In the beginning, home video games were at a bit of a crossroads – everyone wanted to play their favorite games at home, but parents didn’t want to tie up the only TV in the house. (This, of course, being back in the day when there was only one TV in the average American household.) The solution seemed simple: battery-powered electronic handheld games became a big hit. Though they used the same basic operating principles as their video game counterparts, and in some cases the same processors, the handheld games often relied on LEDs or matrices of pre-drawn, fixed character shapes. Often, this meant those graphics might be fancier than those that could be achieved by, say, the Atari 2600, but there was little or no fluidity to those graphics. In some games, such as

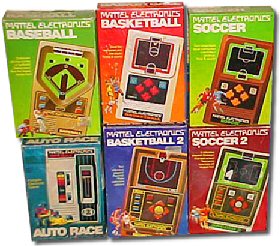

In the beginning, home video games were at a bit of a crossroads – everyone wanted to play their favorite games at home, but parents didn’t want to tie up the only TV in the house. (This, of course, being back in the day when there was only one TV in the average American household.) The solution seemed simple: battery-powered electronic handheld games became a big hit. Though they used the same basic operating principles as their video game counterparts, and in some cases the same processors, the handheld games often relied on LEDs or matrices of pre-drawn, fixed character shapes. Often, this meant those graphics might be fancier than those that could be achieved by, say, the Atari 2600, but there was little or no fluidity to those graphics. In some games, such as  Merlin or Mattel’s enduringly popular Electronic Football, there were no “characters” at all to speak of, only grids of tiny light-emitting diodes.

Merlin or Mattel’s enduringly popular Electronic Football, there were no “characters” at all to speak of, only grids of tiny light-emitting diodes.

Often, these games were retired as the novelty wore off, but the basic concept endured through endless permutations. Nintendo’s liquid-crystal display Game & Watch series not only  brought Donkey Kong and other Nintendo games to the pockets of schoolchildren everywhere, but they introduced the “plus pad” control configuration that Nintendo still uses on the GameCube and other platforms. Coleco turned the same basic shape into a series of immensely popular – and somewhat pricey – “mini-arcade” versions of licensed games. And Milton-Bradley seized on a revolutionary idea of introducing interchangeable cartridges to handheld games with

brought Donkey Kong and other Nintendo games to the pockets of schoolchildren everywhere, but they introduced the “plus pad” control configuration that Nintendo still uses on the GameCube and other platforms. Coleco turned the same basic shape into a series of immensely popular – and somewhat pricey – “mini-arcade” versions of licensed games. And Milton-Bradley seized on a revolutionary idea of introducing interchangeable cartridges to handheld games with  their LCD-based Microvision system.

their LCD-based Microvision system.

This was classic gaming without the TV. Whether they fit in our pockets or not, handhelds made their mark – and in 1989, when Nintendo revived the same basic concept as the Microvision, gave it a higher-resolution LCD display and crisp stereo sound, and called it the Game Boy, handhelds developed into their own critical niche of the video game industry.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=399,435]