon leaves a solid wall behind it, tracing your path. You try to trap other players or computer-controlled

The Game: As one of four color-coded player icons on the screen, you begin the round at one edge of the rectangular playing field. Your icon leaves a solid wall behind it, tracing your path. You try to trap other players or computer-controlled  icons in your wake, while avoiding the solid walls tracing their icons and your own trail, which is just as deadly. (Mattel, 1981)

icons in your wake, while avoiding the solid walls tracing their icons and your own trail, which is just as deadly. (Mattel, 1981)

Memories: Look familiar? A year later, and this gem of simplicity undoubtedly would have been titled Tron Light  Cycles (and just for giggles, we’ve prepared a special keypad overlay to fit that theme. The light cycle sequence from the movie Tron (as well as the similar screen in the arcade game based on the movie) and the basic premise of Snafu are the same.

Cycles (and just for giggles, we’ve prepared a special keypad overlay to fit that theme. The light cycle sequence from the movie Tron (as well as the similar screen in the arcade game based on the movie) and the basic premise of Snafu are the same.

Skeet Shoot

The Game: Line up moving targets in your sights and blast ’em away. The more targets you hit, the more points you get. Simple enough, eh? Just don’t expect everything to travel in a straight line – and keep in mind that something like 80% of the time you won’t have a chance of hitting anything at all due to where you’re positioned. (Games By Apollo, 1981)

The Game: Line up moving targets in your sights and blast ’em away. The more targets you hit, the more points you get. Simple enough, eh? Just don’t expect everything to travel in a straight line – and keep in mind that something like 80% of the time you won’t have a chance of hitting anything at all due to where you’re positioned. (Games By Apollo, 1981)

Memories: The 1983–84 crash of the home video game industry has often been blamed on an unstoppable tsunami wave of lousy games being produced by companies that had never before shown an interest in the field. Some pundits point at Activision‘s defeat of an Atari lawsuit – which claimed that third-party games would be unfair competition, as they alleged Activision‘s four principal programmers were using Atari trade secrets – as the first crack in the dam. And maybe they’re right. But at first, with Activision and Imagic releasing well-programmed, colorful, cutting edge and most of all fun games, it was all good – and Atari was still selling hardware, so how could they prove they’d lose out on the deal?

Pinball

The Game: It’s a game of video pinball where you can even bump the table to influence the ball’s path. You can even launch the ball into a second level to score big bonus points. Just don’t let it slide out of the reach of your flippers… (Mattel Electronics, 1981)

The Game: It’s a game of video pinball where you can even bump the table to influence the ball’s path. You can even launch the ball into a second level to score big bonus points. Just don’t let it slide out of the reach of your flippers… (Mattel Electronics, 1981)

Memories: As a rule, I don’t do the video pinball thing. You can look throughout Phosphor Dot Fossils and you’ll find very few big thumbs-up for video pinball. But so help me, Pinball on Intellivision is rather fun. It takes into account some of the physics (though far from all) involved in a pinball table, even the external factors such as the good old-fashioned, time-honored bump-the-machne maneuver.

Muncher

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Bally, 1981)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Bally, 1981)

Memories: 1981 was the year of Pac-Man fever, when everybody wanted to get the yellow gobbler on their console, or at least a reasonable facsimile thereof. Bally – having already tried to play fast and loose with licensing by releasing a dead-on accurate but unlicensed version of Galaxian under a different name – took another roll of the dice (appropriately for an outfit that also had a healthy stake in the casino business)…and lost.

Missile Command

The Game: Tucked away safely in an underground bunker, you are solely responsible for defending six cities from a relentless, ever-escalating ICBM attack. Your missile base is armed with three banks of nuclear missiles capable of intercepting the incoming enemy nukes, planes and smart bombs. One nuke hit on your base will incapacitate one bank of missiles for the rest of your current turn, but one nuke hit on any of your six cities will destroy it completely. (The only chance you have of rebuilding a city comes when a bonus city is awarded for every 10,000 points scored.) And when all six of your cities have been destroyed, the cataclysmic end of the world proceeds. Game over. (Atari, 1981)

The Game: Tucked away safely in an underground bunker, you are solely responsible for defending six cities from a relentless, ever-escalating ICBM attack. Your missile base is armed with three banks of nuclear missiles capable of intercepting the incoming enemy nukes, planes and smart bombs. One nuke hit on your base will incapacitate one bank of missiles for the rest of your current turn, but one nuke hit on any of your six cities will destroy it completely. (The only chance you have of rebuilding a city comes when a bonus city is awarded for every 10,000 points scored.) And when all six of your cities have been destroyed, the cataclysmic end of the world proceeds. Game over. (Atari, 1981)

Memories: After the runaway success of the licensed Space Invaders and its own in-house Asteroids translation, Atari started mining its own vaults for new cartridges – and Missile Command, the legendary Cold War video game that had given its designer nightmares about nuclear war, was a prime target.