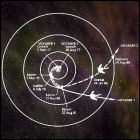

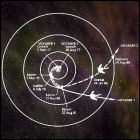

The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in 1961, Caltech/JPL grad student Gary Flandro has identified a favorable alignment of the outer planets which would allow for a single spacecraft to reach Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto within two decades. Vehicles taking advantage of this planetary alignment must lift off at very precise times during 1977 and 1978, and the alignment will not occur again for nearly 200 years. An ambitious plan is laid out for multiple flyby vehicles with atmospheric probes for every gas planet and landers for specific moons of interest, launched by Saturn V rockets. Budget realities scale this plan back: flybys will be carried out by two cheaper Mariner vehicles (later renamed Voyager), while the atmospheric and satellite probes – eventually to be renamed Galileo and Cassini – wait even longer to reach their destinations, and the Pluto flyby is scrapped until the 21st century New Horizons probe lifts off. JPL also recommends an inner solar system tryout of the gravitational assist maneuvers required, resulting in the Mariner 10 mission to Venus and Mercury.

The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in 1961, Caltech/JPL grad student Gary Flandro has identified a favorable alignment of the outer planets which would allow for a single spacecraft to reach Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto within two decades. Vehicles taking advantage of this planetary alignment must lift off at very precise times during 1977 and 1978, and the alignment will not occur again for nearly 200 years. An ambitious plan is laid out for multiple flyby vehicles with atmospheric probes for every gas planet and landers for specific moons of interest, launched by Saturn V rockets. Budget realities scale this plan back: flybys will be carried out by two cheaper Mariner vehicles (later renamed Voyager), while the atmospheric and satellite probes – eventually to be renamed Galileo and Cassini – wait even longer to reach their destinations, and the Pluto flyby is scrapped until the 21st century New Horizons probe lifts off. JPL also recommends an inner solar system tryout of the gravitational assist maneuvers required, resulting in the Mariner 10 mission to Venus and Mercury.

Using a telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, astronomer Seth Nicholson discovers Ananke, a tiny moon of Jupiter orbiting the huge planet at an average distance of 21 million miles and at a high inclination relative to Jupiter’s equator. Ananke is most likely a captured asteroid or the remnant of a captured asteroid, and other small Jovian moons in the same orbit may be other pieces of the captured (and shredded) body. Ananke is the first Jovian moon discovered in nearly two decades, and it will be over two more decades before another is found.

Using a telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, astronomer Seth Nicholson discovers Ananke, a tiny moon of Jupiter orbiting the huge planet at an average distance of 21 million miles and at a high inclination relative to Jupiter’s equator. Ananke is most likely a captured asteroid or the remnant of a captured asteroid, and other small Jovian moons in the same orbit may be other pieces of the captured (and shredded) body. Ananke is the first Jovian moon discovered in nearly two decades, and it will be over two more decades before another is found.

Recent Jet Propulsion Laboratory hire Michael Minovitch submits the first of a series of papers and technical memorandums on the possibility of using carefully-calculated gravitational assist maneuvers to speed transit time between celestial bodies while requiring minimal engine/fuel use. Where most previous scientific thought concentrated on using engine burns (and a lot of fuel) to cancel the effects of a planet’s gravity, Minovitch demonstrated that gravity could be a big help with a carefully calculated trajectory. Though nearly every planetary mission since then has capitalized on Minovitch’s research, it was initially rejected by JPL. Minovitch’s calculations are later revisited by Caltech grad student Gary Flandro, who flags down a particular combination of Minovitch’s pre-computed trajectories for a “grand tour” of the outer solar system, a mission which will eventually be known – in a somewhat scaled-down, less grand form – as Voyager.

Recent Jet Propulsion Laboratory hire Michael Minovitch submits the first of a series of papers and technical memorandums on the possibility of using carefully-calculated gravitational assist maneuvers to speed transit time between celestial bodies while requiring minimal engine/fuel use. Where most previous scientific thought concentrated on using engine burns (and a lot of fuel) to cancel the effects of a planet’s gravity, Minovitch demonstrated that gravity could be a big help with a carefully calculated trajectory. Though nearly every planetary mission since then has capitalized on Minovitch’s research, it was initially rejected by JPL. Minovitch’s calculations are later revisited by Caltech grad student Gary Flandro, who flags down a particular combination of Minovitch’s pre-computed trajectories for a “grand tour” of the outer solar system, a mission which will eventually be known – in a somewhat scaled-down, less grand form – as Voyager. The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in

The Grand Tour Outer Planets mission is proposed to NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Using a combination of the gravitational assist trajectories computed by JPL’s Michael Minovitch in  NASA launches Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft sent to study the huge planet Jupiter at close range. Its Atlas-Centaur booster gives it a good head start, propelling it to over 32,000 miles per hour en route to Jupiter, the fastest man-made object in history at this point. Pioneer 10 is also the first man-made vehicle to traverse the asteroid belt, with instruments detecting fewer large particles than anticipated. It will reach Jupiter in late

NASA launches Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft sent to study the huge planet Jupiter at close range. Its Atlas-Centaur booster gives it a good head start, propelling it to over 32,000 miles per hour en route to Jupiter, the fastest man-made object in history at this point. Pioneer 10 is also the first man-made vehicle to traverse the asteroid belt, with instruments detecting fewer large particles than anticipated. It will reach Jupiter in late  Having spent six years wrangling with various mission profiles for a “Grand Tour” of the outer solar system, made possible by a favorable planetary alignment occurring only once every 175 years, NASA finally authorizes a very stripped-down version of its original ambitious Grand Tour plans. The Mariner Jupiter/Saturn ’77 mission will consist of two twin unmanned spacecraft to be launched in

Having spent six years wrangling with various mission profiles for a “Grand Tour” of the outer solar system, made possible by a favorable planetary alignment occurring only once every 175 years, NASA finally authorizes a very stripped-down version of its original ambitious Grand Tour plans. The Mariner Jupiter/Saturn ’77 mission will consist of two twin unmanned spacecraft to be launched in  The unmanned space probe Pioneer 11 is launched on a course that will be one of the first real tests of the

The unmanned space probe Pioneer 11 is launched on a course that will be one of the first real tests of the  NASA’s Pioneer 10 space probe, launched in

NASA’s Pioneer 10 space probe, launched in  Astronomer Charles Kowal discovers Leda, a tiny, previously undiscovered moon of Jupiter, using Mount Palomar Observatory’s telescope. With a radius of less than seven miles and an inclined orbit, Leda is the first Jovian moon discovered in over two decades, and is among the last to be discovered using ground-based telescopes in the 20th century.

Astronomer Charles Kowal discovers Leda, a tiny, previously undiscovered moon of Jupiter, using Mount Palomar Observatory’s telescope. With a radius of less than seven miles and an inclined orbit, Leda is the first Jovian moon discovered in over two decades, and is among the last to be discovered using ground-based telescopes in the 20th century. NASA’s Pioneer 11 space probe passes close to Jupiter, barely 27,000 miles above the giant planet’s cloudtops, again encountering radiation capable of frying spacecraft electronics. Pioneer 11 captures the first images of Jupiter’s polar cloud structure and pulls off a daring gravity assist maneuver: the planet’s gravity flings Pioneer 11 up and over the north polar region and across the solar system for a

NASA’s Pioneer 11 space probe passes close to Jupiter, barely 27,000 miles above the giant planet’s cloudtops, again encountering radiation capable of frying spacecraft electronics. Pioneer 11 captures the first images of Jupiter’s polar cloud structure and pulls off a daring gravity assist maneuver: the planet’s gravity flings Pioneer 11 up and over the north polar region and across the solar system for a  Astronomers catch fleeting glimpses of a new natural satellite of Jupiter, Themisto, though the initial estimates of its orbit are “off” enough that Themisto becomes “lost” and isn’t observed again until 2000. With a diameter of roughly five miles, Themisto marks the dividing line between the larger inner moons of Jupiter and the widely-scattered menagerie of asteroid-like outer moons orbiting the planet. Astronomers Elizabeth Roemer and Charles Kowal (who discovered another new Jovian moon in 1974) share credit for discovering the moon. Themisto is the last Jovian satellite to be discovered by ground-based telescope in the 20th century.

Astronomers catch fleeting glimpses of a new natural satellite of Jupiter, Themisto, though the initial estimates of its orbit are “off” enough that Themisto becomes “lost” and isn’t observed again until 2000. With a diameter of roughly five miles, Themisto marks the dividing line between the larger inner moons of Jupiter and the widely-scattered menagerie of asteroid-like outer moons orbiting the planet. Astronomers Elizabeth Roemer and Charles Kowal (who discovered another new Jovian moon in 1974) share credit for discovering the moon. Themisto is the last Jovian satellite to be discovered by ground-based telescope in the 20th century. NASA Administrator James Fletcher announces that the ambitious twin Mariner Jupiter/Saturn ’77 space probes, due to be launched later in the year, have been christened with new names: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. The name change has been initiated by recently-promoted Voyager program manager John Casani, who thinks the spacecraft need a name that’s less of a mouthful (the name “Discoverer” was also considered). For the first time, NASA openly admits that one of the vehicles – Voyager 2 – may continue on to Uranus and Neptune should its Saturn flyby go well in 1981, depending on the spacecraft’s health.

NASA Administrator James Fletcher announces that the ambitious twin Mariner Jupiter/Saturn ’77 space probes, due to be launched later in the year, have been christened with new names: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. The name change has been initiated by recently-promoted Voyager program manager John Casani, who thinks the spacecraft need a name that’s less of a mouthful (the name “Discoverer” was also considered). For the first time, NASA openly admits that one of the vehicles – Voyager 2 – may continue on to Uranus and Neptune should its Saturn flyby go well in 1981, depending on the spacecraft’s health. Congress approves the largest NASA budget in ten years, including authorization and funding for two major unmanned spacecraft: a Space Telescope to be deployed into Earth orbit via Space Shuttle, and a yet-to-be-named Jupiter orbiter and atmospheric probe, originally proposed in the late 1960s as part of the outer planets Grand Tour mission plan. The Jupiter probe, which must be ready to launch in 1982 to take advantage of a planetary configuration providing the shortest distance between Earth and Jupiter, is the subject of a fierce budget fight in Congress. (This spacecraft will go on to be named Galileo.)

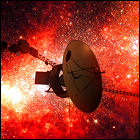

Congress approves the largest NASA budget in ten years, including authorization and funding for two major unmanned spacecraft: a Space Telescope to be deployed into Earth orbit via Space Shuttle, and a yet-to-be-named Jupiter orbiter and atmospheric probe, originally proposed in the late 1960s as part of the outer planets Grand Tour mission plan. The Jupiter probe, which must be ready to launch in 1982 to take advantage of a planetary configuration providing the shortest distance between Earth and Jupiter, is the subject of a fierce budget fight in Congress. (This spacecraft will go on to be named Galileo.) NASA launches Voyager 2 (weeks ahead of Voyager 1), giving the unmanned space probe the best shot of taking advantage of a favorable planetary alignment known as the “Grand Tour”. Using a series of carefully calculated gravity assists, Voyager has the potential to visit all four of the major outer gas planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – in under 15 years without having to expend fuel to make the trip. If Voyager 2 survives long enough to visit Uranus or Neptune, it will become the first man-made spacecraft to visit either planet.

NASA launches Voyager 2 (weeks ahead of Voyager 1), giving the unmanned space probe the best shot of taking advantage of a favorable planetary alignment known as the “Grand Tour”. Using a series of carefully calculated gravity assists, Voyager has the potential to visit all four of the major outer gas planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – in under 15 years without having to expend fuel to make the trip. If Voyager 2 survives long enough to visit Uranus or Neptune, it will become the first man-made spacecraft to visit either planet. The unmanned robotic

The unmanned robotic  NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe, en route to its first destination, develops a potentially mission-jeopardizing problem: the scan platform, which contains and aims many of Voyager’s scientific instruments, jams and becomes stuck in place. As Voyager 1 has yet to even reach Jupiter, this threatens to make it an expensive failure. Transmitting commands from Earth to give the scan platform a gentle three-axis workout, engineers at NASA manage to free the stuck instruments, salvaging Voyager 1’s mission to the outer planets and their moons. (A similar fault develops in Voyager 2 during its 1981 encounter with Saturn.)

NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe, en route to its first destination, develops a potentially mission-jeopardizing problem: the scan platform, which contains and aims many of Voyager’s scientific instruments, jams and becomes stuck in place. As Voyager 1 has yet to even reach Jupiter, this threatens to make it an expensive failure. Transmitting commands from Earth to give the scan platform a gentle three-axis workout, engineers at NASA manage to free the stuck instruments, salvaging Voyager 1’s mission to the outer planets and their moons. (A similar fault develops in Voyager 2 during its 1981 encounter with Saturn.) NASA’s Voyager 2 space probe, leaving the inner solar system en route to a grand tour of the outer planets, suddenly stops transmitting to Earth, failing to acknowledge commands sent by its ground controllers. Any chance of the probe conducting its studies of Jupiter and Saturn, let alone Uranus or Neptune, is in serious jeopardy. Discovering a problem with Voyager 2’s ability to compensate for the Doppler shift in signals coming from Earth, NASA engineers devise a workaround to compensate for this problem from the ground, saving the mission.

NASA’s Voyager 2 space probe, leaving the inner solar system en route to a grand tour of the outer planets, suddenly stops transmitting to Earth, failing to acknowledge commands sent by its ground controllers. Any chance of the probe conducting its studies of Jupiter and Saturn, let alone Uranus or Neptune, is in serious jeopardy. Discovering a problem with Voyager 2’s ability to compensate for the Doppler shift in signals coming from Earth, NASA engineers devise a workaround to compensate for this problem from the ground, saving the mission. Following a communications blackout scare in April 1978, JPL uploads an autonomous command sequence to the Voyager 2 unmanned space probe, which would allow the spacecraft to carry out a self-guided mission to Jupiter and Saturn, the results of which would automatically be transmitted to Earth even if Voyager 2 can receive no further instructions from Earth. Due to the command storage limitations of Voyager 2’s onboard computer, this automatic backup mission plan makes no allowances for pictures of Jupiter, saving that capability for Saturn instead. In the event that Voyager 2 can no longer hear commands from Earth, the extended mission to Uranus and Neptune would be forfeited in favor of “minimum science return” from Jupiter and Saturn.

Following a communications blackout scare in April 1978, JPL uploads an autonomous command sequence to the Voyager 2 unmanned space probe, which would allow the spacecraft to carry out a self-guided mission to Jupiter and Saturn, the results of which would automatically be transmitted to Earth even if Voyager 2 can receive no further instructions from Earth. Due to the command storage limitations of Voyager 2’s onboard computer, this automatic backup mission plan makes no allowances for pictures of Jupiter, saving that capability for Saturn instead. In the event that Voyager 2 can no longer hear commands from Earth, the extended mission to Uranus and Neptune would be forfeited in favor of “minimum science return” from Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 1 emerges unharmed from what is considered the outer limit of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, having entered this 223,000,000-mile-wide zone of space in December 1977. Voyager 2 is expected to emerge similarly unscathed in late October 1978. NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft had already demonstrated, in the early 1970s, that passage through the asteroid belt without mission-jeopardizing damage is possible. Both spacecraft are already imaging Jupiter from a distance of less than 180,000,000 miles, now meeting or exceeding the resolution of the best photos of Jupiter taken from Earth-based telescopes.

Voyager 1 emerges unharmed from what is considered the outer limit of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, having entered this 223,000,000-mile-wide zone of space in December 1977. Voyager 2 is expected to emerge similarly unscathed in late October 1978. NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft had already demonstrated, in the early 1970s, that passage through the asteroid belt without mission-jeopardizing damage is possible. Both spacecraft are already imaging Jupiter from a distance of less than 180,000,000 miles, now meeting or exceeding the resolution of the best photos of Jupiter taken from Earth-based telescopes. From a distance of 36 million miles, NASA/JPL’s unmanned spacecraft Voyager 1 can already see the planet Jupiter in far greater detail than the cameras aboard Pioneers 10 and 11. Over the next month, Voyager 1 records images as it closes in on its first planetary target, spotting roiling storm clouds and fluid cloud bands with unprecedented clarity; JPL assembles the images into a “movie.” Despite the size of Jupiter at the end of the sequence, Voyager 1 is still over a month away from its closest pass to the giant planet.

From a distance of 36 million miles, NASA/JPL’s unmanned spacecraft Voyager 1 can already see the planet Jupiter in far greater detail than the cameras aboard Pioneers 10 and 11. Over the next month, Voyager 1 records images as it closes in on its first planetary target, spotting roiling storm clouds and fluid cloud bands with unprecedented clarity; JPL assembles the images into a “movie.” Despite the size of Jupiter at the end of the sequence, Voyager 1 is still over a month away from its closest pass to the giant planet. As it nears its closest approach to the planet Jupiter, NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe detects the first likely signs of a ring system around Jupiter’s equatorial region. Barely visible until Voyager 1 is behind the planet and can see them through scattered sunlight, the rings are only about 20 miles thick, but are over 150,000 miles in diameter. The lead time between Voyager 1’s visit and Voyager 2’s later flyby allows ground controllers to plan a better observation campaign for Voyager 1’s sister ship, and the rings are observed in more detail by the later Galileo and New Horizons missions.

As it nears its closest approach to the planet Jupiter, NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe detects the first likely signs of a ring system around Jupiter’s equatorial region. Barely visible until Voyager 1 is behind the planet and can see them through scattered sunlight, the rings are only about 20 miles thick, but are over 150,000 miles in diameter. The lead time between Voyager 1’s visit and Voyager 2’s later flyby allows ground controllers to plan a better observation campaign for Voyager 1’s sister ship, and the rings are observed in more detail by the later Galileo and New Horizons missions. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Voyager 1 makes its closest approach to the giant planet Jupiter, a little over 200,000 miles away. While Voyager’s higher-resolution cameras trump any of the Pioneer images of Jupiter, the real revelation proves to be Jupiter’s four largest moons, revealing a smooth-but-cracked icy surface on Europa, craters on Ganymede and Callisto, and the colorful mountains of Io, whose biggest secret goes undiscovered until a few days after Voyager 1’s closest flyby.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Voyager 1 makes its closest approach to the giant planet Jupiter, a little over 200,000 miles away. While Voyager’s higher-resolution cameras trump any of the Pioneer images of Jupiter, the real revelation proves to be Jupiter’s four largest moons, revealing a smooth-but-cracked icy surface on Europa, craters on Ganymede and Callisto, and the colorful mountains of Io, whose biggest secret goes undiscovered until a few days after Voyager 1’s closest flyby. JPL navigation engineer Linda Morabito, double-checking raw Voyager 1 images to ensure that the unmanned space probe is properly aligned for its encounter with Saturn in 1980, discovers the first evidence of active volcanoes on another body in Earth’s solar system: a plume of sulfur erupting over 150 feet above the surface of Jupiter’s moon Io. Scientists rush to check Voyager 1’s other Io images, and find that Voyager’s cameras caught more than half a dozen eruptions in the act.

JPL navigation engineer Linda Morabito, double-checking raw Voyager 1 images to ensure that the unmanned space probe is properly aligned for its encounter with Saturn in 1980, discovers the first evidence of active volcanoes on another body in Earth’s solar system: a plume of sulfur erupting over 150 feet above the surface of Jupiter’s moon Io. Scientists rush to check Voyager 1’s other Io images, and find that Voyager’s cameras caught more than half a dozen eruptions in the act. Tiny Adrastea, a small, asteroid-like moon of Jupiter, is discovered in photos returned by Voyager 2 during its flyby of the planet. Adrastea orbits along the outer edge of Jupiter’s ring system, and is likely to be the body from which material for that ring is ejected. Its close orbit carries it around the planet at a speed faster than Jupiter’s rotation, one of the few bodies in the solar system locked into such a fast orbit.

Tiny Adrastea, a small, asteroid-like moon of Jupiter, is discovered in photos returned by Voyager 2 during its flyby of the planet. Adrastea orbits along the outer edge of Jupiter’s ring system, and is likely to be the body from which material for that ring is ejected. Its close orbit carries it around the planet at a speed faster than Jupiter’s rotation, one of the few bodies in the solar system locked into such a fast orbit. Space Shuttle Atlantis lifts off on a mission lasting nearly five days, whose primary goal is to lift the interplanetary probe Galileo into orbit. Originally intended for launch in late 1982, Galileo is bound for Jupiter by way of a

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifts off on a mission lasting nearly five days, whose primary goal is to lift the interplanetary probe Galileo into orbit. Originally intended for launch in late 1982, Galileo is bound for Jupiter by way of a  Launched in 1989 via Space Shuttle, the unmanned Galileo probe reveals a significant technical problem during its first flyby of Earth: the umbrella-like high-gain antenna, allowing it to send its observations of Jupiter and its moons back to Earth at high speed, is stuck in a partly-open, partly-closed configuration that prevents its use. Ground engineers at JPL have to devise data compression schemes, and a tight record/playback schedule, that will allow Galileo to take all of its planned observations and send them back to Earth at a lower bit rate than planned. It is theorized that the long delays in Galileo’s launch – the probe was ready for launch in 1982 but had to wait through delays in the early shuttle program and was then kept in storage in the aftermath of the Challenger disaster – allowed the antenna’s lubricant to dry up. Galileo won’t reach its target planet, Jupiter, until 1995.

Launched in 1989 via Space Shuttle, the unmanned Galileo probe reveals a significant technical problem during its first flyby of Earth: the umbrella-like high-gain antenna, allowing it to send its observations of Jupiter and its moons back to Earth at high speed, is stuck in a partly-open, partly-closed configuration that prevents its use. Ground engineers at JPL have to devise data compression schemes, and a tight record/playback schedule, that will allow Galileo to take all of its planned observations and send them back to Earth at a lower bit rate than planned. It is theorized that the long delays in Galileo’s launch – the probe was ready for launch in 1982 but had to wait through delays in the early shuttle program and was then kept in storage in the aftermath of the Challenger disaster – allowed the antenna’s lubricant to dry up. Galileo won’t reach its target planet, Jupiter, until 1995. Astronomers on Earth discover a comet like none seen before: having flown close to Jupiter in July 1992, the comet has broken into multiple pieces in a configuration that its discoverers call “a string of pearls.” Calculations of the orbit of the newly detected comet, named Shoemaker-Levy 9 after the team that discovered it, reveal something stunning: the orbit of the fragments will bring them back to Jupiter in just over a year, at which point they are expected to collide with the planet rather than pass it by or go into orbit. Not only does this give Earth-based astronomers time to coordinate observations, but NASA has an ace in the hole: the entire event will be witnessed by the unmanned Galileo probe as it makes its final approach to the giant planet.

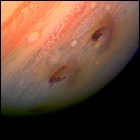

Astronomers on Earth discover a comet like none seen before: having flown close to Jupiter in July 1992, the comet has broken into multiple pieces in a configuration that its discoverers call “a string of pearls.” Calculations of the orbit of the newly detected comet, named Shoemaker-Levy 9 after the team that discovered it, reveal something stunning: the orbit of the fragments will bring them back to Jupiter in just over a year, at which point they are expected to collide with the planet rather than pass it by or go into orbit. Not only does this give Earth-based astronomers time to coordinate observations, but NASA has an ace in the hole: the entire event will be witnessed by the unmanned Galileo probe as it makes its final approach to the giant planet. Its collision with the solar system’s largest planet predicted over a year in advance, the fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 begin impacting Jupiter’s atmosphere in an astronomical event lasting six days. With Earth-based telescopes watching, as well as cameras and instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope, Galileo and even Voyager 2, huge explosions are witnessed as the cometary chunks slam into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere at over 200,000 miles per hour, leaving dark “scars” larger than the diameter of Earth visible on the planet’s atmosphere and releasing more heat than the surface of the sun. Galileo is still over a year away from arriving at Jupiter.

Its collision with the solar system’s largest planet predicted over a year in advance, the fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 begin impacting Jupiter’s atmosphere in an astronomical event lasting six days. With Earth-based telescopes watching, as well as cameras and instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope, Galileo and even Voyager 2, huge explosions are witnessed as the cometary chunks slam into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere at over 200,000 miles per hour, leaving dark “scars” larger than the diameter of Earth visible on the planet’s atmosphere and releasing more heat than the surface of the sun. Galileo is still over a year away from arriving at Jupiter. After five months of independent flight, the Galileo atmospheric probe slams into the atmosphere of giant planet Jupiter at a speed over 100,000mph, burrowing over a hundred miles into the huge planet’s dense atmosphere before the heat of entry and the atmospheric pressure crush the probe. Deploying a parachute to slow its descent, the probe survives for nearly an hour, its sensors finding a surprisingly dry atmosphere. As it plummets toward the center of Jupiter, the Galileo probe registers 450mph winds, but never finds any hints of anything resembling a solid surface. The sum total of the probe’s sensor readings – the entirety of our data gathered directly within the atmosphere of Jupiter – tops out at 460 kilobytes of data.

After five months of independent flight, the Galileo atmospheric probe slams into the atmosphere of giant planet Jupiter at a speed over 100,000mph, burrowing over a hundred miles into the huge planet’s dense atmosphere before the heat of entry and the atmospheric pressure crush the probe. Deploying a parachute to slow its descent, the probe survives for nearly an hour, its sensors finding a surprisingly dry atmosphere. As it plummets toward the center of Jupiter, the Galileo probe registers 450mph winds, but never finds any hints of anything resembling a solid surface. The sum total of the probe’s sensor readings – the entirety of our data gathered directly within the atmosphere of Jupiter – tops out at 460 kilobytes of data. Beating the odds imposed upon it by the unforgiving environment around the planet Jupiter and its major moons, and engineering challenges such as a high-gain antenna that never unfurled properly after its 1989 launch, NASA’s Galileo space probe completes its two-year mission. Since the spacecraft is still intact and reasonably healthy, NASA gains a two-year extension, which it calls the Galileo Europa Mission, focusing on the two innermost large moons, icy Europa and volcanic Io. Trajectories are planned to fly Galileo even closer to these moons than ever before, though the harsh radiation zone around Jupiter itself could fry Galileo’s main computer and end the mission at any time.

Beating the odds imposed upon it by the unforgiving environment around the planet Jupiter and its major moons, and engineering challenges such as a high-gain antenna that never unfurled properly after its 1989 launch, NASA’s Galileo space probe completes its two-year mission. Since the spacecraft is still intact and reasonably healthy, NASA gains a two-year extension, which it calls the Galileo Europa Mission, focusing on the two innermost large moons, icy Europa and volcanic Io. Trajectories are planned to fly Galileo even closer to these moons than ever before, though the harsh radiation zone around Jupiter itself could fry Galileo’s main computer and end the mission at any time. The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Galileo makes a remarkable find at Callisto, the outermost of Jupiter’s four large “Galilean” moons: evidence that a saltwater ocean may lie beneath the moon’s pockmarked surface. Even more unusually, it may be the catalyst for Callisto’s magnetic field (a rarity for a satellite – not even all of the solar system’s planets have magnetic fields). Galileo’s instruments raise the possibility that the subsurface ocean may be conducting electricity and helping to generate that field (which current scientific models say Callisto should be too small to generate on its own). Scientists do not, however, believe that Callisto is a strong candidate to support life, unlike Europa.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Galileo makes a remarkable find at Callisto, the outermost of Jupiter’s four large “Galilean” moons: evidence that a saltwater ocean may lie beneath the moon’s pockmarked surface. Even more unusually, it may be the catalyst for Callisto’s magnetic field (a rarity for a satellite – not even all of the solar system’s planets have magnetic fields). Galileo’s instruments raise the possibility that the subsurface ocean may be conducting electricity and helping to generate that field (which current scientific models say Callisto should be too small to generate on its own). Scientists do not, however, believe that Callisto is a strong candidate to support life, unlike Europa.