Atari 2600 Video Computer System

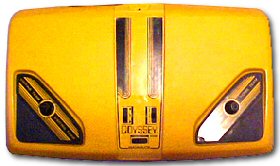

Chances are, if you were like most people and had a home video game in the late 70s or early 80s, it was an Atari 2600 (also repackaged by Sears as the “Sears Tele-Games” console). The Odyssey 2 was just a bit too esoteric for most people, and Mattel’s Intellivision suffered from that general perception as well. Colecovision was a very high-priced luxury game, and the Atari 5200 would’ve meant an expensive upgrade to a machine that couldn’t play the Atari 2600 games (Coleco got an Atari adapter on the market long before Atari itself furnished one for the 5200 – ironically, 2600 compatibility was a pivot point for sales of the next generation of consoles).

Chances are, if you were like most people and had a home video game in the late 70s or early 80s, it was an Atari 2600 (also repackaged by Sears as the “Sears Tele-Games” console). The Odyssey 2 was just a bit too esoteric for most people, and Mattel’s Intellivision suffered from that general perception as well. Colecovision was a very high-priced luxury game, and the Atari 5200 would’ve meant an expensive upgrade to a machine that couldn’t play the Atari 2600 games (Coleco got an Atari adapter on the market long before Atari itself furnished one for the 5200 – ironically, 2600 compatibility was a pivot point for sales of the next generation of consoles).

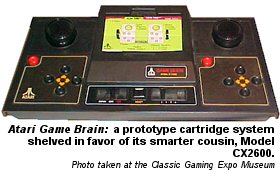

The Atari 2600, known early on as the Atari VCS (Video Computer System), was Atari’s second shot at a cartridge-based system. The company’s R&D department had been working on a machine called Game Brain which would have been the exact opposite of the original Magnavox Odyssey: Game Brain cartridges would have contained all of the computing power for their four built-in games per cartridge; the main unit itself had very little inside it, simply passing the video and audio generated by the cartridges on to the TV screen. Ultimately, it was little better than Atari’s dedicated Pong and Stunt Cycle consoles, and it was set aside in favor of a truly programmable system.

The Atari 2600, known early on as the Atari VCS (Video Computer System), was Atari’s second shot at a cartridge-based system. The company’s R&D department had been working on a machine called Game Brain which would have been the exact opposite of the original Magnavox Odyssey: Game Brain cartridges would have contained all of the computing power for their four built-in games per cartridge; the main unit itself had very little inside it, simply passing the video and audio generated by the cartridges on to the TV screen. Ultimately, it was little better than Atari’s dedicated Pong and Stunt Cycle consoles, and it was set aside in favor of a truly programmable system.

Ironically, while some people later blamed Atari – and specifically CEO Ray Kassar – for keeping the 2600 on the market too long (its last new mass-production game was released in 1990), the machine almost died an early death under Atari’s founder, Nolan Bushnell. He wanted to move on and start developing the next generation of game hardware, but Kassar, representing Atari’s new corporate parent company Warner Communications, had other ideas. A deal was sealed to license Space Invaders, the first-ever arcade title licensed by another company for home translation, sales skyrocketed, and the 2600 was here to stay.

Ironically, while some people later blamed Atari – and specifically CEO Ray Kassar – for keeping the 2600 on the market too long (its last new mass-production game was released in 1990), the machine almost died an early death under Atari’s founder, Nolan Bushnell. He wanted to move on and start developing the next generation of game hardware, but Kassar, representing Atari’s new corporate parent company Warner Communications, had other ideas. A deal was sealed to license Space Invaders, the first-ever arcade title licensed by another company for home translation, sales skyrocketed, and the 2600 was here to stay.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=14,24,44]

Rogues’ gallery of controllers. Seen here are just a few of the many joysticks and other specialized controllers manufactured for the Atari 2600 by Atari itself and several other companies. The standard Atari CX40 joystick is nearly an icon unto itself, while arcade control maker Wico got in on the act with its Command Control series including an arcade-style joystick and trakball. For young hands too small to handle Wico’s massive joystick (which, at the time, meant mine), Suncom made the very cool and responsive Slik Stik. Other controllers were specific to just one game or a handful of them – and you’ll find them elsewhere in this archive as well.

Rogues’ gallery of controllers. Seen here are just a few of the many joysticks and other specialized controllers manufactured for the Atari 2600 by Atari itself and several other companies. The standard Atari CX40 joystick is nearly an icon unto itself, while arcade control maker Wico got in on the act with its Command Control series including an arcade-style joystick and trakball. For young hands too small to handle Wico’s massive joystick (which, at the time, meant mine), Suncom made the very cool and responsive Slik Stik. Other controllers were specific to just one game or a handful of them – and you’ll find them elsewhere in this archive as well.

Bally Professional Arcade / Astrocade

Introduced as two types of products prepared to take over the world – personal computers and home video game consoles – the Bally Professional Arcade tried very hard to be both at the same time…and maybe that’s why it didn’t catch on like wildfire.

Introduced as two types of products prepared to take over the world – personal computers and home video game consoles – the Bally Professional Arcade tried very hard to be both at the same time…and maybe that’s why it didn’t catch on like wildfire.

On the surface, a home game machine by Bally – who, via its Midway division, already had a strong pedigree in the arcade – would seem like a shoo-in. (Midway’s greatest successes – licensing Japanese titles such as Pac-Man – were still in the future, however.) The Professional Arcade counted among its lead designers one Jay Fenton, who would later go on to create Gorf (and who would later become Jamie Fenton), and featured unique controllers and unique games. Though one might think that Bally would’ve had the first right of refusal on Midway’s games, most of those games made their way to the Professional Arcade under different names rather than as fully licensed titles. The Professional Arcade boasted some of the best arcade ports of its day, but when the games’ names didn’t match up with their arcade counterparts, few seemed to notice.

One feature that was unique to the Bally Professional Arcade for a long time was the Bally BASIC cartridge, allowing players to create their own programs and simple games. With the ability to save the resulting programs to cassette, there was an underground market for user-created software, certainly the first time that a home video game’s user base even had that option. This also kept Professional Arcade users satiated when Bally somewhat surprisingly bowed out of the home video game race, surrendering to console heavyweights like Atari so it could instead concentrate on Midway’s arcade games and Bally’s line of casino games.

The Bally Professional Arcade later resurfaced under the name “Astrocade”, slightly repackaged and boasting some new software; as with Fairchild’s Channel F, the Professional Arcade was bought by an outside company that wanted to gamble on getting into the video game market. Astrocade wasn’t on the map for long, though – this new generation of the Bally Professional Arcade was around just long enough for the industry to crash, taking Astrocade and nearly everyone else out with it.

There was still a demand for user-created software, and even now homebrew game programmers are rediscovering the Professional Arcade.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=257]

Special thanks to Kevin Moon for the Bally Professional Arcade photo.

Apple II

This, they said, was the computer that would conquer the world.

This, they said, was the computer that would conquer the world.

But it didn’t, did it? If it had, you might be viewing this page on a mega-advanced variant of the mighty Apple II series of computers.

Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer in the 1970s with the creation of the Apple I, a Heathkit-style, build-it-yourself computer kit. The sales were so promising on the Apple I that the two, with the help from some marketing geniuses of the day, stepped up to a mass-produced, ready-to-use unit called the Apple II. Armed with a cassette data storage device, a couple of small game paddles, and an RF modulator to hook it up to users’ TV sets, the Apple II took off. The beauty of the Apple II’s architecture was its expandibility. When the Apple II+ arrived, there was a disk drive, a dedicated monitor, 48k of RAM (impressive for a home computer around 1980), and third party software publishers were making it a viable platform. Not long after, the Apple IIe hit the market, with 64k of RAM and even more software. The Apple IIc – a heavy all-in-one unit with a built-in floppy drive, 128k of RAM, and a suitcase-style handle – was touted as a portable computer for business, and in 1984, the Apple IIGS appeared, completely changing the structure and offering unbelievable graphics and sound for a home computer at that time. Sadly, around 1984, two other machines yanked the carpet out from under the feet of the Apple II series – IBM’s increasingly prolific PCs, and Apple’s own Macintosh.

The Apple II computers may seem out-of-place in a retrospective about video games, but I feel compelled to make that exception. The Apple II was my first computer (well, actually, the Franklin ACE 1000, a clone machine that landed Franklin Computers on the losing end of an Apple copyright infringement lawsuit, was my first computer). It not only allowed me to play the games I already loved, such as Zaxxon and Robotron: 2084, but it introduced me to more sophisticated games that my beloved old Atari 2600 and Odyssey 2 consoles would never have been able to handle. Strategic games, simulations, and more. And I could also now program my own games on the Apple II, and I did so quite frequently – or at least I tried to!It was a cool machine.

![]() When I got that 300 baud modem in 1983, I remember thinking how cool it would be to program a game that two people could play, “live.” And I tried to program it myself, but no other kids at school had an Apple II, so I gave up on it for the time being, instead getting into the world of online Bulletin Board Systems…in other words, the Apple II is responsible for this site’s existence. The original LogBook episode guides were written in an Apple II text editor.

When I got that 300 baud modem in 1983, I remember thinking how cool it would be to program a game that two people could play, “live.” And I tried to program it myself, but no other kids at school had an Apple II, so I gave up on it for the time being, instead getting into the world of online Bulletin Board Systems…in other words, the Apple II is responsible for this site’s existence. The original LogBook episode guides were written in an Apple II text editor.

This section of Phosphor Dot Fossils will take you back to an earlier age when game play was still the key element…but real computer power, all 128 whopping kilobytes of it, meant that the game play could be much more interesting than ever before.

[wpucv_list id=”3145″ title=”Classic list with thumbs 1″]

Did you know that the author of Phosphor Dot Fossils once wrote his own (unreleased) game for the Apple II? Find out more about Intergalactic Trade: Mark II here.

Baseball

The Game: It’s a day at the digital ballpark for two players; the game is very simple – players control the timing of pitches and batting, which will determine how the game unfolds. The highest score at the end of nine innings wins. (RCA, 1977)

The Game: It’s a day at the digital ballpark for two players; the game is very simple – players control the timing of pitches and batting, which will determine how the game unfolds. The highest score at the end of nine innings wins. (RCA, 1977)

Memories: I’m all for a simple game of video baseball. When it got to the point that baseball video games were keeping track of batting averages and other stats, that knocked the genre out of the park for me – I was more than happy to stick to baseball on the Odyssey2 and the Game Boy (the two best video versions of the sport for my money). However, it is possible – even for someone with simple tastes like mine – to go too far in the opposite direction: too basic. RCA’s Baseball for the Studio II goes over that line.

Checkmate

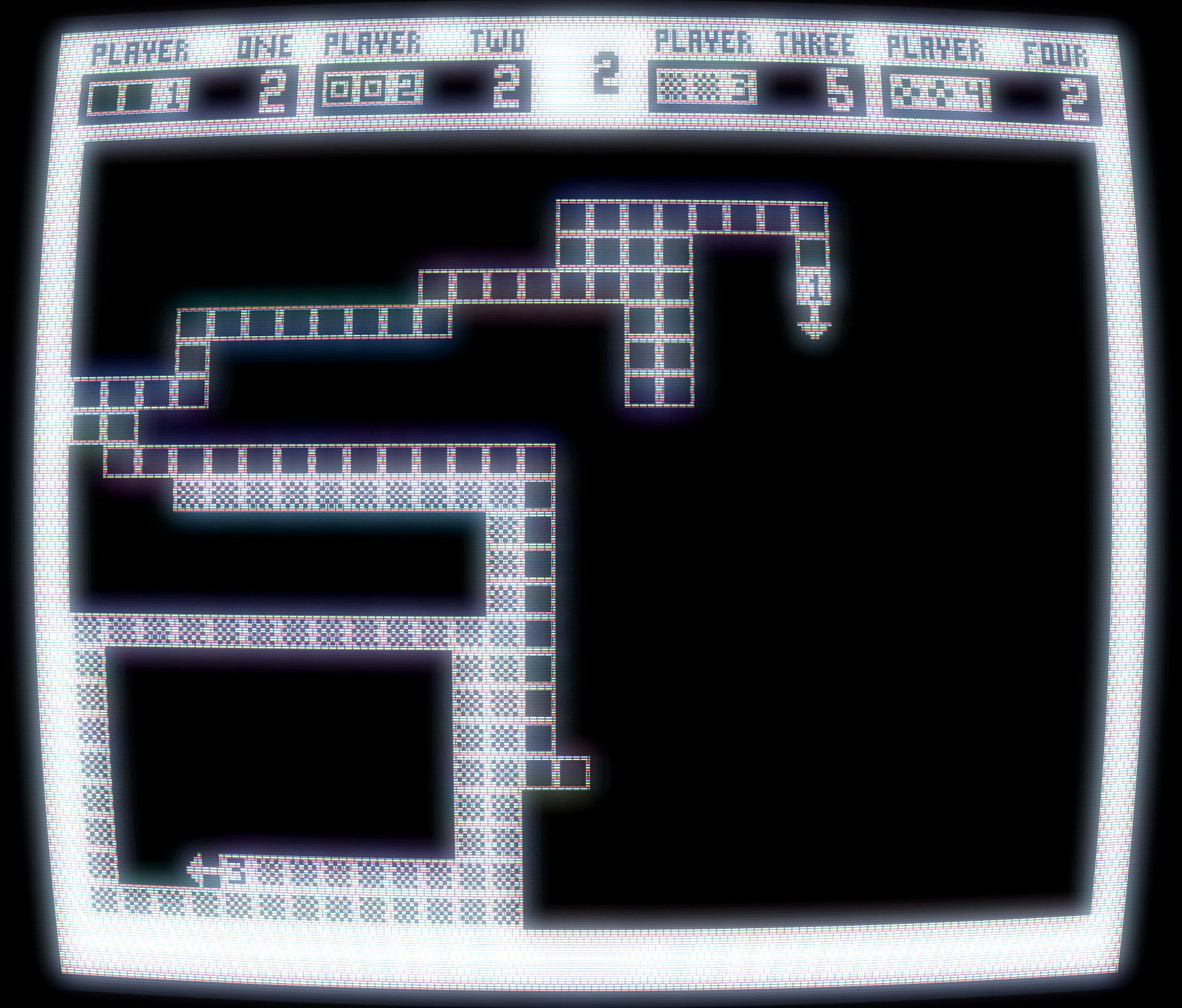

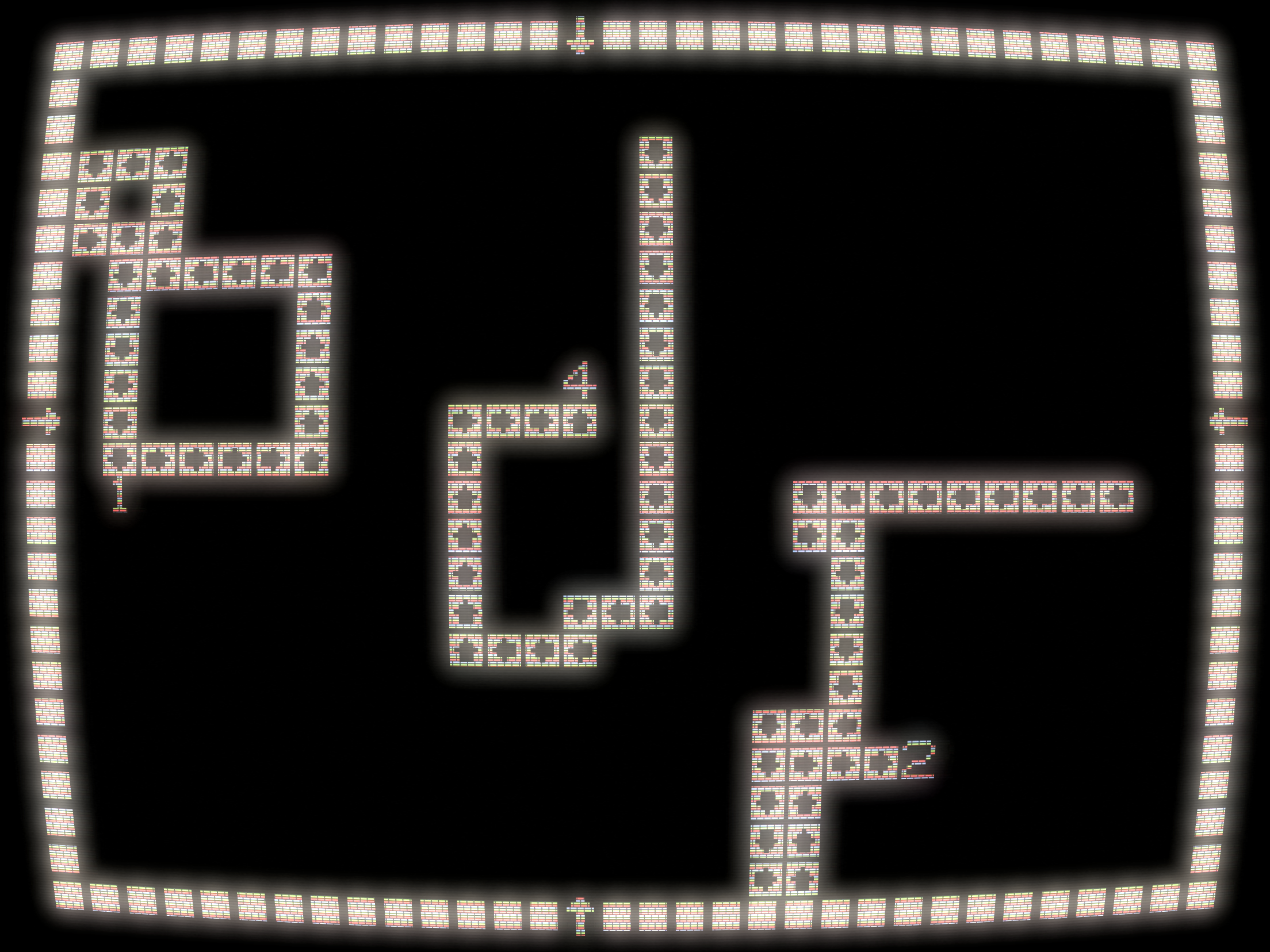

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Midway, 1977)

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Midway, 1977)

Memories: Any classic gamer worth his weight in pixels will recognize Checkmate as one of the inspirations for the Light Cycle sequence in both the movie and the game adaptation of Tron – but that doesn’t mean that Tron had to be behind the wheel for this concept to be a lot of fun.

RCA Studio II

Rolled out in 1977 alongside other early cartridge-based systems as the Fairchild Channel F and Atari VCS, RCA’s Studio II heralded the entry of a TV/technology giant into the burgeoning video game landscape. To put it in context, RCA was a significant entity in American television and electronics in the 1970s: this was kind of like Sony deciding to launch a video game console. Only about ten years before, RCA had launched its first color television sets on the American market, and at the time, it also owned NBC. RCA funneled money into NBC’s coffers to ensure a flow of color (and colorful) programming to make the switch to color television an enticing one for the public, keeping such shows as Star Trek alive when ratings alone would’ve dictated swift cancellation. To put it succinctly, in the age before Japanese-made electronics dominated the market, RCA wielded a big stick. Surely, if RCA was wading into the video game market, it was going to be something major.

Rolled out in 1977 alongside other early cartridge-based systems as the Fairchild Channel F and Atari VCS, RCA’s Studio II heralded the entry of a TV/technology giant into the burgeoning video game landscape. To put it in context, RCA was a significant entity in American television and electronics in the 1970s: this was kind of like Sony deciding to launch a video game console. Only about ten years before, RCA had launched its first color television sets on the American market, and at the time, it also owned NBC. RCA funneled money into NBC’s coffers to ensure a flow of color (and colorful) programming to make the switch to color television an enticing one for the public, keeping such shows as Star Trek alive when ratings alone would’ve dictated swift cancellation. To put it succinctly, in the age before Japanese-made electronics dominated the market, RCA wielded a big stick. Surely, if RCA was wading into the video game market, it was going to be something major.

There’s just one problem: RCA misjudged its first video game console by a wide margin. Whether it was a development curve that failed to take the latest developments into account, or whether it was a complete misunderstanding of the market, the Studio II “home television programmer” seemed like a game machine that arrived late to the party. Its black & white graphics already marked it as a relic; Atari, Coleco and Magnavox had made the move to color with their respective Pong, Telstar and Odyssey lines already. Aside from not making the leap to color (a surprising move from a company that had used all of its influence to shoehorn color TV into the American living room a decade earlier), the graphics were barely graphics at all: big, blocky and clumsy. Control of the Studio II was achieved using two twelve-key keypads that couldn’t be removed from the base unit, forcing players to be virtually glued to the machine…which couldn’t be placed very far from the TV.

To put it mildly, most consumers probably expected much better from RCA, and Studio II’s disappointing sales reflected this. Barely a dozen games hit the market before RCA declared the project dead and left the video game market for good. Ironically, though, the processor at  the heart of the Studio II would find a niche in the world of space exploration. After Pioneers 10 and 11 swung past Jupiter in the early 1970s, nearly getting their electronic brains fried by the huge planet’s intense radiation, NASA was in the market for a radiation-resistant chip – and the COSMAC chip which drove the Studio II quickly became the chip of choice for spacecraft venturing into unfriendly environments. Radiation-hardened versions of the COSMAC chip used by Studio II flew on Voyagers 1 and 2 (which were also launched in 1977) and Galileo; given the spectacular results achieved by those robotic explorers, one has to imagine that their COSMAC chips were uprated versions as well…because their pictures of Jupiter didn’t look like they came out of a RCA Studio II.

the heart of the Studio II would find a niche in the world of space exploration. After Pioneers 10 and 11 swung past Jupiter in the early 1970s, nearly getting their electronic brains fried by the huge planet’s intense radiation, NASA was in the market for a radiation-resistant chip – and the COSMAC chip which drove the Studio II quickly became the chip of choice for spacecraft venturing into unfriendly environments. Radiation-hardened versions of the COSMAC chip used by Studio II flew on Voyagers 1 and 2 (which were also launched in 1977) and Galileo; given the spectacular results achieved by those robotic explorers, one has to imagine that their COSMAC chips were uprated versions as well…because their pictures of Jupiter didn’t look like they came out of a RCA Studio II.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=446]

Fairchild Channel F

It goes without saying that video games were big business in the 1970s, but sometimes getting a look at the players attempting to make their name on that particular field is a good indicator of just how big the business was. Take Fairchild Semiconductor, for example – a well-known player in the integrated circuit business already, Fairchild dipped its toes into the video game water. And why not? You could either have a lock on supplying the chips for another company’s machine, or you could build the whole system and put your name on it. Fairchild chose to go the latter route, and the chipmaker had an ace up its corporate sleeve – something they felt would change the video game industry permanently.

It goes without saying that video games were big business in the 1970s, but sometimes getting a look at the players attempting to make their name on that particular field is a good indicator of just how big the business was. Take Fairchild Semiconductor, for example – a well-known player in the integrated circuit business already, Fairchild dipped its toes into the video game water. And why not? You could either have a lock on supplying the chips for another company’s machine, or you could build the whole system and put your name on it. Fairchild chose to go the latter route, and the chipmaker had an ace up its corporate sleeve – something they felt would change the video game industry permanently.

The sad one-two punch to this story is as follows:

- Fairchild’s new system did have something that would permanently change the video game industry, an industry-standard-setting new twist whose influence can still be felt today.

- Fairchild’s new system wouldn’t survive long enough in the market to really reap the benefit of that revolutionary new gimmick.

Fairchild’s Video Entertainment System came, as did most dedicated consoles of the day, with games built into the machine’s hardware: a simple game of hockey and a Pong-like tennis game. The VES’ two hard-wired controllers were an interesting new twist unto themselves, literally: players would hold the bulk of the controller in one hand and manipulate the control – a combination of multi-directional joystick, twisting paddle and “plunger” – with the other. And when hockey and tennis got old, you could buy extra cartridges and slide them into the slot provided on the front of the system’s main panel.

Fairchild’s system was the first home video game that could be programmed with additional games sold in cartridge form. These optional extra games were housed in their own ROM chips in the cartridges, and Fairchild promised that many future titles would be available. And in 1976, in a consumer world where the console wars, thus far, had been waged by systems that couldn’t be expanded or added onto, at least not since the Magnavox Odyssey with its add-on Shooting Gallery light gun, this was big news. So long as new cartridges were made available, and the games were fresh enough to keep the game-buying public entertained, Fairchild didn’t have to worry about churning out another machine in the next year. The VES simply wouldn’t get old. (At least that was the theory.)

Fairchild’s “Videocarts,” as they were called, were big, bright yellow, and covered with bold, day-glo label artwork that was certainly fancier than anything the machine could actually put on a TV screen. But when the first of these multi-game cartridges added not just one but several new games to the existing system, consumers saw the appeal immediately. Fairchild actually wound up backlogged, with more demand for the VES than they initially had a supply.

One year into the VES’s lifetime, however, another player emerged on the field, and its product had a similar name and operated on the same basic idea. And while Atari’s Video Computer System didn’t even have a built-in game going for it, it did have the marketing might of the makers of Pong behind it, and an established distribution network through Sears. Fairchild’s reaction would almost seem, in hindsight, to indicate that they knew they were up against a formidable foe: the VES was rechristened Channel F, to avoid confusion with Atari’s new cartridge-based system, and the games on Fairchild’s “Videocarts” grew a little more elaborate, now frequently taking up an entire cartridge’s memory with a single game.

Fairchild stayed behind the Channel F through 1978, but Atari’s gains in the home video game market by that time made Channel F look like an also-ran. Other systems – Magnavox’s Odyssey2 and Mattel Electronics’ Intellivision among them – were also preparing to go on the market, trying to be the next Atari-sized success story. Fairchild didn’t feel it could compete, and found an unlikely buyer for the Channel F inventory and intellectual properties. Tool and instrument maker Zircon International took on the challenge, even going so far as to retool the console’s look (though not its internal hardware) and re-releasing it as the Zircon Channel F System II in 1982, at the height of video game mania – and on the eve of the crash. A few extra games were released through Zircon, and then they gave up the ghost as well. The first programmable cartridge-based system finally dead-ended.

Here, then, is a brief guide to the oft-overlooked Channel F and its games. And before you write off the influence of Fairchild’s wonder machine of the 1970s, ask yourself this: does your Game Boy Advance still run its games from pre-programmed cartridges? Players may have tuned out on Channel F over 25 years ago, but the system’s legacy still remains.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=448]

Odyssey 3000

It adds nothing to the Odyssey 2000’s “four action-packed video games,” but the Odyssey 3000 is a quantum leap in the design aesthetic of the console itself. Finally breaking away from the basic casing design that had been in place since the Odyssey 100, Odyssey 3000 packs four games (well, really just three plus a Tennis “practice mode”) into a sleek, futuristic-looking black wedge with highlights that almost anticipate – believe it or not – the look of the computer screens in Star Trek: The Next Generation (though to be more realistic, it may have been influenced by the design line of Atari’s Fuji logo). The controllers are detachable but hardwired, and nestle snugly into the console itself.

It adds nothing to the Odyssey 2000’s “four action-packed video games,” but the Odyssey 3000 is a quantum leap in the design aesthetic of the console itself. Finally breaking away from the basic casing design that had been in place since the Odyssey 100, Odyssey 3000 packs four games (well, really just three plus a Tennis “practice mode”) into a sleek, futuristic-looking black wedge with highlights that almost anticipate – believe it or not – the look of the computer screens in Star Trek: The Next Generation (though to be more realistic, it may have been influenced by the design line of Atari’s Fuji logo). The controllers are detachable but hardwired, and nestle snugly into the console itself.

Odyssey 2000

After the baffling backward step of the Odyssey 400, Magnavox’s Odyssey 2000 saw a return to the Pong-inspired, single-paddle control scheme, with digital scoring restored as well – Magnavox had decided to rest the Brown Box design (and the subsequent variations on it) permanently in favor of, once again, the General Instruments AY-3-8500 “Pong on a chip” processor. Packaged in a red casing, this would be the last anyone would see of the smoothly rounded-off, integrated Odyssey console. The next system to bear the name would return to its roots – with wired controllers that weren’t necessarily stuck to the main console – and look forward, with a futuristic new design that stands up even today.

After the baffling backward step of the Odyssey 400, Magnavox’s Odyssey 2000 saw a return to the Pong-inspired, single-paddle control scheme, with digital scoring restored as well – Magnavox had decided to rest the Brown Box design (and the subsequent variations on it) permanently in favor of, once again, the General Instruments AY-3-8500 “Pong on a chip” processor. Packaged in a red casing, this would be the last anyone would see of the smoothly rounded-off, integrated Odyssey console. The next system to bear the name would return to its roots – with wired controllers that weren’t necessarily stuck to the main console – and look forward, with a futuristic new design that stands up even today.

Night Driver

The Game: You’re racing the Formula One circuit by the glow of your headlights alone – avoid the markers along the side of the road and other passing obstacles…if you can see them in time. (Atari, 1976)

The Game: You’re racing the Formula One circuit by the glow of your headlights alone – avoid the markers along the side of the road and other passing obstacles…if you can see them in time. (Atari, 1976)

Memories: Aside from the very cool cockpit cabinet of the sit-down version of Night Driver, there’s a reason why it earns a spot in video game history. Go ahead and see if you can guess what it is. Give up? It’s the first time that a representation of depth appeared in the graphics of a video game. Until this point, home and arcade video games had presented their playing fields as strictly two-dimensional spaces: they were seen from straight overhead, or from a side-on view.

Death Race

The Game: Two players control one car each, careening freely around an arena filled with zombies. Faced with zombie-fication at the pedestrian crossing of the undead, the drivers have only one option: run over their opponents! Each zombie that’s squashed leaves a grave marker behind that becomes an unmovable obstacle to zombies and cars alike. Whoever has run over the most zombies by the end of the timed game wins. (Exidy, 1976)

The Game: Two players control one car each, careening freely around an arena filled with zombies. Faced with zombie-fication at the pedestrian crossing of the undead, the drivers have only one option: run over their opponents! Each zombie that’s squashed leaves a grave marker behind that becomes an unmovable obstacle to zombies and cars alike. Whoever has run over the most zombies by the end of the timed game wins. (Exidy, 1976)

Memories: Death Race, which didn’t even come within shouting distance of having anything to do with the movie of the same name, was the arcade game that sparked the very first protests about violence in video games. Those protests go on to this very day, with games like the latest iteration of Grand Theft Auto and Bully drawing fire for depicting various kinds of real world violence. Compared to those much more recent games, it’s almost laughable to think that the abstraction of Death Race was where some parents first drew the line. Why? Because Death Race was the first person to put stick figures – a representation of a human being – on the screen and let you do something nasty to them.

Datsun 280 ZZZAP!

The Game: Get behind the wheel for a late-night drive – at high speeds! The only visual clues about the road ahead are the reflectors zooming past. Avoid going off the road and go the distance. (Midway, 1976)

Memories: In the wake of Nolan Bushnell’s gambit to topple the exclusive arcade distribution system (see the Phosphor Dot Fossils entry for Tank!), a clever move that would turn modern antitrust lawyers into a pack of baying wolves, direct copying of other companies’ arcade code and circuitry was off the table. Now the competition merely duplicated Atari‘s game concepts rather than every line of code.

Barricade

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Ramtek, 1976)

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Ramtek, 1976)

Memories: If you’re a fan of the “Light Cycle” concept made popular by Tron (both the movie and the game), this is where it all started, with an obscure game from a relatively obscure manufacturer. But that obscurity isn’t earned by a game that essentially launched and entire genre.

The Amazing Maze Game

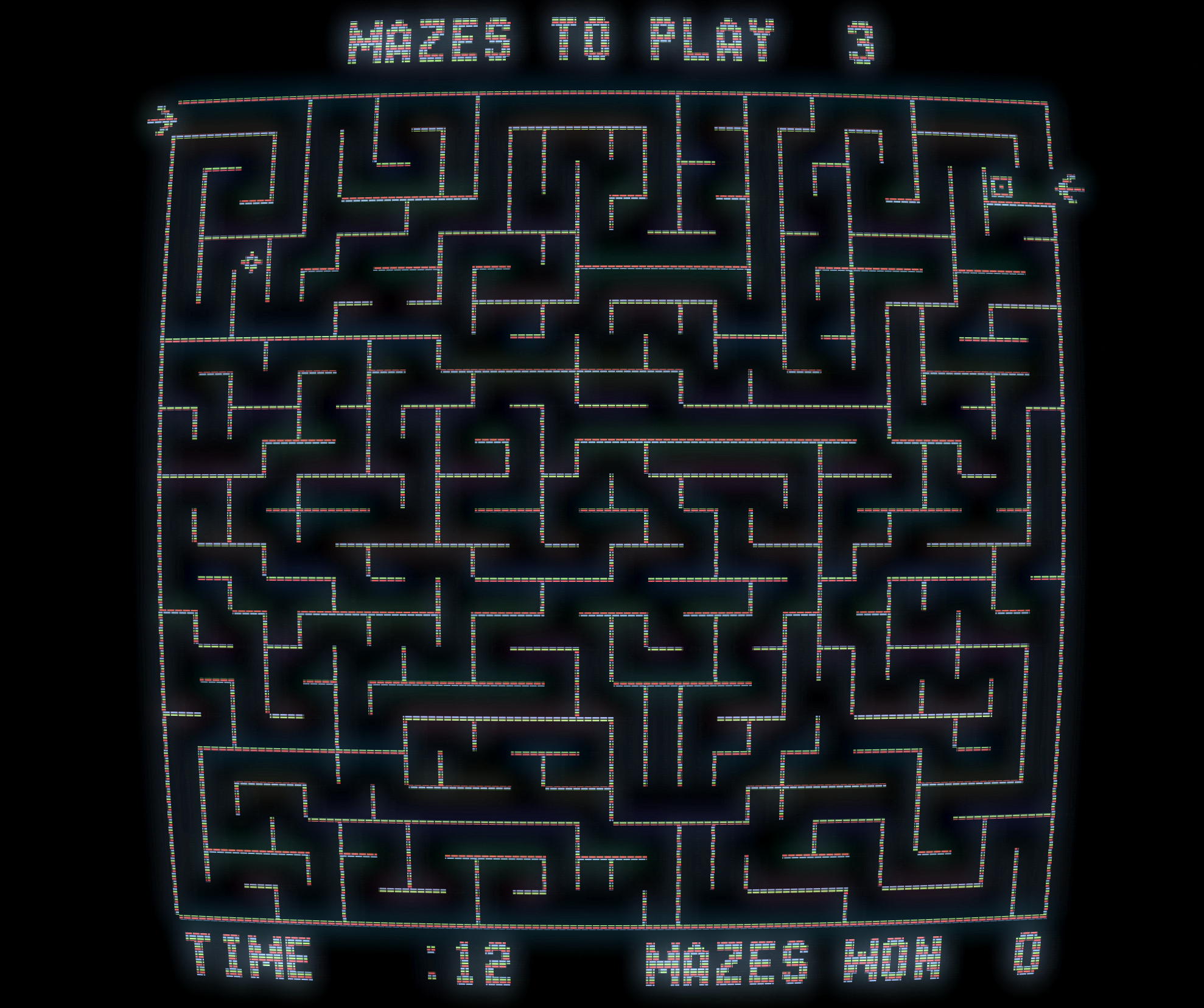

The Game: You control a dot making its way through a twisty maze with two exits – one right behind you and one across the screen from you. The computer also controls a dot which immediately begins working its way toward the exit behind you. The game is simple: you have to guide your dot through the maze to the opposite exit before the computer does the same. If the computer wins twice, the game is over. (Midway, 1976)

The Game: You control a dot making its way through a twisty maze with two exits – one right behind you and one across the screen from you. The computer also controls a dot which immediately begins working its way toward the exit behind you. The game is simple: you have to guide your dot through the maze to the opposite exit before the computer does the same. If the computer wins twice, the game is over. (Midway, 1976)

Memories: Not, strictly speaking, the first maze game, Midway’s early B&W arcade entry The Amazing Maze Game bears a strong resemblence to that first game, which was Atari’s Gotcha. Gotcha was almost identical, except that its joystick controllers were topped by pink rubber domes, leading to Gotcha being nicknamed “the boob game.” Amazing Maze was just a little bit more austere by comparison.

Odyssey 300

Taking Atari’s lead for the first time, the Odyssey 300 – in its bright yellow shell – saw the console abandoning the trio of horizontal/vertical/English controls that had been in place since the original Odyssey. In addition to mimicking the all-in-one controls of Atari’s Pong, Odyssey 300 – still boasting the standard Tennis, Hockey and Smash variations of its predecessors – introduced digital on-screen scoring. The Odyssey games were no longer reliant on the honor system: at 15 points, one player won the game.

Taking Atari’s lead for the first time, the Odyssey 300 – in its bright yellow shell – saw the console abandoning the trio of horizontal/vertical/English controls that had been in place since the original Odyssey. In addition to mimicking the all-in-one controls of Atari’s Pong, Odyssey 300 – still boasting the standard Tennis, Hockey and Smash variations of its predecessors – introduced digital on-screen scoring. The Odyssey games were no longer reliant on the honor system: at 15 points, one player won the game.

The Game: Long before Frogger and Frog Bog, there were simply Frogs, the original arcade amphibians. One or two frogs hop along a lily pad at the bottom of the screen, scoping out tasty flies to eat. When you’ve got a morsel in your frog’s reach, jump and try to activate your frog’s tongue at just the right time. (You’ll know if you’ve snared a meal because your frog will seem to ascend the screen in heavenly bliss.) Whoever has the most points at the end of the timed game is the supreme frog. (Gremlin, 1978)

The Game: Long before Frogger and Frog Bog, there were simply Frogs, the original arcade amphibians. One or two frogs hop along a lily pad at the bottom of the screen, scoping out tasty flies to eat. When you’ve got a morsel in your frog’s reach, jump and try to activate your frog’s tongue at just the right time. (You’ll know if you’ve snared a meal because your frog will seem to ascend the screen in heavenly bliss.) Whoever has the most points at the end of the timed game is the supreme frog. (Gremlin, 1978)

The Game: Trade those pads in for pixels and get ready to hit the gridiron. Each player controls a football team represented by Xs or Os, and uses a keypad to select offensive and defensive maneuvers – and the trakball to tear across the turf as fast as the player can move it. Additional quarters buy additional playing time (each quarter gets two minutes of play). Whoever has the highest score at the end of the game is the winner; later four-player variations sported additional trakballs so the offensive player could control his team’s quarterback and another could control the receiver for passing plays, while there were now two independent players on the defensive team. (Atari, 1978)

The Game: Trade those pads in for pixels and get ready to hit the gridiron. Each player controls a football team represented by Xs or Os, and uses a keypad to select offensive and defensive maneuvers – and the trakball to tear across the turf as fast as the player can move it. Additional quarters buy additional playing time (each quarter gets two minutes of play). Whoever has the highest score at the end of the game is the winner; later four-player variations sported additional trakballs so the offensive player could control his team’s quarterback and another could control the receiver for passing plays, while there were now two independent players on the defensive team. (Atari, 1978)

The Game: Piloting a mobile cannon around a cluttered playfield, you have but one task: clear the screen of mines, without blowing yourself up, in the time allotted. If you don’t clear the screen, or you manage to detonate a mine so close to yourself that it takes you out, the game is over. If you do clear all the mines, you get a free chance to try it again. Two players can also try to clear the minefield simultaneously. (Gremlin, 1978)

The Game: Piloting a mobile cannon around a cluttered playfield, you have but one task: clear the screen of mines, without blowing yourself up, in the time allotted. If you don’t clear the screen, or you manage to detonate a mine so close to yourself that it takes you out, the game is over. If you do clear all the mines, you get a free chance to try it again. Two players can also try to clear the minefield simultaneously. (Gremlin, 1978) The Game: Watch for falling rocks – because it’s your job to catch them. You control a series of containers arranged in a vertical row, and your task is to catch all of the rocks, without fail, not letting a single one of them hit the ground. The more rocks you catch, the more containers you’ll fill, and you’ll be left with fewer, and smaller, containers. If you let a rock through your defenses too many times, the game’s over. And you’ll probably be hit in the head with a lot of rocks. Neither outcome is really a good thing. (Atari, 1978)

The Game: Watch for falling rocks – because it’s your job to catch them. You control a series of containers arranged in a vertical row, and your task is to catch all of the rocks, without fail, not letting a single one of them hit the ground. The more rocks you catch, the more containers you’ll fill, and you’ll be left with fewer, and smaller, containers. If you let a rock through your defenses too many times, the game’s over. And you’ll probably be hit in the head with a lot of rocks. Neither outcome is really a good thing. (Atari, 1978)

The Game: Two players each control a fearsome armored fighting vehicle on a field of battle littered with obstacles (or not, depending upon the agreed-upon game variation). The two tanks pursue each other around the screen, trying to

The Game: Two players each control a fearsome armored fighting vehicle on a field of battle littered with obstacles (or not, depending upon the agreed-upon game variation). The two tanks pursue each other around the screen, trying to  The final member of the Odyssey stand-alone console family tree, the Odyssey 4000 boasts more games than any of its predecessors since Ralph Baer’s original Odyssey, and was only the second of the dedicated Odyssey consoles to feature color (after the experimental Odyssey 500). And for those who have ever held the joystick of a Magnavox Odyssey2 in their hands, the Odyssey 4000 offers another familiar element – its joysticks are exactly the same mold as those of the Odyssey2, only rotated 90 degrees, and sporting some major differences in internal mechanisms. Though multidirectional, the joysticks are designed to favor vertical movement and offer some resistance to horizontal movement.

The final member of the Odyssey stand-alone console family tree, the Odyssey 4000 boasts more games than any of its predecessors since Ralph Baer’s original Odyssey, and was only the second of the dedicated Odyssey consoles to feature color (after the experimental Odyssey 500). And for those who have ever held the joystick of a Magnavox Odyssey2 in their hands, the Odyssey 4000 offers another familiar element – its joysticks are exactly the same mold as those of the Odyssey2, only rotated 90 degrees, and sporting some major differences in internal mechanisms. Though multidirectional, the joysticks are designed to favor vertical movement and offer some resistance to horizontal movement.  The Game: Up to two players control markers that leave a trail of dominos in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by laying a wall of dominos around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to run into their own walls. Coming into contact with a line of dominos, either you own or someone else’s, collapses your own trail and ends your turn. The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Atari, 1977)

The Game: Up to two players control markers that leave a trail of dominos in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by laying a wall of dominos around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to run into their own walls. Coming into contact with a line of dominos, either you own or someone else’s, collapses your own trail and ends your turn. The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Atari, 1977) Back in the heady days of Nolan Bushnell-managed Atari, when the home versions of games like Pong and Stunt Cycle were making decent money, and the sky seemed to be the limit, and the 2600 was nothing more than a promising idea on the horizon, anything could’ve been the next big thing. And not even necessarily anything that was a video game. Despite all of the legendary stories of executive meetings in hot tubs, on-the-job marijuana use, and blue-jeans-as-businesswear, it may just be that nothing provides as much concrete evidence of the heady, psychedelic early days of Atari as one of their most obscure products: Atari Video Music.

Back in the heady days of Nolan Bushnell-managed Atari, when the home versions of games like Pong and Stunt Cycle were making decent money, and the sky seemed to be the limit, and the 2600 was nothing more than a promising idea on the horizon, anything could’ve been the next big thing. And not even necessarily anything that was a video game. Despite all of the legendary stories of executive meetings in hot tubs, on-the-job marijuana use, and blue-jeans-as-businesswear, it may just be that nothing provides as much concrete evidence of the heady, psychedelic early days of Atari as one of their most obscure products: Atari Video Music.  The Game: The first Channel F “Videocart” packs three games into one bright yellow package. Shooting Gallery is a straightforward target practice game in which players try to draw a bead on a moving target. Tic-Tac-Toe is the timeless game of strategy in small, enclosed spaces, and Quadradoodle is a simple paint program, long, long before its time. (Fairchild, 1976)

The Game: The first Channel F “Videocart” packs three games into one bright yellow package. Shooting Gallery is a straightforward target practice game in which players try to draw a bead on a moving target. Tic-Tac-Toe is the timeless game of strategy in small, enclosed spaces, and Quadradoodle is a simple paint program, long, long before its time. (Fairchild, 1976) The Game: Activated by leaving a cartridge out of the slot, powering the system up and pressing one of the selector keys, Tennis and Hockey are built into the system. Timed games can be selected, and the traditional rules of each sport apply. (Fairchild, 1976)

The Game: Activated by leaving a cartridge out of the slot, powering the system up and pressing one of the selector keys, Tennis and Hockey are built into the system. Timed games can be selected, and the traditional rules of each sport apply. (Fairchild, 1976) With the same trio of games as the Odyssey 400 – Tennis, Hockey/Soccer and Smash – the Odyssey 500, released in 1976 by Magnavox, would appear to not be much of an upgrade, but in fact, it’s an absolutely critical turning point for home video games: the Odyssey 500 did away with squares and rectangles to represent the player, and introduced character sprites – hardware-generated characters that roughly mimicked the shape of a human being.

With the same trio of games as the Odyssey 400 – Tennis, Hockey/Soccer and Smash – the Odyssey 500, released in 1976 by Magnavox, would appear to not be much of an upgrade, but in fact, it’s an absolutely critical turning point for home video games: the Odyssey 500 did away with squares and rectangles to represent the player, and introduced character sprites – hardware-generated characters that roughly mimicked the shape of a human being.

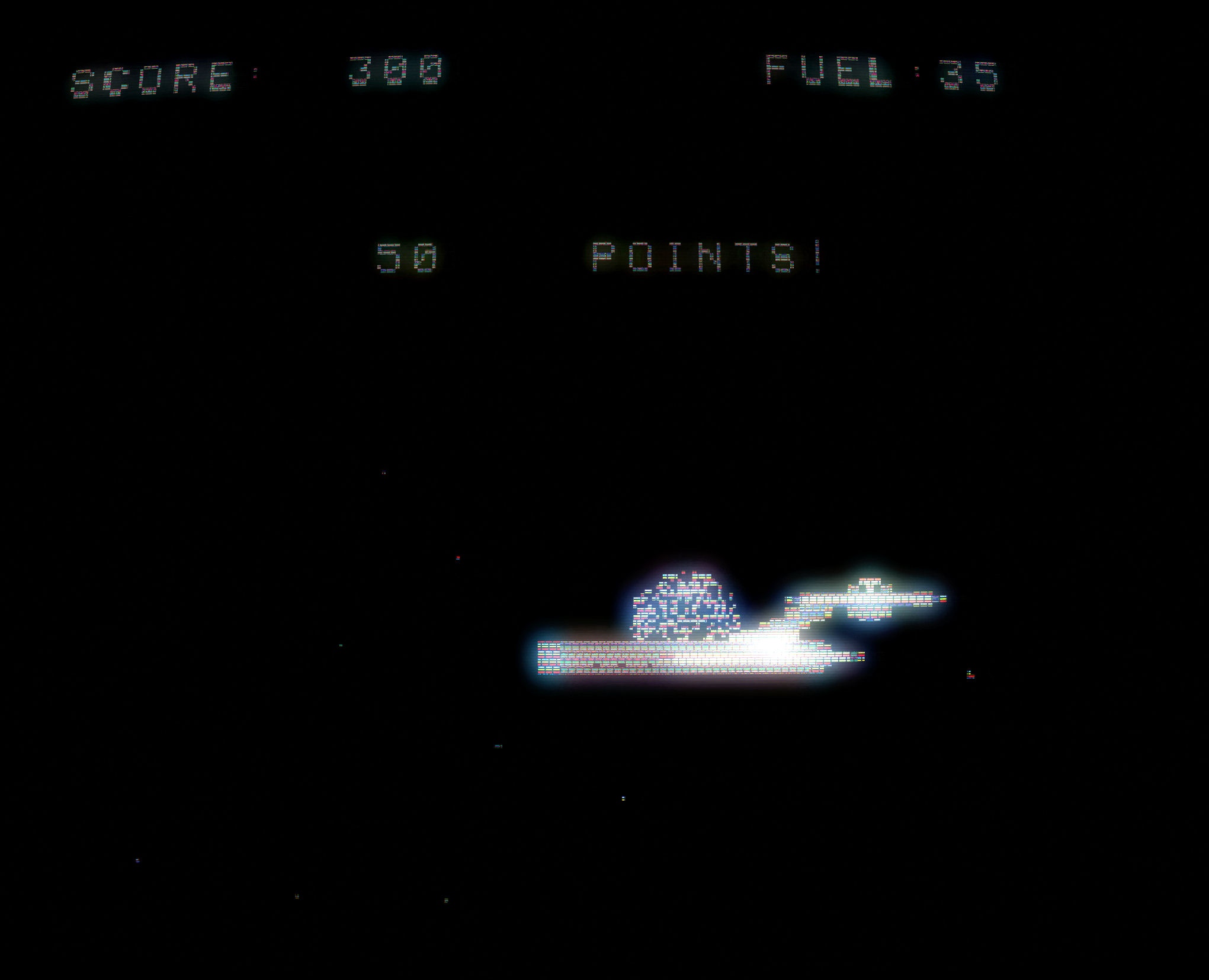

The Game: Climb into the cockpit of Starship Atari for deep space combat duty. Your mission is simple: wipe out every alien ship you see, as quick as possible, while taking as little incoming fire as possible. Take too much damage, and your fighting days are over. (Atari, 1976)

The Game: Climb into the cockpit of Starship Atari for deep space combat duty. Your mission is simple: wipe out every alien ship you see, as quick as possible, while taking as little incoming fire as possible. Take too much damage, and your fighting days are over. (Atari, 1976)