P.T. Barnum’s Acrobats!

The Game: You control an acrobat on a moving see-saw, launching your fellow acrobat into the air to pop balloons and defy gravity in an act that would’ve done old Barnum proud! But what goes up must come down, and your airborne acrobat, if he doesn’t bounce upward upon impact with more balloons, will plummet at alarming speed. You have to catch him with the empty end of the see-saw, thus catapulting the other acrobat into a fresh round of inflatible destruction. (North American Philips, 1982)

The Game: You control an acrobat on a moving see-saw, launching your fellow acrobat into the air to pop balloons and defy gravity in an act that would’ve done old Barnum proud! But what goes up must come down, and your airborne acrobat, if he doesn’t bounce upward upon impact with more balloons, will plummet at alarming speed. You have to catch him with the empty end of the see-saw, thus catapulting the other acrobat into a fresh round of inflatible destruction. (North American Philips, 1982)

Memories: Another variation on the timeless Breakout formula, this game represented one of the Odyssey2’s first ventures into an area which most other home video game systems had already entered: licensing.

Pooyan

The Game: You’re a mama pig trying to prevent her adorable piglets from becoming a side of bacon for a pack of big bad wolves. First, you try to shoot down as many wolves as they try to parachute to safety with balloons, and then you have to prevent them from rising back up again, because if they do, they’re going to push a big rock right off a cliff and on top of you. (Konami, 1982)

The Game: You’re a mama pig trying to prevent her adorable piglets from becoming a side of bacon for a pack of big bad wolves. First, you try to shoot down as many wolves as they try to parachute to safety with balloons, and then you have to prevent them from rising back up again, because if they do, they’re going to push a big rock right off a cliff and on top of you. (Konami, 1982)

Memories: For some unfathomable reason, the Atari 2600 cartridge of Pooyan is incredibly rare and valuable. Not that it isn’t a decent game, mind you; for Konami’s first entry into the home video game arena, Pooyan was a very good effort.

Pitfall!

The Game: As Pitfall Harry, you’re exploring the deepest jungle in search of legendary lost treasures, whether they be above ground, hidden strategically next to inescapable tar pits or ponds infested with hungry gators, or in the underground catacombs under the guard of deadly scorpions. (Activision, 1982)

The Game: As Pitfall Harry, you’re exploring the deepest jungle in search of legendary lost treasures, whether they be above ground, hidden strategically next to inescapable tar pits or ponds infested with hungry gators, or in the underground catacombs under the guard of deadly scorpions. (Activision, 1982)

Memories: Pitfall! – subtitled The Adventures of Pitfall Harry – was the first blockbuster title from Activision, a software house formed by four former Atari programmers. Activision consistently turned out addictively playable and – bearing in mind the 2600’s graphic limitations – gorgeous games. After all, Activision’s core gamesmiths knew the Atari 2600 hardware better than anyone, and were able to avoid such common, erm, pitfalls as flickering sprites and big, clunky pixels.

Pick Axe Pete!

The Game: As Pete, you start out in the center of a multi-tiered mine – not at the bottom – and your boulder-smashing pick axe begins to deteriorate after about one minute. Then you either have to jump over or duck under the onslaught of falling rocks, or you’re toast. Falling to the lower levels won’t kill you, if you time it just right so as not to land right in the middle of an avalanche. When two boulders collide, they can uncover treasures such as a fresh pick axe or, more importantly, a key to the next level. As you progress through the levels, one horizontal space is deleted somewhere on the screen at random, progressing on until you have a death-trap of open space where rocks can bounce right up into your face. (North American Philips, 1982)

The Game: As Pete, you start out in the center of a multi-tiered mine – not at the bottom – and your boulder-smashing pick axe begins to deteriorate after about one minute. Then you either have to jump over or duck under the onslaught of falling rocks, or you’re toast. Falling to the lower levels won’t kill you, if you time it just right so as not to land right in the middle of an avalanche. When two boulders collide, they can uncover treasures such as a fresh pick axe or, more importantly, a key to the next level. As you progress through the levels, one horizontal space is deleted somewhere on the screen at random, progressing on until you have a death-trap of open space where rocks can bounce right up into your face. (North American Philips, 1982)

Memories: As far as this gamer was concerned, Pick Axe Pete! was the greatest game ever created for the Odyssey 2. Far from your typical arcade adaptation, you can get further in this game by short stretches of furious action when you’ve got an axe to grind and then waiting patiently for the key to the next level to arrive.

Phoenix

The Game: In a heavily armed space fighter, your job is pretty simple – ward off wave after wave of bird-like advance fighters and Phoenix creatures until you get to the mothership, and then try to blow that to smithereens. All of which would be simple if not for the aliens’ unpredictable kamikaze dive-bombing patterns. The Phoenix creatures themselves are notoriously difficult to kill, requiring a direct hit in the center to destroy them – otherwise they’ll grow back whatever wings you managed to pick off of them and come back even stronger. (Atari, 1982)

The Game: In a heavily armed space fighter, your job is pretty simple – ward off wave after wave of bird-like advance fighters and Phoenix creatures until you get to the mothership, and then try to blow that to smithereens. All of which would be simple if not for the aliens’ unpredictable kamikaze dive-bombing patterns. The Phoenix creatures themselves are notoriously difficult to kill, requiring a direct hit in the center to destroy them – otherwise they’ll grow back whatever wings you managed to pick off of them and come back even stronger. (Atari, 1982)

Memories: A very good translation, this. Atari’s edition of Phoenix opted to skimp a little on the graphics of the arcade original (which, truthfully, weren’t that elaborate to begin with) and concentrated more on duplicating the maddeningly random attacks of the enemy birds from its coin-op forebear. The result is an extremely playable, addictive slice of the arcade right in your living room.

Phaser Patrol

The Game: The war between the humans and the spacefaring enemy Dracons isn’t going well, and you’ve enlisted to join the fight. In the cockpit of your space fighter, you toggle between your flight computer (where you can find and set a course for Dracon attack groups on the map, or helpful starbases where you can replenish and repair your ship) and the direct view ahead when you engage in combat. The Dracons throw a lot of firepower at you, but your own torpedoes have a longer “reach” than their ammo. Your ship can take a pounding in a firefight, gradually eliminating your shields, your targeting ability, and even your weapons. The game is over when you can’t withdraw for repairs and are destroyed by the Dracons. (Arcadia, 1982)

The Game: The war between the humans and the spacefaring enemy Dracons isn’t going well, and you’ve enlisted to join the fight. In the cockpit of your space fighter, you toggle between your flight computer (where you can find and set a course for Dracon attack groups on the map, or helpful starbases where you can replenish and repair your ship) and the direct view ahead when you engage in combat. The Dracons throw a lot of firepower at you, but your own torpedoes have a longer “reach” than their ammo. Your ship can take a pounding in a firefight, gradually eliminating your shields, your targeting ability, and even your weapons. The game is over when you can’t withdraw for repairs and are destroyed by the Dracons. (Arcadia, 1982)

The Game: In 1982, an assemblage of former Atari programmers, along with a few hand-picked rookie programmers, started their own third-party video game venture. To be in that market at that time, however, one had to make games for the Atari 2600, and the Arcadia programmers’ game concepts outstripped that machine’s software. Not to be slowed down by that minor problem, Arcadia introduced a new piece of hardware along with its first game. The Supercharger more than doubled the 2600’s RAM, and had the beneficial side effect of allowing Arcadia to avoid the costly practice of having cartridge casings made; instead of cartridges, the Supercharger loaded its enhanced games from cassette tape, usually in under 30 seconds.

Pac-Man

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. (Atari, 1982)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period. (Atari, 1982)

Memories: It all began with the arrival of the Pac-Man arcade game in 1980. Pac-Man was guzzling millions of quarters and generating a licensing and merchandising firestorm. Numerous home video game companies bid for the rights to the game, and you have to understand, bidding for the rights to produce the home video game version of Pac-Man was like bidding for the toy rights for the next Star Wars movie – very expensive and very high-profile. Money was flying fast and furious. Atari won.

Pac-Man

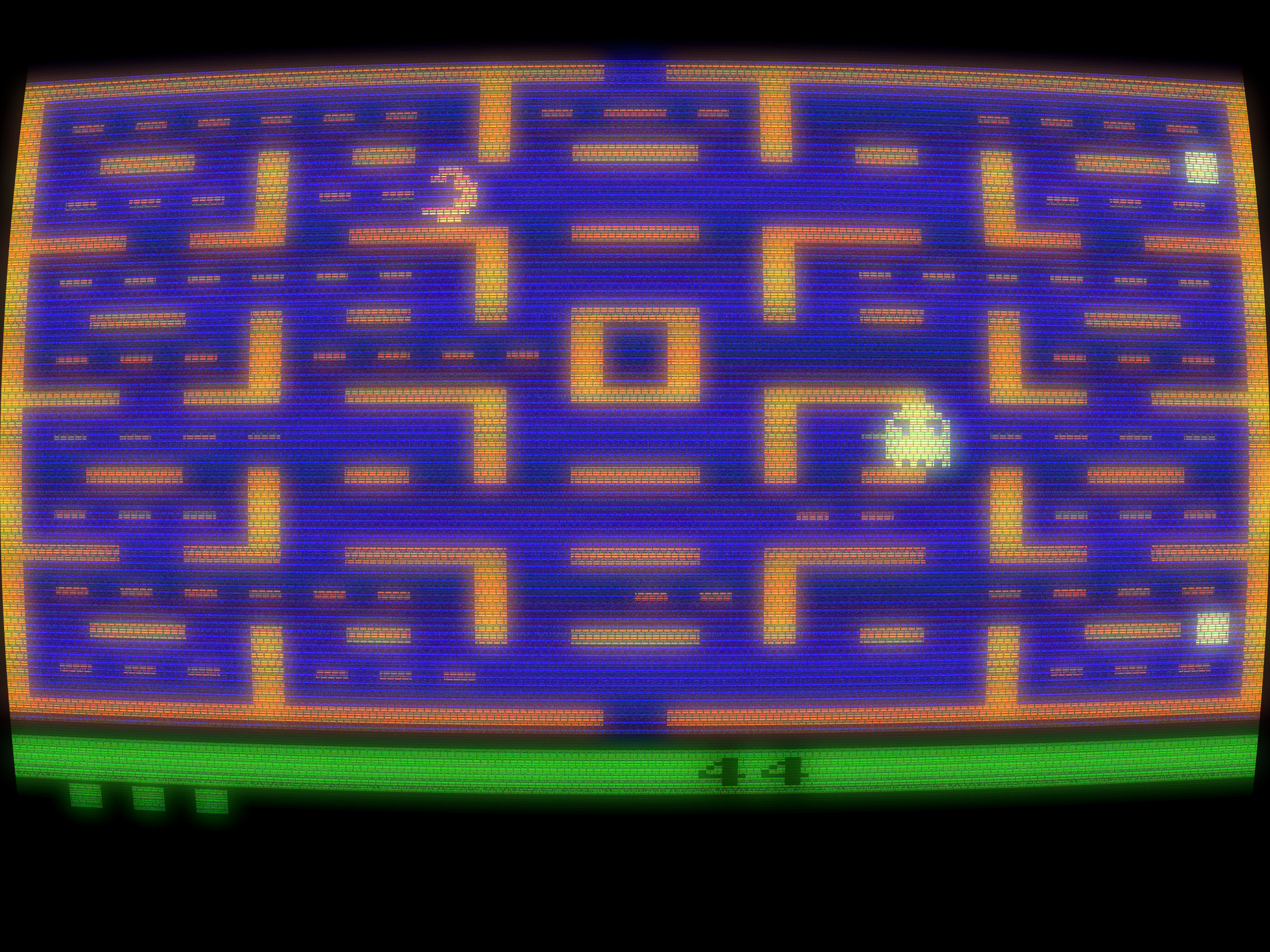

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score . Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Atari, 1982)

The Game: As a round yellow creature consisting of a mouth and nothing else, you maneuver around a relatively simple maze, gobbling small dots and evading four colorful monsters who can eat you on contact. In four corners of the screen, large flashing dots enable you to turn the tables and eat the monsters for a brief period for an escalating score . Periodically, assorted items appear near the center of the maze, and you can consume these for additional points as well. The monsters, once eaten, return to their home base in ghost form and return to chase you anew. If cleared of dots, the maze refills and the game starts again, but just a little bit faster… (Atari, 1982)

Memories: In the war of the second-generation consoles, it was clear what the chief ammunition would be: immensely popular arcade game licenses. The ColecoVision jumped out of the gates with Donkey Kong as a pack-in title, and Atari – already fighting bad word-of-mouth criticism of the 5200’s lackluster joysticks – would have to give the SuperSystem something a little more compelling than its cousin 2600’s Combat pack-in. But then, of course, everyone already knew that Atari held that most precious of arcade licenses in the early 80s, Pac-Man.

Omega Race

The Game: In an enclosed track in space, you pilot a sleek, lone space fighter up against an army of mine-laying opponents. In early rounds of the Omega Race, only a few minelayers activate at a time…but in later rounds, they all deploy their full arsenal at you at once, leaving you to dodge through a deadly maze in zero gravity while trying to turn to draw a bead on your opponents. You can bounce off of the walls of the track, but anything else is deadly to touch. (CBS Electronics, under license from Bally/Midway, 1982)

The Game: In an enclosed track in space, you pilot a sleek, lone space fighter up against an army of mine-laying opponents. In early rounds of the Omega Race, only a few minelayers activate at a time…but in later rounds, they all deploy their full arsenal at you at once, leaving you to dodge through a deadly maze in zero gravity while trying to turn to draw a bead on your opponents. You can bounce off of the walls of the track, but anything else is deadly to touch. (CBS Electronics, under license from Bally/Midway, 1982)

Memories: Cashing in on Omega Race‘s cult following in arcades – it was Midway‘s direct response to the Newtonian physics of Atari‘s Asteroids – CBS gave its home version of Omega Race the dubious distinction of being playable only with the included Booster Grip joystick “enhancer” – and as many second-hand copies of Omega Race have circulated on the collectors’ market without the Booster Grip, some gamers have been scratching their heads in bewilderment.

Pepper II

The Game: You’re a little angel (of sorts). You run around a maze consisting of zippers which close or open, depending upon whether or not you’ve already gone over that section of the maze. Zipping up one square of the maze scores points for you, but it gets trickier. Little devils chase you around the maze, trying to kill you before you can zip up the entire screen. If you zip up enough of the maze and grab a power-pellet-like object, you can dispatch some of your pursuers. Clear the screen and the fun begins anew. (Exidy, 1982)

The Game: You’re a little angel (of sorts). You run around a maze consisting of zippers which close or open, depending upon whether or not you’ve already gone over that section of the maze. Zipping up one square of the maze scores points for you, but it gets trickier. Little devils chase you around the maze, trying to kill you before you can zip up the entire screen. If you zip up enough of the maze and grab a power-pellet-like object, you can dispatch some of your pursuers. Clear the screen and the fun begins anew. (Exidy, 1982)

Memories: One of the first games released for Colecovision, Pepper II lived up to the advertising hype that basically said that owning Coleco’s new console was as good as having your own arcade. While the original arcade game didn’t exactly set the bar very high for any home adaptations, Pepper II really sells the Colecovision = arcade message by being almost flawless.

Night Stalker

The Game: You’re alone, unarmed, in a maze full of bats, bugs and ‘bots, most of whom can kill you on contact (though the robots would happily shoot you rather than catching up with you). Loaded guns appear periodically, giving you a limited number of rounds with which to take out some of these creepy foes, though your shots are best reserved for the robots and the spiders, who have a slightly more malicious intent toward you than the bats. If you shoot the bats, others will appear to take their place. If you shoot the ‘bots, the same thing happens, only a faster, sharper-shooting model rolls out every time. Your best bet is to stay on the move, stay armed, conserve your firepower – and don’t be afraid to head back to your safe room at the center of the screen. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

The Game: You’re alone, unarmed, in a maze full of bats, bugs and ‘bots, most of whom can kill you on contact (though the robots would happily shoot you rather than catching up with you). Loaded guns appear periodically, giving you a limited number of rounds with which to take out some of these creepy foes, though your shots are best reserved for the robots and the spiders, who have a slightly more malicious intent toward you than the bats. If you shoot the bats, others will appear to take their place. If you shoot the ‘bots, the same thing happens, only a faster, sharper-shooting model rolls out every time. Your best bet is to stay on the move, stay armed, conserve your firepower – and don’t be afraid to head back to your safe room at the center of the screen. (Mattel Electronics, 1982)

Memories: A devious and nerve-wracking little maze chase of a game, Night Stalker is a great game if you’re up for an endurance contest, but not so much if you’re looking for a game where you actually stand a chance of winning or advancing to a new maze. The playing field you see is the playing field you get, and you’re stuck there – until you die.

Nimble Numbers NED!

The Game: You are NED, hopping over boulders and, with each obstacle overcome, tackling progressively more difficult math questions and pattern-matching exercises. You can select what kind of math you need to work on (addition, subtraction, etc.), and if you don’t solve a problem correctly the first time, it’s broken down into smaller parts to help you work out how it all goes together. (North American Philips, 1982)

The Game: You are NED, hopping over boulders and, with each obstacle overcome, tackling progressively more difficult math questions and pattern-matching exercises. You can select what kind of math you need to work on (addition, subtraction, etc.), and if you don’t solve a problem correctly the first time, it’s broken down into smaller parts to help you work out how it all goes together. (North American Philips, 1982)

Memories: This game was originally going to be called Math Potatoes! – and as inauspicious a title as Nimble Numbers NED! may be, you have to admit that Math Potatoes! probably would’ve been too bizarre to entice parents looking for suitable educational software for their kids.

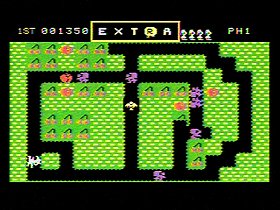

Mr. Do!

The Game: As an elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up

The Game: As an elfin dweller of a magic garden, you must avoid or do away with a bunch of nasty critters who are after you, while gobbling up  as much yummy fruit as you can. (Coleco, 1982)

as much yummy fruit as you can. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: Probably the highest-profile title of Coleco’s original licensing deal with Universal, Mr. Do! came home in an almost insanely entertaining cartridge for the ColecoVision. The graphics and sound closely mimic those of the arcade game, and control seems fairly smooth to me.

Mouse Trap

The Game: In this munching-maze game (one of the dozens of such games which popped up in the wake of Pac-Man), you control a cartoonish mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing doors in the maze. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone (the equivalent of Pac-Man’s power pellets), you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: In this munching-maze game (one of the dozens of such games which popped up in the wake of Pac-Man), you control a cartoonish mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing doors in the maze. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone (the equivalent of Pac-Man’s power pellets), you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: To some extent, I think regular readers of Phosphor Dot Fossils have come to expect certain things…and the occasional justified slamming of a 2600 game or two is probably one of them. But not this one. No, I’m here to tell you that I love Coleco’s 2600 translation of the obscure Exidy coin-op maze chase Mouse Trap. Yes, seriously!

Mouse Trap

The Game: In this munching-maze game, you control a mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing yellow, red and blue doors with their color-coded buttons. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone, you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: In this munching-maze game, you control a mouse who scurries around a cheese-filled maze which can only be navigated by strategically opening and closing yellow, red and blue doors with their color-coded buttons. Occasionally a big chunk o’ cheese can be gobbled for extra points. Is it that easy? No. There is also a herd of hungry kitties who would love a mousy morsel. But you’re not defenseless. By eating a bone, you can transform into a dog, capable of eating the cats. But each bone’s effects only last for a little while, after which you revert to a defenseless mouse. (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: Based on the almost-obscure Exidy arcade game, Coleco turned out a faithful cartridge version of Mouse Trap, with one drawback – just as it was in the arcade, the control scheme for opening the color-coded doors throughout the maze wasn’t the most intuitive way that anyone had ever come up with for controlling a game, even if one does have the overlays that fit over the controller keypads.

Moonsweeper

The Game: As the pilot of a super-fast intergalactic rescue ship (which is also armed to the teeth, which explains the absence of a red cross painted on the hull), you must navigate your way through hazardous comets and space debris, entering low orbit around various planets from which you must rescue a certain number of stranded civilians. But there’s a reason you’re armed – some alien thugs mean to keep those people stranded, and will do their best to blast you into dust. You can return the favor, and after you rescue the needed quota of people from the surface, you must align your ship with a series of launch rings to reach orbit again. (Imagic, 1982)

The Game: As the pilot of a super-fast intergalactic rescue ship (which is also armed to the teeth, which explains the absence of a red cross painted on the hull), you must navigate your way through hazardous comets and space debris, entering low orbit around various planets from which you must rescue a certain number of stranded civilians. But there’s a reason you’re armed – some alien thugs mean to keep those people stranded, and will do their best to blast you into dust. You can return the favor, and after you rescue the needed quota of people from the surface, you must align your ship with a series of launch rings to reach orbit again. (Imagic, 1982)

Memories: The coolest Imagic game ever, Moonsweeper kept my attention for hours and hours, just trying to beat the bloody thing.

Microsurgeon

The Game: Ready for a fantastic journey? So long as you’re not counting on Raquel Welch riding shotgun with you, this is as close as you’re going to get. You control a tiny robot probe inside the body of a living, breathing human patient who has a lot of health problems. Tar deposits in the lungs, cholesterol clogging the arteries, and rogue infections traveling around messing everything up. And then there’s you – capable of administering targeted doses of ultrasonic sound, antibiotics and aspirin to fix things up. Keep an eye on your patient’s status at all times – and be careful not to wipe out disease-fighting white blood cells which occasionally regard your robot probe as a foreign body and attack it. Just because you don’t get to play doctor with the aforementioned Ms. Welch (ahem – get your mind out of the gutter!) doesn’t mean this won’t be a fun operation. (Imagic, 1982)

The Game: Ready for a fantastic journey? So long as you’re not counting on Raquel Welch riding shotgun with you, this is as close as you’re going to get. You control a tiny robot probe inside the body of a living, breathing human patient who has a lot of health problems. Tar deposits in the lungs, cholesterol clogging the arteries, and rogue infections traveling around messing everything up. And then there’s you – capable of administering targeted doses of ultrasonic sound, antibiotics and aspirin to fix things up. Keep an eye on your patient’s status at all times – and be careful not to wipe out disease-fighting white blood cells which occasionally regard your robot probe as a foreign body and attack it. Just because you don’t get to play doctor with the aforementioned Ms. Welch (ahem – get your mind out of the gutter!) doesn’t mean this won’t be a fun operation. (Imagic, 1982)

Memories: Microsurgeon, designed and programmed by Imagic code wrangler Rick Levine (who even put his signature – as a series of slightly twisted arteries – inside the game’s human body maze), is a perfect example of Imagic’s ability to get the best out of the Intellivision – it’s truly one of those “killer app” games that defines a console.

Mine Storm

The Game: An alien ship zooms into view overhead, depositing a network of mines in deep space. Your job is to clear the spaceways, blasting each mine and then blasting the smaller mines that are released by each subsequent explosion; there are three different mine sizes, and blasting the smallest and fastest ones finally does away with them. In later stages, there are homing mines, mines that launch a missile in your direction when detonated, and other hazards. Smaller alien ships periodically zip through the screen, trying to blast you while also laying fresh mines. (GCE, 1982)

The Game: An alien ship zooms into view overhead, depositing a network of mines in deep space. Your job is to clear the spaceways, blasting each mine and then blasting the smaller mines that are released by each subsequent explosion; there are three different mine sizes, and blasting the smallest and fastest ones finally does away with them. In later stages, there are homing mines, mines that launch a missile in your direction when detonated, and other hazards. Smaller alien ships periodically zip through the screen, trying to blast you while also laying fresh mines. (GCE, 1982)

Memories: Obviously the Vectrex answer to Asteroids, Mine Storm wins about a zillion bonus points just for being drawn in honest-to-God vector graphics – and for being built in to the Vectrex’s circuitry. If you power the machine up without a cartridge plugged in, you get Mine Storm, and it’s a gem of a game.

Megamania

The Game: The sky is falling! Or so it seems. As this game is subtitled “A Space Nightmare,” you’re not battling aliens here, but ever-descendig and evading waves of such ordinary items as bow ties, hamburgers, dice, and so on. Unlike so many other Space Invaders variations, you won’t die the moment the attacking forces reach ground zero – but you could, if they slide horizontally right into you. (Activision, 1982)

The Game: The sky is falling! Or so it seems. As this game is subtitled “A Space Nightmare,” you’re not battling aliens here, but ever-descendig and evading waves of such ordinary items as bow ties, hamburgers, dice, and so on. Unlike so many other Space Invaders variations, you won’t die the moment the attacking forces reach ground zero – but you could, if they slide horizontally right into you. (Activision, 1982)

Memories: Activision, much like the Odyssey 2 game designers, always knew how to put enough of a twist on game with an established “formula” to keep the litigious wolf from the door, and this is another classic example of that – not to mention an annoyingly addictive little game.

Math Gran Prix

The Game: This race is a numbers game. For each turn, players have to decide how many spaces they want to move (overdoing it can result in going off-track and crashing), and then have to answer a math question (math functions and difficulty depend on game settings). Answering correctly will allow the player to move forward the desired number of spaces. A few spots on the track offer the chance to pick a random number for an additional jump forward in the race. (Atari, 1982)

The Game: This race is a numbers game. For each turn, players have to decide how many spaces they want to move (overdoing it can result in going off-track and crashing), and then have to answer a math question (math functions and difficulty depend on game settings). Answering correctly will allow the player to move forward the desired number of spaces. A few spots on the track offer the chance to pick a random number for an additional jump forward in the race. (Atari, 1982)

Memories: Few equations have proven as impossible in the video game industry as the still-ongoing quest to make educational games not just fun, but something that anyone would actually want to fork over money for and play. Hint: Math Gran Prix, despite its noble intentions, did not solve that equation.

Loco Motion

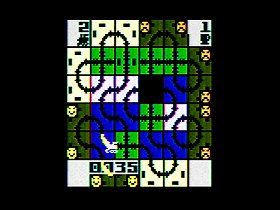

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. You can move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Mattel [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: A train scoots around a twisty maze of tiles representing overpasses, turns, straightaways and terminals. One portion of the maze is blank, and a train will be lost if it hits that blank tile. You can move the blank tile and one adjacent tile around on the map – even if the train is in transit on that tile – in an effort to keep it moving around the maze, picking up passengers. (Passengers that the train can reach are smiley faces; passengers cut off from the main route are frowning.) If any passengers are cut off for an extended period of time, a monster begins wandering that route, and it’ll cost you a train if it comes in contact with your train. You may have to outrun it with the “speed” button in order to pick up the last passengers and clear the level to move on to a bigger maze. (Mattel [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: Mattel’s licensed adaptation of the extremely minor arcade hit by Konami is actually, believe it or not, an improvement in some areas on the arcade game. The graphic look isn’t one of those areas, but in a strange way, the Intellivision’s disc controller is more instinctive for the sliding-tile-puzzle game play of Loco Motion.

Lost Luggage

The Game: Before the TSA, there was… a little pixellated stick man on your Atari. Using the joysticks, your job is to direct this hapless less line of airport defense to catch every piece of luggage before it hits the sides or bottom of the screen. Failure to do so will result in the contents of the luggage spilling out across the floor; on some difficulty settings, black suitcases appear containing explosives that’ll detonate if that case isn’t caught. As soon as the area is successfully cleared of luggage, there’s a moment to catch your breath before the next plane lands and the process begins again. (Games By Apollo, 1982)

The Game: Before the TSA, there was… a little pixellated stick man on your Atari. Using the joysticks, your job is to direct this hapless less line of airport defense to catch every piece of luggage before it hits the sides or bottom of the screen. Failure to do so will result in the contents of the luggage spilling out across the floor; on some difficulty settings, black suitcases appear containing explosives that’ll detonate if that case isn’t caught. As soon as the area is successfully cleared of luggage, there’s a moment to catch your breath before the next plane lands and the process begins again. (Games By Apollo, 1982)

Memories: As funny as the game’s programmer thought it’d be to stick bombs in his pixellated suitcases on certain settings, Lost Luggage is one of those games that means something completely different now than it did at the time of release. But unintentionally prophetic dark humor or not, it’s one of the better catch-everything-or-else games on the VCS.

Lock ‘n’ Chase

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak the crooks around the maze, one at a time, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. (Mattel [under license from Data East], 1982)

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak the crooks around the maze, one at a time, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. (Mattel [under license from Data East], 1982)

Memories: A fine translation of Data East’s arcade game, this cartridge – one of the earliest examples of a licensed coin-op title from Mattel – is let down by the maddening control problems of the dreaded disc controller. But audiovisually speaking, it was as close as one could get to the original, so I do have to award it some points there.

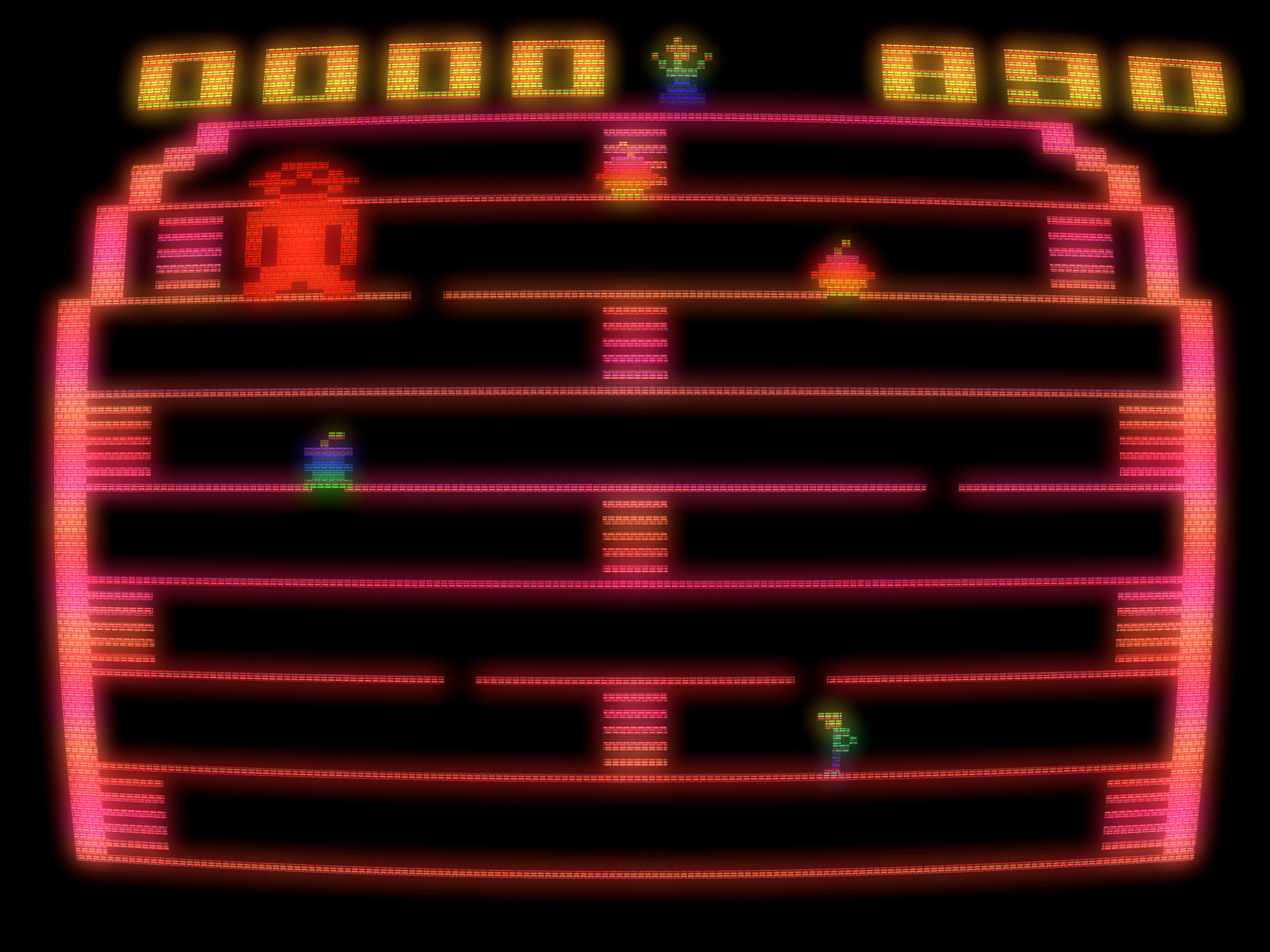

Lock ‘N’ Chase

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak around the maze, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. But the cops can trap you with a series of doors that can prevent you from getting away… (M Network [Mattel Electronics], 1982)

The Game: You’re in charge of a getaway car loaded with crafty criminals. Your job is to sneak around the maze, avoid four colorful cops who are hot on your trail, and grab all the dough – and, of course, to escape so you can steal again another day. But the cops can trap you with a series of doors that can prevent you from getting away… (M Network [Mattel Electronics], 1982)

Memories: 1982. The year that everybody – and I do mean everybody – was trying to build a better Pac-Man. Mattel’s Intellivision console was suffering from the perception among mainstream gamers that the new, next-generation machine lacked arcade titles in its library; with titles like Major League Baseball, Mattel owned the video sports market. But this was 1982 and America had yet to sweat off Pac-Man Fever – sports games weren’t “in” at the moment.

Ladybug

The Game: You’re a hungry ladybug in a maze full of dangers and morsels. Other insects roam the maze trying to eat you, and skulls scattered around the maze are also deadly to the touch. The only advantage you really have is to maneuver skillfully through the revolving doors, slamming them shut behind you and forcing your pursuers to take a different route (they can’t go through the revolving doors). (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: You’re a hungry ladybug in a maze full of dangers and morsels. Other insects roam the maze trying to eat you, and skulls scattered around the maze are also deadly to the touch. The only advantage you really have is to maneuver skillfully through the revolving doors, slamming them shut behind you and forcing your pursuers to take a different route (they can’t go through the revolving doors). (Coleco, 1982)

Memories: With the rights to mega-hits like Pac-Man taken by the time the ColecoVision hit the stores, Coleco grabbed the rights to a number of somewhat more obscure arcade games, including virtually the entire catalog of Universal games, the makers of such games as Mr. Do, Mr. Do’s Castle, and Ladybug. Coleco’s Ladybug cartridge is a very faithful rendition of its arcade inspiration, and it’s quite a bit of fun.

King Kong

The Game: In a stick-figure firefighter’s greatest adventure, you have to help him reach the top of a perilous scaffolding to rescue a damsel in distress from the dastardly Kong Kong. (Tiger Electronic Toys, 1982)

The Game: In a stick-figure firefighter’s greatest adventure, you have to help him reach the top of a perilous scaffolding to rescue a damsel in distress from the dastardly Kong Kong. (Tiger Electronic Toys, 1982)

Memories: Just when you thought no one could make a worse Atari 2600 Donkey Kong than Coleco could, the electronics division of Tiger Toys comes along and demonstrates that yes, it could have easily been worse. In fact, that this game even made it to the stores after initially being rejected is just a small part of a much more convoluted legal saga.

Keystone Kapers

The Game: Kriminals are on the loose in an unspecified retail establishment, and you happen to be the lone kop on the kase. Bouncy balls, shopping karts and other krap get in your way as you try to katch the kriminal before time runs out. You might get lucky and hitch an elevator ride, or you may have to take the escalators at opposite ends of the store, which will take more time. If you don’t kapture the krook, he gets away with the loot. (Activision, 1982)

The Game: Kriminals are on the loose in an unspecified retail establishment, and you happen to be the lone kop on the kase. Bouncy balls, shopping karts and other krap get in your way as you try to katch the kriminal before time runs out. You might get lucky and hitch an elevator ride, or you may have to take the escalators at opposite ends of the store, which will take more time. If you don’t kapture the krook, he gets away with the loot. (Activision, 1982)

Memories: A simple little game from the hallowed house of Activision, Keystone Kapers is one of those games you really don’t need the docs to play.

K.C.’s Krazy Chase

The Game: As a small blue spherical creature whose sole sensory organs consist of two eyes, two antennae and an enormous mouth, your mission – should you choose to accept it – is to start munching on the segmented body of the dreaded Dratapillar while avoiding its always-lethal head. When you consume one of its body segments, the Dratapillar’s two henchbeings – known only as Drats – turn white with fright and you can send them a-spinning (normally, they’re deadly to touch too). Eating all of the Dratapillar segments gets you to the next level, and the mayhem begins anew. (North American Philips, 1982)

The Game: As a small blue spherical creature whose sole sensory organs consist of two eyes, two antennae and an enormous mouth, your mission – should you choose to accept it – is to start munching on the segmented body of the dreaded Dratapillar while avoiding its always-lethal head. When you consume one of its body segments, the Dratapillar’s two henchbeings – known only as Drats – turn white with fright and you can send them a-spinning (normally, they’re deadly to touch too). Eating all of the Dratapillar segments gets you to the next level, and the mayhem begins anew. (North American Philips, 1982)

Memories: Perhaps just out of spite, the first non-educational game released to take advantage of the Odyssey 2’s new Voice add-on module featured K.C. Munchkin, the Pac-Man-esque critter who had landed Magnavox on the wrong side of a look-and-feel software lawsuit filed by Atari.

Jungler

The Game: Players control a segmented, centipede-like creature as it wanders through an open maze inhabited by similar creatures. The player’s creature can shoot segments off of the opponent creatures, but the opponents can also turn around and eat their own segments to get out of a corner, which won’t score any points for the player. To clear a level, the player must eliminate the other creatures from the maze. (Emerson [under license from Konami], 1982)

The Game: Players control a segmented, centipede-like creature as it wanders through an open maze inhabited by similar creatures. The player’s creature can shoot segments off of the opponent creatures, but the opponents can also turn around and eat their own segments to get out of a corner, which won’t score any points for the player. To clear a level, the player must eliminate the other creatures from the maze. (Emerson [under license from Konami], 1982)

Memories: 1982 had the dubious distinction of being both the peak year for video gaming, and – arguably – the beginning of the end. That end didn’t play out until the industry crash of 1983 and ’84, but the seeds were planted at least as early as 1982, when the arcade license ruled the home video game roost. Even modest or completely unknown games could command top dollar for home console ports, often in advance of their arcade release, just on the off chance that the licensee was hitching its wagon to the next Pac-Man. Hence… Nibbler.

Jin

The Game: The player controls a marker, trying to claim as much of the playing field as possible by enclosing areas of it. Drawing boundaries faster is safer, but yields fewer points. A slower draw, which leaves the marker vulnerable to attack from the Jin and from the enemies in hot pursuit of the marker’s every move, is worth many more points upon the completion of an enclosed area. If the ever-shifting Jin touches the marker or an uncompleted boundary it is drawing, a “life” is lost and the game starts again. (Falcon, 1982)

The Game: The player controls a marker, trying to claim as much of the playing field as possible by enclosing areas of it. Drawing boundaries faster is safer, but yields fewer points. A slower draw, which leaves the marker vulnerable to attack from the Jin and from the enemies in hot pursuit of the marker’s every move, is worth many more points upon the completion of an enclosed area. If the ever-shifting Jin touches the marker or an uncompleted boundary it is drawing, a “life” is lost and the game starts again. (Falcon, 1982)

Memories: Not content merely to copy Donkey Kong in the form of Crazy Kong (though that game was actually Nintendo-licensed for distribution in Far East markets outside Japan, and never intended to wind up in North America, though it did anyway), bootleg maker Falcon diversified its offerings by copying another Japanese game maker, unapologetically turning Taito‘s Qix into Jin. But for some bizarre reason, Falcon used a different game’s hardware to do this.