Battlezone

The Game: As the pilot of a heavy tank, you wander the desolate battlefield, trying to wipe out enemy tanks and landing vehicles. (Atari, 1980)

The Game: As the pilot of a heavy tank, you wander the desolate battlefield, trying to wipe out enemy tanks and landing vehicles. (Atari, 1980)

Memories: Though the above description is exceedingly simple, Battlezone was another pillar of Atari’s stable of outstanding vector graphics games (which also included Tempest and Asteroids). With its two-stick control system, mimicking a real tank’s controls, its slowly lumbering game play, and its periscope-like screen, Battlezone was, for its day, an incredibly cool and realistic game (with a huge cabinet too).

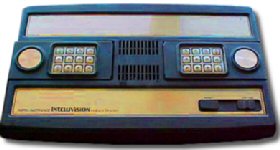

Intellivision

It was touted as “Intelligent Television,” a new peak in video game interaction, and hey, with those numeric keypads on the controllers, there was even a slight hint that there would be wholesome educational games on the way. Mattel’s Intellivision – released in 1980 to compete with the Atari 2600 and the Odyssey 2 – was supposed to be the next big thing.

It was touted as “Intelligent Television,” a new peak in video game interaction, and hey, with those numeric keypads on the controllers, there was even a slight hint that there would be wholesome educational games on the way. Mattel’s Intellivision – released in 1980 to compete with the Atari 2600 and the Odyssey 2 – was supposed to be the next big thing.

But Intellivision had numerous things working against it. By the time Mattel introduced its own game console, the Atari 2600 had established a foothold – and the ColecoVision and Atari 5200  were only a year or two away from being on the market. From whatever direction one looked, the Intellivision was in the wrong place at the wrong time. One of the system’s big attractions – Mattel’s promise to release a computer peripheral – was beset by numerous delays, and only after the company was subjected to Federal Trade Commission inquries did Mattel put the peripheral on the market. The eventual release of the computer peripheral only happened to prevent legal disaster: it fell far short of expectations and certainly didn’t transform the Intellivision into the promised home computer – but despite that, nearly every game

were only a year or two away from being on the market. From whatever direction one looked, the Intellivision was in the wrong place at the wrong time. One of the system’s big attractions – Mattel’s promise to release a computer peripheral – was beset by numerous delays, and only after the company was subjected to Federal Trade Commission inquries did Mattel put the peripheral on the market. The eventual release of the computer peripheral only happened to prevent legal disaster: it fell far short of expectations and certainly didn’t transform the Intellivision into the promised home computer – but despite that, nearly every game  manufacturer since the Intellivision’s time has announced a computer add-on, and like Mattel, few of them have delivered on the promise.

manufacturer since the Intellivision’s time has announced a computer add-on, and like Mattel, few of them have delivered on the promise.

Though they were seen as a nuisance at the time, Intellivision’s “disc pad” controllers were very early progenitors of the same style of controller that Nintendo made commonplace with its NES joypads almost a decade later. And even though Mattel and numerous third-party manufacturers made sure that the Intellivision library was well-stocked with popular arcade titles, the Intellivision’s fortè was over-complicated games like Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Utopia, and Tron Maze-a-Tron. They went over great with enthusiasts of complicated board and role-playing games, but alienated players who had bought the Intellivision in the simple hope of finding more faithful renditions of arcade classics than could be found on the Atari 2600.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=42,127]

Intellivision extras: from left to right, an optional clamp-on joystick to make the clumsy joy-disc controllers more manageable, the abandoned General Instrument PlayCable peripheral (essentially an early cable modem that could be used to download games from a special cable channel, tested in only a few markets between 1981 and 1983), and the ill-fated Intellivision computer keyboard add-on.

Intellivision extras: from left to right, an optional clamp-on joystick to make the clumsy joy-disc controllers more manageable, the abandoned General Instrument PlayCable peripheral (essentially an early cable modem that could be used to download games from a special cable channel, tested in only a few markets between 1981 and 1983), and the ill-fated Intellivision computer keyboard add-on.

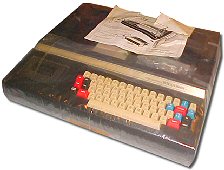

Atari Home Computers

Atari’s popular computer line was never in the game plan of the company’s founding fathers.

Atari’s popular computer line was never in the game plan of the company’s founding fathers.

Neither was making the Atari VCS one of the longest-lived consoles in the history of video gaming. And neither was selling Atari to Warner Communications. But the latter is exactly what Nolan Bushnell was forced to do in 1977. Faced with diminshing cash flow and an uncertain consumer market that had washed its hands of the home video game “fad” once already, Bushnell had to either find a corporate buyer to keep Atari alive, or close the company’s doors forever. Warner swept in and bought the company, and the new Warner-appointed CEO Ray Kassar not only refused to pull the plug on the VCS (Bushnell had already given up hope on the console maintaining its profitability), but opened a new home computer division. The mandate was simple: Atari’s computers should be invaluable for home and business use…and they should play some great games.

The cultural clashes between Bushnell’s old guard and Kassar’s old school business acumen are legendary, and those power struggles eventually got Atari’s founder removed from the company’s board. In the meantime, Atari’s computer line launched successfully in 1979 as one of the very first low-priced competitors to the pricier Apple II home computers, and before Commodore’s series of consumer-priced post-PET computers. The 16K Atari 400, with its membrane keyboard, and the 48K Atari 800 led the pack, complete with cassette and floppy disk drives. As the video game market collapsed and gave way to the home computer market, Atari followed these models up with the Atari 1200, 600XL, 800XL and 1200XL.

That Kassar was gunning for Apple is ironic in hindsight. Prior to the Warner sale, Bushnell had employed a young computer enthusiast named Steve Jobs, and on one occasion, Jobs and his best friend Steve Wozniak had collaborated on the design and programming of an arcade game called Breakout. When Wozniak and Jobs created the Apple I as a hobby project in their spare time, they showed it first to Atari; Bushnell wasn’t interested in venturing into home computers at the time, but pointed them in the direction of venture capitalist Don Valentine (who later funded a game-making startup called Electronic Arts), who in turn introduced Jobs and Wozniak to Mike Markkula, who provided Apple’s startup capital. Due to Bushnell’s fixation on creating game consoles and not computers, Atari missed out on having its name on the top-selling personal computer of the early 80s.

It was during the mid-80s crash of the video game industry that Atari was once again sold, this time to former Commodore Computer CEO Jack Tramiel. Wanting to re-launch Atari as a home computer maker and use it to get revenge on Commodore (from which he had been forcibly ousted), Tramiel all but eliminated the home video game division, and Warner held on to the arcade division, later selling it to Midway. Amid sweeping personnel changes, Tramiel installed his sons in key positions in the company and chased off many of the remaining game designers who had helped Atari ascend to its pre-crash heyday. A new console, the Atari 7800, was shelved indefinitely despite being a major technological advance among game consoles. Tramiel’s reign saw the introduction of the popular ST series of computers, as well as a lame duck attempt to launch a hybrid game console/low-end personal computer, the Atari XE.

Though many unique plans were on the drawing board, including portable computers that predated Compaq’s first laptop, the Atari ST line couldn’t compete with the PC-compatible juggernaut which also eventually eliminated such competition as the Apple IIGS and Commodore’s Amiga. Atari gave up the ghost on the ST in the early 90s and instead tried to launch a series of PC-compatible desktop machines, but businesses just weren’t ready to do their accounting, inventory and bookkeeping on a machine bearing the same logo as countless video game machines, and it is there that Atari’s computer legacy comes to a quiet, unremarkable end.

In 1996, Tramiel quietly merged Atari with a hard drive manufacturer, JTS, primarily to gain a seat on the latter company’s board. JTS later sold the Atari name and intellectual properties to Hasbro Interactive for a paltry $5 million, and Hasbro returned Atari to some semblance of its former glory by releasing retro-oriented titles like Missile Command and Pong for modern PCs and game systems. Hasbro Interactive eventually ran aground, and the Atari name and properties once again changed hands, this time being bought by French game publisher Infogrames.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=36]

Math-A-Magic! / Echo!

The Game: Wow! We must be in the future, for we now have electronic flash cards! This is more or less the function fulfilled by Math-A-Magic, while Echo is a slightly watered down version of the classic electronic game Simon. (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: Wow! We must be in the future, for we now have electronic flash cards! This is more or less the function fulfilled by Math-A-Magic, while Echo is a slightly watered down version of the classic electronic game Simon. (Magnavox, 1979)

Memories: This may sound a wee bit pretentious, but this “game” – at least the Math-A-Magic! side of things – was instrumental in me getting through some problems comprehending basic math many years ago in grade school. I’m still not a math wizard – I barely passed any applied or theoretical math classes beyond Algebra I in high school and college – but way back when, this actually helped. Who said that video games can’t change anyone’s life for the better?

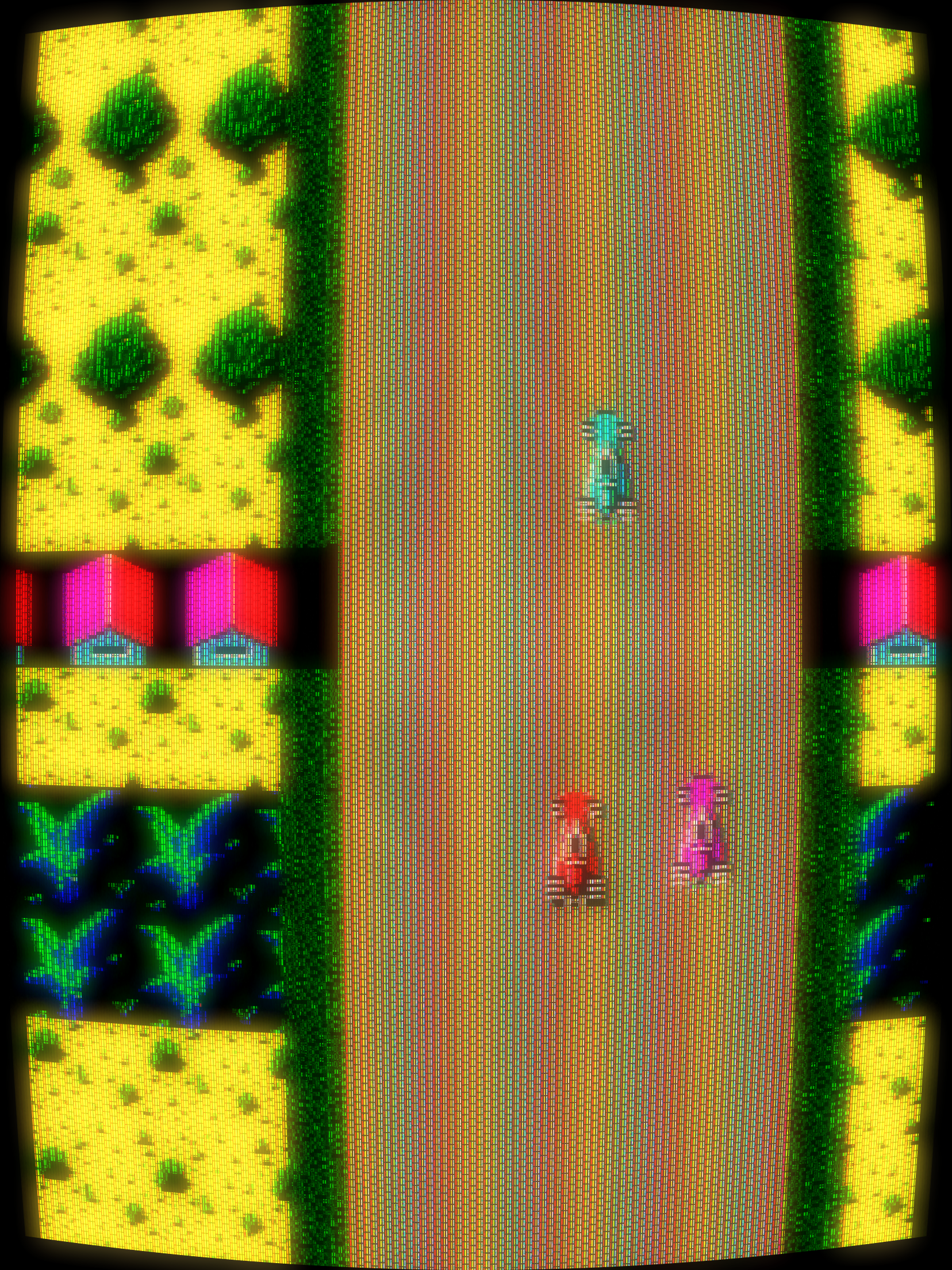

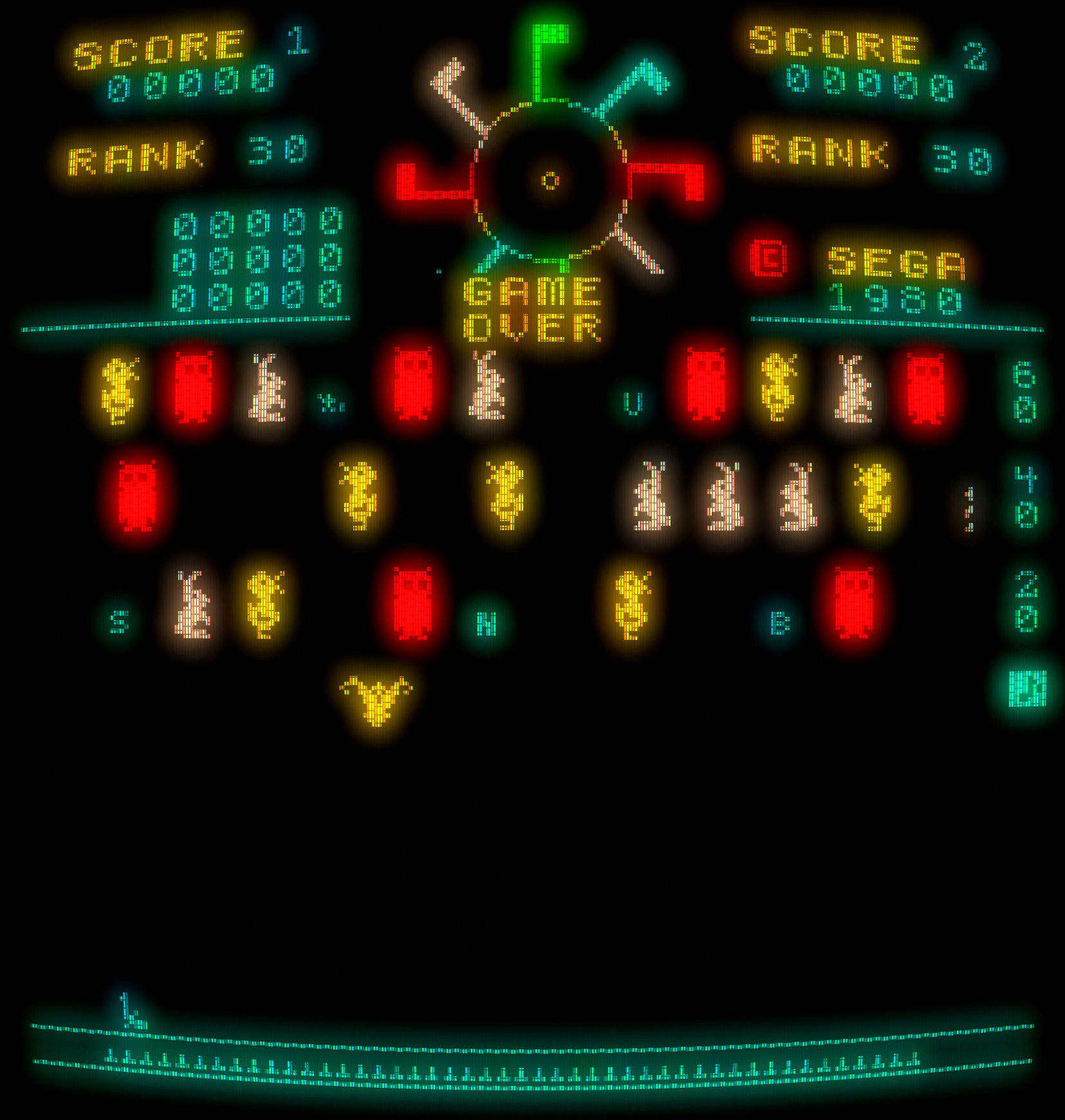

Monaco GP

The Game: Players get behind the wheel of a roaring race car, viewed from overhead, as it navigates a series of roads and occasional tunnels whose width varies dramatically. Tunnels are illuminated only by headlights, which means that collisions with other cars are, if not certain, then at least much more likely. Any collision results in the player’s car having to get into traffic again from a dead standstill at the side of the road. (Sega, 1979)

The Game: Players get behind the wheel of a roaring race car, viewed from overhead, as it navigates a series of roads and occasional tunnels whose width varies dramatically. Tunnels are illuminated only by headlights, which means that collisions with other cars are, if not certain, then at least much more likely. Any collision results in the player’s car having to get into traffic again from a dead standstill at the side of the road. (Sega, 1979)

Memories: Monaco GP looks like just about any other overhead racing game, though it certainly upped the ante in terms of color. Its interesting take on the concept of “road widening” also made it uniquely frustrating and amusing at the same time. But as similar as it may seem to rest of the overhead-view racing games of its day, Monaco GP does hold one distinction in video game history.

The Game: The invaders are back, and this time they plan on making quick work of Earth’s defenses. Columns of alien invaders descend from space, staying safely outside of the range of the player’s cannon. A few aliens at a time break formation and attempt to reach the player’s floating stockpiles of ordnance and extra ships floating in the center of the screen; if the aliens are able to reach these items, the player will lose a life. The only option is to take out the invaders before they succeed. (Universal, 1980)

The Game: The invaders are back, and this time they plan on making quick work of Earth’s defenses. Columns of alien invaders descend from space, staying safely outside of the range of the player’s cannon. A few aliens at a time break formation and attempt to reach the player’s floating stockpiles of ordnance and extra ships floating in the center of the screen; if the aliens are able to reach these items, the player will lose a life. The only option is to take out the invaders before they succeed. (Universal, 1980)

The Game: Step right up, put your quarter on the table (well, okay, technically in the slot), and take your best shot. There are plenty of targets to hit, but no big plush bears to win. If you don’t take out the ducks before they reach the bottom row, they don’t cycle back to the top like the other targets – they start flying and can take serious amounts of ammo off your hands and end the game early! (1980, Sega)

The Game: Step right up, put your quarter on the table (well, okay, technically in the slot), and take your best shot. There are plenty of targets to hit, but no big plush bears to win. If you don’t take out the ducks before they reach the bottom row, they don’t cycle back to the top like the other targets – they start flying and can take serious amounts of ammo off your hands and end the game early! (1980, Sega) The Game: You’re alone in a maze filled with armed, hostile robots who only have one mission – to kill you. If you even so much as touch the walls, you’ll wind up dead. You’re a little bit faster than the robots, and you have human instinct on your side…but even that won’t help you when Evil Otto, a deceptively friendly and completely indestructible smiley face, appears to destroy you if you linger too long in any one part of the maze. The object of the game? Try to stay alive however long you can. (Stern, 1980)

The Game: You’re alone in a maze filled with armed, hostile robots who only have one mission – to kill you. If you even so much as touch the walls, you’ll wind up dead. You’re a little bit faster than the robots, and you have human instinct on your side…but even that won’t help you when Evil Otto, a deceptively friendly and completely indestructible smiley face, appears to destroy you if you linger too long in any one part of the maze. The object of the game? Try to stay alive however long you can. (Stern, 1980) The Game: Why worry about space invaders when there are more pressing earthly threats? Players guide a mobile cannon at the bottom of the screen, trying to take out a constant barrage of balloon bombers dropping live bombs. A direct hit to the cannon costs the player a “life,” but if the player allows a bomb to hit bottom, the results can be almost as dangerous: bombs crater the surface that the player’s cannon moves across, and allowing those pits to collect on the surface can severely limit the player’s movements, to the point of leaving the cannon a motionless sitting duck for the next round of balloon bombs, or a plane that periodically drops cluster bombs from overhead. (Taito, 1980)

The Game: Why worry about space invaders when there are more pressing earthly threats? Players guide a mobile cannon at the bottom of the screen, trying to take out a constant barrage of balloon bombers dropping live bombs. A direct hit to the cannon costs the player a “life,” but if the player allows a bomb to hit bottom, the results can be almost as dangerous: bombs crater the surface that the player’s cannon moves across, and allowing those pits to collect on the surface can severely limit the player’s movements, to the point of leaving the cannon a motionless sitting duck for the next round of balloon bombs, or a plane that periodically drops cluster bombs from overhead. (Taito, 1980) The Game: As the pilot of a lone space cruiser, you must try to clear the spaceways of a swarm of free-floating (and yet somehow deluxe) asteroids, but the job isn’t easy – Newton’s laws of motion must be obeyed, even by asteroids. When you blow a big rock into little chunks, those chunks go

The Game: As the pilot of a lone space cruiser, you must try to clear the spaceways of a swarm of free-floating (and yet somehow deluxe) asteroids, but the job isn’t easy – Newton’s laws of motion must be obeyed, even by asteroids. When you blow a big rock into little chunks, those chunks go  The Game: Those pesky invaders from space are back, and this time they’ve devised a handy delivery system that drops entire columns of kamikaze invaders and motherships through a series of airborne chutes from an orbiting Stern command ship. Players can try to intercept invaders as they plummet toward Earth, but as their impact sends a cloud of debris spreading outward which can also destroy the player’s cannon, avoidance is a perfectly acceptable (if not exactly high-scoring) survival strategy. (Stern [under license from Union Denshi Kogyo Company], 1980)

The Game: Those pesky invaders from space are back, and this time they’ve devised a handy delivery system that drops entire columns of kamikaze invaders and motherships through a series of airborne chutes from an orbiting Stern command ship. Players can try to intercept invaders as they plummet toward Earth, but as their impact sends a cloud of debris spreading outward which can also destroy the player’s cannon, avoidance is a perfectly acceptable (if not exactly high-scoring) survival strategy. (Stern [under license from Union Denshi Kogyo Company], 1980) The Game: One or two players are at the controls of speedy ground assault vehicles which can zip around an enclosed maze of open areas and buildings with almost mouse-like speed. Heavy tanks and armed helicopters routinely appear in this maze, attempting to shoot any player vehicles they spot; the player(s) can, in turn, fire back at both of these vehicles. Caution: a damaged tank may still be able to draw a bead, so it’s best to keep firing until the tanks are completely destroyed. (Cinematronics, 1980)

The Game: One or two players are at the controls of speedy ground assault vehicles which can zip around an enclosed maze of open areas and buildings with almost mouse-like speed. Heavy tanks and armed helicopters routinely appear in this maze, attempting to shoot any player vehicles they spot; the player(s) can, in turn, fire back at both of these vehicles. Caution: a damaged tank may still be able to draw a bead, so it’s best to keep firing until the tanks are completely destroyed. (Cinematronics, 1980) The Game: Zylon warships are on the rampage, blasting allied basestars out of the sky and wreaking havoc throughout the galaxy. Your orders are to track down the fast-moving raiders and destroy them before they can do any more damage. You have limited shields and weapons at your disposal, and a battle computer which is vital to your mission (though critical damage to your space fighter can leave you without that rather important piece of equipment). The game is simple: destroy until you are destroyed, and defend friendly installations as long as you can. (Atari, 1979)

The Game: Zylon warships are on the rampage, blasting allied basestars out of the sky and wreaking havoc throughout the galaxy. Your orders are to track down the fast-moving raiders and destroy them before they can do any more damage. You have limited shields and weapons at your disposal, and a battle computer which is vital to your mission (though critical damage to your space fighter can leave you without that rather important piece of equipment). The game is simple: destroy until you are destroyed, and defend friendly installations as long as you can. (Atari, 1979) The Game: You’re the commander of a small squad of robots, and your opponent – be it a second player or the computer – is commanding a similar platoon o’ droids. Your job is to avoid the enemy’s robots while you wait for your robots to reach the enemy commander. Of course, the enemy’s robots could reach you first, but that’s another story. The only control you have over your robots is to press the action button and call them toward you. The robots fight hand-to-hand, rather than shooting, and your robots may become incapacitated. You can leap into the fray and touch one of your malfunctioning robots to repair it and return it to the fight, but in so doing, you run a risk of being captured by enemy robots. (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: You’re the commander of a small squad of robots, and your opponent – be it a second player or the computer – is commanding a similar platoon o’ droids. Your job is to avoid the enemy’s robots while you wait for your robots to reach the enemy commander. Of course, the enemy’s robots could reach you first, but that’s another story. The only control you have over your robots is to press the action button and call them toward you. The robots fight hand-to-hand, rather than shooting, and your robots may become incapacitated. You can leap into the fray and touch one of your malfunctioning robots to repair it and return it to the fight, but in so doing, you run a risk of being captured by enemy robots. (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: It’s all the thrills of pinball, minus approximately 75% of the excitement! Use your joystick to control the plunger tension and launch your ball into play. Use the action button to pop the flippers, keeping your ball on the field and out of trouble. The bumpers and spinner score big points…well, relatively speaking. (Magnavox, 1979)

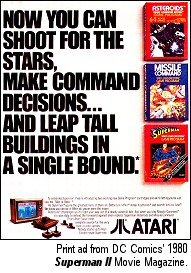

The Game: It’s all the thrills of pinball, minus approximately 75% of the excitement! Use your joystick to control the plunger tension and launch your ball into play. Use the action button to pop the flippers, keeping your ball on the field and out of trouble. The bumpers and spinner score big points…well, relatively speaking. (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a vaguely anthropomorphic heap o’ pixels with a red cape! Lex Luthor has hatched one of his deadly schemes to overthrow Metropolis – and, naturally, the world – starting with the destruction of a bridge in the city. Deal with Luthor’s thugs, save Lois, and put Lex himself behind bars – but keep an eye out for Kryptonite. (Atari [under license from DC Comics], 1979)

The Game: It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a vaguely anthropomorphic heap o’ pixels with a red cape! Lex Luthor has hatched one of his deadly schemes to overthrow Metropolis – and, naturally, the world – starting with the destruction of a bridge in the city. Deal with Luthor’s thugs, save Lois, and put Lex himself behind bars – but keep an eye out for Kryptonite. (Atari [under license from DC Comics], 1979)

The Game: As a lone space pilot flying down a seemingly endless trench, your job is simple – blast or bomb all of the vaguely-bow-tie-shaped space fighters that you see. If your fighter is on the lower half of the screen, you’re blasting straight ahead/upward; if you move your fighter near the top of the screen, you can bomb any fighters below you. The game ends when you run out of ships; fortunately you never seem to run out of ammo. (Bally, 1979)

The Game: As a lone space pilot flying down a seemingly endless trench, your job is simple – blast or bomb all of the vaguely-bow-tie-shaped space fighters that you see. If your fighter is on the lower half of the screen, you’re blasting straight ahead/upward; if you move your fighter near the top of the screen, you can bomb any fighters below you. The game ends when you run out of ships; fortunately you never seem to run out of ammo. (Bally, 1979) The Game: Get out there and draw! Your cowboy faces off against another player, or the computer, in a fight to see who can draw their gun the fastest – and who can run away the fastest! (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: Get out there and draw! Your cowboy faces off against another player, or the computer, in a fight to see who can draw their gun the fastest – and who can run away the fastest! (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: In a game that bears some slight resemblence to a Japanese offshoot of pinball, you control – for lack of a better description – a man stuck in a gigantic Pachinko playing field. You attempt to keep your ball in play, scoring points as often as possible by landing the ball in one of five cups marked with a point value – some targets can score zero points, others as high as ten. The other player – either a human being or the computer – can temporarily take over your ball by touching it, just as you can with theirs. (There’s nothing quite like making someone else’s balls work for you.) And a third man roams the playing field as well, grabbing your…well, let’s start that again. If the computer-controlled third man grabs a ball in mid-flight, he’ll relaunch it in a random direction, maybe to you, maybe to your opponent. Whoever accumulates 100 points first wins. (Magnavox, 1980)

The Game: In a game that bears some slight resemblence to a Japanese offshoot of pinball, you control – for lack of a better description – a man stuck in a gigantic Pachinko playing field. You attempt to keep your ball in play, scoring points as often as possible by landing the ball in one of five cups marked with a point value – some targets can score zero points, others as high as ten. The other player – either a human being or the computer – can temporarily take over your ball by touching it, just as you can with theirs. (There’s nothing quite like making someone else’s balls work for you.) And a third man roams the playing field as well, grabbing your…well, let’s start that again. If the computer-controlled third man grabs a ball in mid-flight, he’ll relaunch it in a random direction, maybe to you, maybe to your opponent. Whoever accumulates 100 points first wins. (Magnavox, 1980) The Game: In this two-for-one game, you take to the skies in one of two different ways. Out Of This World! is a classic lunar lander game, in which you must balance your descent speed and your remaining fuel to make a safe landing on the surface of the moon, and then safely return to dock with your command module in orbit again. Helicopter Rescue! is a simplistic game in which you pilot a helicopter, trying to retrieve as many people as possible from a doomed hotel and take them safely to a nearby ground station. Precision and timing are of the essence. (Honestly, though, we never see what’s wrong with that hotel – there’s no evidence of fire, terrorists, massive fiddygibber infestations…) (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: In this two-for-one game, you take to the skies in one of two different ways. Out Of This World! is a classic lunar lander game, in which you must balance your descent speed and your remaining fuel to make a safe landing on the surface of the moon, and then safely return to dock with your command module in orbit again. Helicopter Rescue! is a simplistic game in which you pilot a helicopter, trying to retrieve as many people as possible from a doomed hotel and take them safely to a nearby ground station. Precision and timing are of the essence. (Honestly, though, we never see what’s wrong with that hotel – there’s no evidence of fire, terrorists, massive fiddygibber infestations…) (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: Play ball! Two teams play until they each accumulate three “outs” per inning. Try to hit the ball out of the park, or confound the outfielders with a well-placed hit none of them can catch. Steal a base if you’re feeling really brave – and then try to cover your bases as best you can when the other player tries all of these same strategies on you. (Mattel Electronics, 1979)

The Game: Play ball! Two teams play until they each accumulate three “outs” per inning. Try to hit the ball out of the park, or confound the outfielders with a well-placed hit none of them can catch. Steal a base if you’re feeling really brave – and then try to cover your bases as best you can when the other player tries all of these same strategies on you. (Mattel Electronics, 1979) The Game: Two characters take up position on either side of two rotating clusters of numbers and symbols. A simple math problem or algebraic equation (nothing too fancy, usually just involving symbol or shape matching) appears in the bottom center of the screen, and you must guide your character to physically touch the appropriate number or symbol to correctly answer the problem. The first player to answer ten problems correctly wins the game (and, somewhat alarmingly, gets to watch his onscreen icon momentarily balloon to twice its normal size with an odd “explosion” sound). (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: Two characters take up position on either side of two rotating clusters of numbers and symbols. A simple math problem or algebraic equation (nothing too fancy, usually just involving symbol or shape matching) appears in the bottom center of the screen, and you must guide your character to physically touch the appropriate number or symbol to correctly answer the problem. The first player to answer ten problems correctly wins the game (and, somewhat alarmingly, gets to watch his onscreen icon momentarily balloon to twice its normal size with an odd “explosion” sound). (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: One of the earlier Odyssey2 space-related titles pits two players against a pair of pesky alien saucers. (It is theoretically possible to play this game solo, but it’s much more fun with two players, as many Odyssey games were.) The game play is almost simple: two planets, each with a system of four moons, orbit their way around the screen. The object of the game is to occupy the most territory by shooting the planets or moons until they change to the same color as your ship. The alien saucers, however, are also doing this, making life extremely difficult. They can also set their sights on you, destroying your ship. You can return to the fray if any planet or moon on the screen is the same color as your ship, but if the aliens blast that body before you’ve taken off again, you’re trapped until the next window of opportunity arises. (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: One of the earlier Odyssey2 space-related titles pits two players against a pair of pesky alien saucers. (It is theoretically possible to play this game solo, but it’s much more fun with two players, as many Odyssey games were.) The game play is almost simple: two planets, each with a system of four moons, orbit their way around the screen. The object of the game is to occupy the most territory by shooting the planets or moons until they change to the same color as your ship. The alien saucers, however, are also doing this, making life extremely difficult. They can also set their sights on you, destroying your ship. You can return to the fray if any planet or moon on the screen is the same color as your ship, but if the aliens blast that body before you’ve taken off again, you’re trapped until the next window of opportunity arises. (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: Purporting to be based on the ancient Chinese game of Go, Dynasty! is actually more of a variation of Othello. The same strategies apply, and can be played with two players, one against the computer, or – for those who are feeling a little bit lazy – the computer vs. itself. (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: Purporting to be based on the ancient Chinese game of Go, Dynasty! is actually more of a variation of Othello. The same strategies apply, and can be played with two players, one against the computer, or – for those who are feeling a little bit lazy – the computer vs. itself. (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: Take to the slopes, in a digital sort of way. Choose between the slalom, giant slalom and downhill events, get a partner on the other joystick, and plow through that white stuff like it’s gonna melt tomorrow. And try not to hit any of the obstacles – before you can even say “I want my two dollars!”*, a collision can send you into a tumble that’ll just carry you right into the next one…and the one after that…and the one after that… (Magnavox, 1979)

The Game: Take to the slopes, in a digital sort of way. Choose between the slalom, giant slalom and downhill events, get a partner on the other joystick, and plow through that white stuff like it’s gonna melt tomorrow. And try not to hit any of the obstacles – before you can even say “I want my two dollars!”*, a collision can send you into a tumble that’ll just carry you right into the next one…and the one after that…and the one after that… (Magnavox, 1979) The Game: Two armored knights coalesce out of thin air in an enclosed arena, swords at the ready. Before they can do battle, there’s the matter of simply navigating the arena’s geography: a pair of bottomless pits can lead either knight to his death, and each pit is surrounded on two sides by a staircase than can make for a handy resting place – or an even deadlier place to duel. There’s also a narrow catwalk between the pits. If the knights can stay on firm ground, the sword-swinging begins; when a knight is vanquished, he re-forms in the corner where he first appeared and can charge into battle again until he has lost all of his lives. Whoever’s still standing at the end of the game wins. (Cinematronics/Vectorbeam, 1979)

The Game: Two armored knights coalesce out of thin air in an enclosed arena, swords at the ready. Before they can do battle, there’s the matter of simply navigating the arena’s geography: a pair of bottomless pits can lead either knight to his death, and each pit is surrounded on two sides by a staircase than can make for a handy resting place – or an even deadlier place to duel. There’s also a narrow catwalk between the pits. If the knights can stay on firm ground, the sword-swinging begins; when a knight is vanquished, he re-forms in the corner where he first appeared and can charge into battle again until he has lost all of his lives. Whoever’s still standing at the end of the game wins. (Cinematronics/Vectorbeam, 1979) The Game: Pull the plunger back and fire the ball into play. The more bumpers it hits, the more points you rack up. But don’t let the ball leave the table – doing so three times ends the game. (Atari, 1979)

The Game: Pull the plunger back and fire the ball into play. The more bumpers it hits, the more points you rack up. But don’t let the ball leave the table – doing so three times ends the game. (Atari, 1979) The Game: This may sound awfully familiar, but you’re the lone surviving pilot of a space squadron decimated by enemy attacks. The enemy’s bow-tie-shaped fighters are closing in on you from all sides, and you must keep an eye on your own fighter’s shields, weapon temperature (overheated lasers don’t like to fire anymore), and ammo, all while trying to draw a bead on those pesky enemy ships. You’re also very much on your own – nobody’s going to show up and tell you you’re all clear, kid. (Exidy, 1979)

The Game: This may sound awfully familiar, but you’re the lone surviving pilot of a space squadron decimated by enemy attacks. The enemy’s bow-tie-shaped fighters are closing in on you from all sides, and you must keep an eye on your own fighter’s shields, weapon temperature (overheated lasers don’t like to fire anymore), and ammo, all while trying to draw a bead on those pesky enemy ships. You’re also very much on your own – nobody’s going to show up and tell you you’re all clear, kid. (Exidy, 1979) The Game: The player pilots a space fighter into an endless dogfight above a space station trench. Enemy ships attack from all directions, and even zip down the trench; and and all of these can be blasted into bits for points. Beware the fastest of these enemy fighters, which will appear with very little notice and fire directly at the player’s score, relieving it of points every time the fighter is successful with its attack! (Cinematronics, 1979)

The Game: The player pilots a space fighter into an endless dogfight above a space station trench. Enemy ships attack from all directions, and even zip down the trench; and and all of these can be blasted into bits for points. Beware the fastest of these enemy fighters, which will appear with very little notice and fire directly at the player’s score, relieving it of points every time the fighter is successful with its attack! (Cinematronics, 1979)