Colecovision

Not far into the early 80’s home video game boom, Coleco – the shortened name of the Connecticut Leather Company, which had gotten into the toy and game business with such products as air hockey tables and minor sporting equipment – was already a player, having snagged some of the biggest arcade game licenses for translation into tabletop games with colorful arcade marquees and cabinet art (miniaturized, of course) and glowing LED screens. But Coleco also seized a golden opportunity by creating the high-end ColecoVision system, probably the most advanced home video game platform available through 1983, and continuing to license popular games from Nintendo and Sega – neither of which, at the time, had created their own home video game systems (almost unthinkable now, isn’t it?).

Not far into the early 80’s home video game boom, Coleco – the shortened name of the Connecticut Leather Company, which had gotten into the toy and game business with such products as air hockey tables and minor sporting equipment – was already a player, having snagged some of the biggest arcade game licenses for translation into tabletop games with colorful arcade marquees and cabinet art (miniaturized, of course) and glowing LED screens. But Coleco also seized a golden opportunity by creating the high-end ColecoVision system, probably the most advanced home video game platform available through 1983, and continuing to license popular games from Nintendo and Sega – neither of which, at the time, had created their own home video game systems (almost unthinkable now, isn’t it?).

Coleco did things right. Where the Atari 5200 offered no compensation to consumers that – hopefully – would step up from the Atari 2600, one of the earliest ColecoVision peripherals was an adapter that would allow Atari 2600 games to be played on this new system, making Coleco a shoe-in for 2600 owners seeking an upgrade. ColecoVision also appeared just in time to take advantage of another crowd of Atari 2600 users – those who were disgruntled with some of the

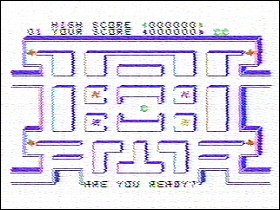

Coleco did things right. Where the Atari 5200 offered no compensation to consumers that – hopefully – would step up from the Atari 2600, one of the earliest ColecoVision peripherals was an adapter that would allow Atari 2600 games to be played on this new system, making Coleco a shoe-in for 2600 owners seeking an upgrade. ColecoVision also appeared just in time to take advantage of another crowd of Atari 2600 users – those who were disgruntled with some of the  more pathetic Atari 2600 cartridges on the market (namely Pac-Man). With these two factors working for it, ColecoVision gained a much wider audience than Atari’s 5200.

more pathetic Atari 2600 cartridges on the market (namely Pac-Man). With these two factors working for it, ColecoVision gained a much wider audience than Atari’s 5200.

Though later attempts to add to the ColecoVision legacy capsized – namely the ColecoVision-compatible ADAM home computer – and though Coleco itself eventually went out of business, this is one of the more fondly remembered home video game systems.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=256]

Atari 5200 SuperSystem

Not long after the Atari 2600 debuted, Atari tried to extend its market dominance into the home computer market with the Atari 400 and Atari 800, home computers with, respectively, 16k and 48k of RAM, the ability to add disk drives and modems, and more. But at the heart of both machines was the same industry that had made Atari a household name to begin with – both of Atari’s computers required RF connectors to use a TV as a display, and both had cartridge slots for games.

Not long after the Atari 2600 debuted, Atari tried to extend its market dominance into the home computer market with the Atari 400 and Atari 800, home computers with, respectively, 16k and 48k of RAM, the ability to add disk drives and modems, and more. But at the heart of both machines was the same industry that had made Atari a household name to begin with – both of Atari’s computers required RF connectors to use a TV as a display, and both had cartridge slots for games.

After failing to set the young home computer market on fire – at that time, Apple and IBM had already conquered the world with the Apple IIe and the original PC – Atari took its computers’

After failing to set the young home computer market on fire – at that time, Apple and IBM had already conquered the world with the Apple IIe and the original PC – Atari took its computers’  processors, put them in a keyboard-less casing, repackaged the cartridges, and created the Atari 5200 – rather more expensive than the Atari 2600, but capable of coming much closer to emulating everyone’s favorite arcade games.

processors, put them in a keyboard-less casing, repackaged the cartridges, and created the Atari 5200 – rather more expensive than the Atari 2600, but capable of coming much closer to emulating everyone’s favorite arcade games.

It’s easy to criticize Atari for making the 5200 unit completely incompatible with the far more prolific Atari 2600 – and more to the point, incompatible with most 2600 owners’ growing collection of cartridges which would be useless with a new platform – and this made the Atari 5200 strictly a high-end luxury niche platform with a small audience. By the time they wised up and put a 2600 Adapter on the shelves, it was too late.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=15]

- Hardware review: Wico Command Control Joystick & Keypad

Vectrex

In the early days of the arcade, there were two approaches to graphics – raster (like a traditional TV or computer display), which was driven by processors that offered color but not very good resolution, or vector, also known as X/Y graphics. Raster TV displays work by using a series of “guns” to fire electrons at a screen; to fill the entire screen, the display constantly scans and redraws every horizontal line of the picture. X/Y displays drew only what they needed to: the guns in an X/Y display would fire an intense beam of electrons only at those portions of the screen that required something to be drawn, resulting in a very sharp, very bright display, but one which left plenty of “black” space. At first vector graphics were strictly black & white, though later innovations brought color to vector displays, though usually at the cost of equipment that would run hot and break down easily. Vector graphics drove medical displays for years before gamers became familiar with vector as the kind of display that drove games like Asteroids, Warrior, Tempest, Star Wars and Omega Race.

In the early days of the arcade, there were two approaches to graphics – raster (like a traditional TV or computer display), which was driven by processors that offered color but not very good resolution, or vector, also known as X/Y graphics. Raster TV displays work by using a series of “guns” to fire electrons at a screen; to fill the entire screen, the display constantly scans and redraws every horizontal line of the picture. X/Y displays drew only what they needed to: the guns in an X/Y display would fire an intense beam of electrons only at those portions of the screen that required something to be drawn, resulting in a very sharp, very bright display, but one which left plenty of “black” space. At first vector graphics were strictly black & white, though later innovations brought color to vector displays, though usually at the cost of equipment that would run hot and break down easily. Vector graphics drove medical displays for years before gamers became familiar with vector as the kind of display that drove games like Asteroids, Warrior, Tempest, Star Wars and Omega Race.

Vector graphics games were incredibly hard to translate to home consoles, since even the most advanced consoles were generally considered to have rather chunky graphics. (Some attempted translations were so clumsy, in fact, that there were abandoned before ever hitting the market – such as Atari’s version of its hit game Tempest for the Atari 2600.) GCE engineer Jay Smith had an idea, however – if you couldn’t bring vector graphics home without an X/Y monitor, then why not bring the monitor home? Together with his team at CGE, Smith devised the Vectrex, a stand-alone game system which, while pricey, would delight mom and dad by freeing up the TV. Among video game fans circa 1982, Vectrex was the ultimate status symbol – it was a little arcade game unto itself, but with cartridges that would let its owners play different games. Even now, a working Vectrex is still one of the high points of any classic video game collection.

As enthusiastic about Vectrex as game players were, game makers were too. Cinematronics, one of the companies that pioneered vector games, licensed games like Star Castle for the first time. The makers of Berzerk, Stern, licensed that game even though a similar license had already been granted to Atari. And Milton Bradley, the board and card game giant that had only put out the most tentative feelers in the video game industry, saw Vectrex as the future of that industry and bought the company to bring the system (and its future profits) under its wing.

Vectrex, however, shared one drawback with its arcade cousins: the machine generated only black & white graphics on its 9-inch vector monitor. Built into the monitor housing were tabs that held sturdy, colorful transparent overlays in place to create the illusion of spot color, a trick that hadn’t been used since the days of the Magnavox Odyssey. But at the same time, Jay Smith and his team were quietly working on a color version of Vectrex, and they constructed at least one working prototype.

But time ran out for Vectrex, as it did for every other system in the early 1980s with the video game industry crash that leveled the playing field and drove many of the players out of business – or at least out of the industry and back into the business of making more traditional toys, games or computers. Yet even without the crash, Vectrex was a system living on borrowed time, as vector graphics fell out of favor with arcade game designers. The resolution of raster graphics technology was making huge advances even as the industry floundered, and advances in computer processing power were closing another gap as well. Programmers who had favored vector graphics often said that with an X/Y display’s faster draw and scan rate, it was easier to create scaleable 3-D graphics such as those seen in Battlezone and many others. The nature of drawing only point-to-point graphics made it easier to program 3-D graphics with limited processor power. But faster, better processors were quickly becoming available, capable of realistically scaling and rotating 3-D graphics on a raster monitor without sacrificing the speed of the game. The push toward photorealism was on, and vector graphics were left by the wayside, a brief detour in the evolution of the arcade – and an even briefer detour at home.

Vectrex remains a prized collectible and a completely unique evolutionary cul-de-sac, to borrow a phrase from Arthur C. Clarke, in home video gaming. Modern programmers have taken up the cause of expanding the Vectrex library with impressive results, and have even created new controllers. Thanks to these dedicated fans, the Vectrex lives on. Furthermore, Jay Smith and his former GCE colleagues released the entire Vectrex library into the public domain, ceding any copyright claims to the games they programmed at the height of the early 80s home video game gold rush; those games can now be enjoyed with startling accuracy through emulation.

But only on a raster monitor.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=275]

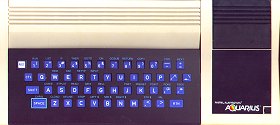

Mattel Aquarius

Was it a video game console…or a home computer?

In the sad case of Mattel’s Aquarius, the company putting it on the market simply didn’t seem to know. And of all the failed attempts of the early 1980s video game manufacturers to turn their game machines into computers, Aquarius was one of the most humbling fumbles of the entire era.

In the sad case of Mattel’s Aquarius, the company putting it on the market simply didn’t seem to know. And of all the failed attempts of the early 1980s video game manufacturers to turn their game machines into computers, Aquarius was one of the most humbling fumbles of the entire era.

The brainchild of Hong Kong-based Radofin Electronics, Aquarius seemed – at least from its outward design aesthetic – to be a study in what would happen if Mattel’s Intellivision and the My First Computer keyboard module Atari touted for the VCS had a kid. The master console itself was attractive enough, with blue rubber keys on a black-and-white casing; at a distance, the Aquarius almost looks like a slight variation on the TI 99/4A with its horizontal cartridge/expansion slot to the right of the keyboard. The “Mini-Expander Module” was needed to play games on the Aquarius, consisting of an extension to the cartridge slot and two detachable Intellivision-style controllers (though smaller, smoother and easier to hold), each with the standard “joy-disc” and a six-button keypad (as opposed to its predecessor’s twelve keys).

The brainchild of Hong Kong-based Radofin Electronics, Aquarius seemed – at least from its outward design aesthetic – to be a study in what would happen if Mattel’s Intellivision and the My First Computer keyboard module Atari touted for the VCS had a kid. The master console itself was attractive enough, with blue rubber keys on a black-and-white casing; at a distance, the Aquarius almost looks like a slight variation on the TI 99/4A with its horizontal cartridge/expansion slot to the right of the keyboard. The “Mini-Expander Module” was needed to play games on the Aquarius, consisting of an extension to the cartridge slot and two detachable Intellivision-style controllers (though smaller, smoother and easier to hold), each with the standard “joy-disc” and a six-button keypad (as opposed to its predecessor’s twelve keys).

Built into the master component itself was a bastardized version of BASIC licensed to Radofin by Microsoft (which was, at the time, still marketing such now-unthinkable products as CP/M operating systems for the Apple II). Many essential BASIC functions were missing, however; a more useful BASIC was to have been included with an ultimately unreleased expansion module for those interested in learning computer programming. (Click here for the keyboard overlay for MS Basic.)

The first (and, truly, only) wave of games released for the Aquarius were all culled from previously-released Intellivision titles. They were revamped for the new hardware, of course, but not that much was changed – if anything, the underpowered hardware of the Aquarius meant that its versions were inferior to the original Intellivision titles. That handful of titles also proved to be the last – within half a year, as the video game industry crashed and Mattel’s electronics division racked up a staggering multi-million-dollar loss, Mattel exercised a contractual option to kill the Aquarius project. The remaining inventory of hardware was sold back to Radofin Electronics (at a loss, naturally), who tried to market the Aquarius independently through 1988 before declaring it dead.

The first (and, truly, only) wave of games released for the Aquarius were all culled from previously-released Intellivision titles. They were revamped for the new hardware, of course, but not that much was changed – if anything, the underpowered hardware of the Aquarius meant that its versions were inferior to the original Intellivision titles. That handful of titles also proved to be the last – within half a year, as the video game industry crashed and Mattel’s electronics division racked up a staggering multi-million-dollar loss, Mattel exercised a contractual option to kill the Aquarius project. The remaining inventory of hardware was sold back to Radofin Electronics (at a loss, naturally), who tried to market the Aquarius independently through 1988 before declaring it dead.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=40]

Commodore 64

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the Commodore 64 still stands today as the best selling computer of all time. Its revolutionary graphic and sound chips combined with an insanely affordable price propelled the Commodore line of computers into the history books. Its 15,000+ game library didn’t hurt, either.

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the Commodore 64 still stands today as the best selling computer of all time. Its revolutionary graphic and sound chips combined with an insanely affordable price propelled the Commodore line of computers into the history books. Its 15,000+ game library didn’t hurt, either.

In the early 1980’s, three major companies competed for the exploding home computer market. While IBM marketed their computers to businessmen and Apple infiltrated the school system, the Commodore 64 shined in one very specific area: games. With a video chip (VIC) that produced an unmatched 320 x 240 resolution and 16 simultaneous colors and a sound chip (SID) capable of 3 independent voices, Commodore games quickly surpassed the games available for other computers. In fact, it was not uncommon for Apple and IBM games to feature Commodore screenshots in their marketing materials. Many people never got past the image of the Commodore 64 as a “gaming console with a disk drive.”

The Commodore 64 launched in 1982 for $595 and had dropped to $200 by 1983 (compare to the Apple IIe, which sold for $1395 in 1983). The basic system came with 64k of RAM and had BASIC and DOS built in. The Commodore 64 could be hooked to a monitor or directly to your television through an RF adapter. Games were available in three formats: cartridge, cassette tape (more prevalent in Europe), or disk drive (more prevalent in the US). One of the handiest features of the Commodore 64 was its compatibility with Atari 2600 joysticks.

The Commodore 64 wasn’t without problems. For one, Commodore systems tended to run hot. Really hot. I personally owned two fans for my system, one for the computer’s power supply and the other for my disk drive. Another big complaint early in the system’s life was the slow disk drive access times, a problem that was virtually eliminated with Epyx’s Fast Load Cartridge (and several clones that followed).

The Commodore 64 appeared in several variations over the years. In 1985, Commodore released the Commodore 128 (which could be started in either C64 or C128 mode). The Commodore 64 also appeared in a 25-pound portable version (the SX-64), and in a sleeker case which resembled the C128 and Amiga (called the Commodore 64C). Software and peripherals were completely interchangeable between these models. Later computers in the Commodore line, including the Commodore Plus 4 and the Commodore 16, would not run most Commodore 64 programs – and their sales reflected this.

In 1985, Commodore released the Amiga 1000, a spiritual successor to the Commodore 64. The Amiga contained even better graphics and sound capabilities than the Commodore 64 did, but many loyal Commodore 64 owners refused to give up their little beige boxes. 12 years after the launch of the 64, Commodore closed its doors and was eventually sold off in 1995.

While my dad had both an Apple II and an IBM XT in the living room, I had a Commodore 64 in my bedroom. I spent many nights not only playing the latest games, but talking to friends via BBSs and of course, trading games (which wasn’t nearly the big deal it is today). From Archon to Zork, I set out to play every one of those 15,000 titles. Throughout the 10 years I had my Commodore hooked up, I got through about 4,000 of them.

In an age of gigabits and gigahertz, it’s amazing that a machine that runs at 1 megahertz and holds 180k per floppy still has fans. Not only is new Commodore 64 software constantly appearing, but new pieces of hardware are appearing as well. Did you know you could connect a Commodore 1541 disk drive to your PC and transfer games back and forth? There are also devices available that allow you to connect IDE hard drives to your C64. There’s even a broadband adapter and new operating system that will allow your Commodore 64 to run TCP/IP and access the Internet! Tulip Computers, the current owners of the Commodore brand name, have even released a “30-in-1” Joystick, with 30 classic Commodore 64 games in one easy to play package. The popularity and legacy of the Commodore 64 is undeniable.

The majority of this section of Phosphor Dot Fossils focuses on what made the Commodore 64 so great and what kept it alive all those years – the games. Whether you prefer emulation or the real thing, you owe it to yourself to check out the games on this list. For nearly a decade, the Commodore 64 was the gaming system to which all other computer games were compared, many of which still hold up today.

[jwcatpostlist orderby=title order=asc includecats=122]

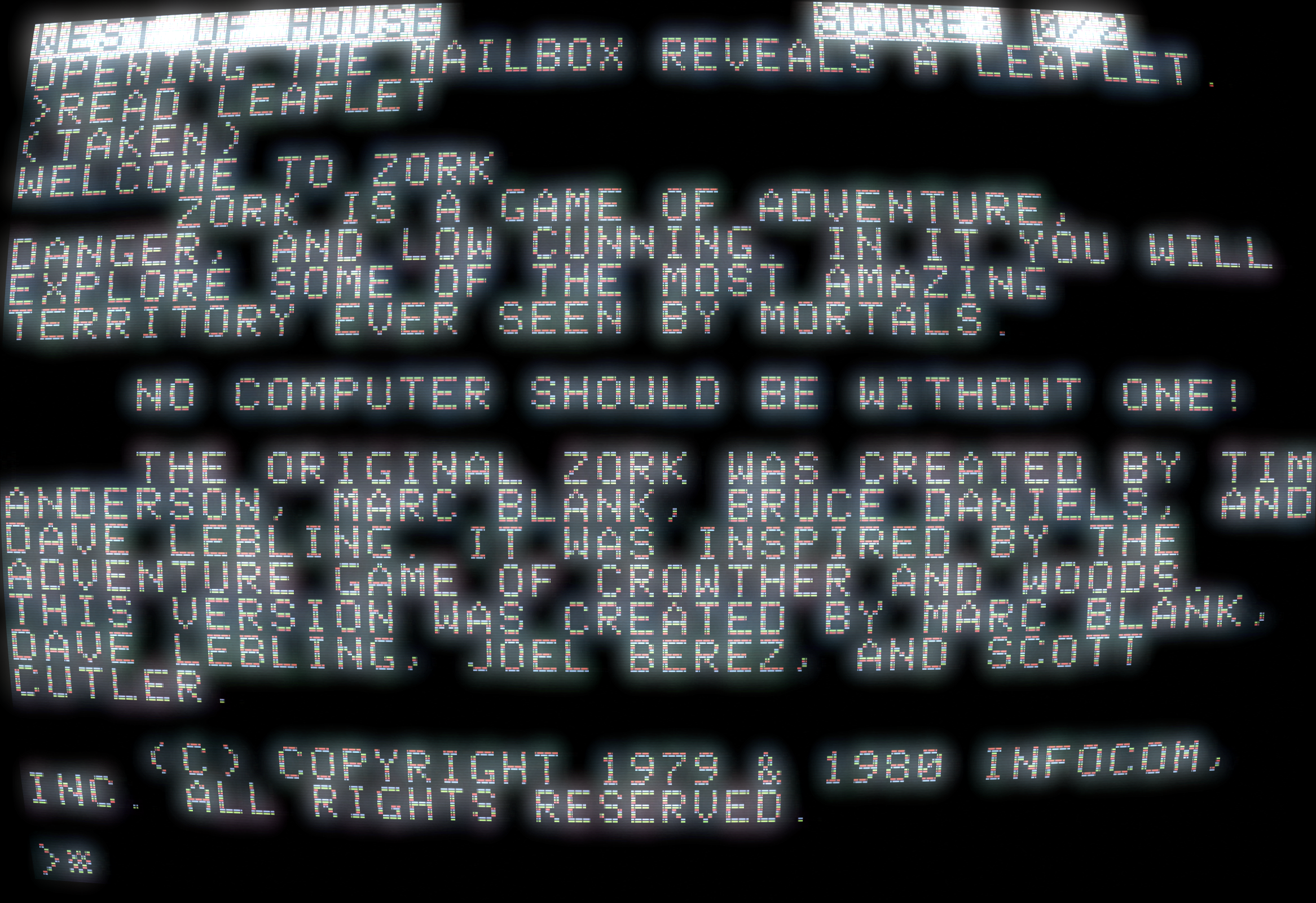

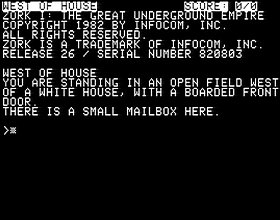

Zork I: The Great Underground Empire

The Game: You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a mailbox here. (Infocom, 1982)

The Game: You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a mailbox here. (Infocom, 1982)

Memories: A direct descendant of the Dungeons & Dragons-inspired all-text mainframe adventure games of the 1970s, only with a parser that can pick what it needs out of a sentence typed in plain English. In truth, Zork‘s command structure still utilized the Tarzan-English structure of the 70s game (i.e. “get sword,” “fight monster”), but the parser was there to filter out all of the player’s extraneous parts of speech – anything that wasn’t a noun or a verb, the game had no use for. Many a player just went the “N” (north), “U” (up), “I” (inventory) route anyway.

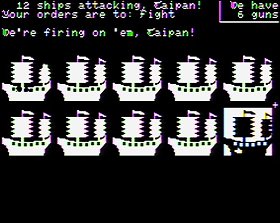

Taipan!

The Game: The coast of 19th century China could be a dangerous place – pirates lay in wait for passing (and relatively defenseless) ships, and that’s just the obvious danger. The buyer’s and seller’s markets in dry goods, weapons, silk and opium could pose just as much of a hazard to an independent trader’s finances. And then there’s Li Yuen’s protection racket… (Avalanche Productions [designed by Art Canfil], 1982)

The Game: The coast of 19th century China could be a dangerous place – pirates lay in wait for passing (and relatively defenseless) ships, and that’s just the obvious danger. The buyer’s and seller’s markets in dry goods, weapons, silk and opium could pose just as much of a hazard to an independent trader’s finances. And then there’s Li Yuen’s protection racket… (Avalanche Productions [designed by Art Canfil], 1982)

Memories: One of the first trading strategy games I ever encountered, Taipan! has been a favorite of mine for something like 20 years. When I played it as just one of many games in an all-day weekend screen grab-o-rama, I found myself playing the thing for hours.

Princess & Frog 8K

The Game: You’re a frog who has a hot date with the princess in the castle. But in order to reach her, you’ll have to cross four lanes of jousting knight traffic – avoiding the knights’ horses and lances – and then you’ll have to cross the moat on the backs of snakes and alligators, all without ending up in the drink when they submerge. (There’s also occasionally a lady frog you can hook up with en route to the castle; apparently this whole thing with the princess doesn’t have any guarantee of exclusivity.) When you reach the castle, you can hop into any open window, but if you see a pair of lips in that window, that’s where the princess is. (Romox, 1982)

The Game: You’re a frog who has a hot date with the princess in the castle. But in order to reach her, you’ll have to cross four lanes of jousting knight traffic – avoiding the knights’ horses and lances – and then you’ll have to cross the moat on the backs of snakes and alligators, all without ending up in the drink when they submerge. (There’s also occasionally a lady frog you can hook up with en route to the castle; apparently this whole thing with the princess doesn’t have any guarantee of exclusivity.) When you reach the castle, you can hop into any open window, but if you see a pair of lips in that window, that’s where the princess is. (Romox, 1982)

Memories: It probably doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that Romox’s Princess & Frog is, in fact, a cut-rate Frogger clone. And it really doesn’t even bother to change the game play at all – Princess & Frog is to Frogger what the arcade ripoff Pirhana was to Pac-Man: it tries to get by with changing the graphics and nothing else.

Turbo

The Game: It’s pretty straightforward…you’re zipping along in your Formula One race car, trying to avoid other drivers and obstacles along the way while hauling a sufficient quantity of butt to win the race. (Coleco [under license from Sega], 1982)

The Game: It’s pretty straightforward…you’re zipping along in your Formula One race car, trying to avoid other drivers and obstacles along the way while hauling a sufficient quantity of butt to win the race. (Coleco [under license from Sega], 1982)

Memories: One of the seminal first-person racing games of the 80s, Turbo was one of several Sega coin-ops that caught the eye of Coleco. The one hurdle in bringing it to the ColecoVision? Having to invent a whole new controller that would be similar enough to Turbo‘s arcade control scheme without being so specific as to rule out using the driving controller for other games in the future. And thus was born Expansion Module #2, a steering wheel controller with a detachable “gas pedal.”

Type & Tell

The Game: You type! It talks! And occasionally you have to throw the damnedest misspellings at it to get it to say the simplest words. And despite the back of the box claiming that it “plays fun games,” it’s much more likely that it’ll just make some fun (and weird) sounds. (Magnavox, 1982)

The Game: You type! It talks! And occasionally you have to throw the damnedest misspellings at it to get it to say the simplest words. And despite the back of the box claiming that it “plays fun games,” it’s much more likely that it’ll just make some fun (and weird) sounds. (Magnavox, 1982)

Memories: A pack-in cartridge included with the Voice of Odyssey 2, Type & Tell is actually a barely-glorified Odyssey version of Speak ‘n’ Spell, except everything it says is in a monotone robotic voice which one of the video game magazines of the time once described as “Darth Vader on quaaludes.” (One of these days, remind me to tell you about my mother’s reaction when I asked her, after reading that review, what quaaludes were.)

The Game: The future! A dystopia of fast driving! Players are behind the wheel of a multi-terrain vehicle that can switch from fast handling on solid surfaces to amphibious speedboat in the blink of an eye. The currency of this violent future is fuel for this vehicle, and enemies in similar vehicles and in airborne vehicles will stop at nothing to claim fuel for themselves, regardless of the player’s safety. Grey highways and rivers are the usual modes of travel, though brown highways offer faster travel. Checkpoints must be reached in the correct order to rack up bonus points (players who arrive at the wrong checkpoint will be greeted with a checkerboard pattern instead of a number), but all checkpoints, even the wrong ones, grant players extra fuel. Surface enemies can be rammed out of the way, but there’s no honor lost in surviving by throwing the vehicle into reverse gear. Whoever survives the longest and scores the highest is crowned the Supreme King of the World. (Taito America, 1982)

The Game: The future! A dystopia of fast driving! Players are behind the wheel of a multi-terrain vehicle that can switch from fast handling on solid surfaces to amphibious speedboat in the blink of an eye. The currency of this violent future is fuel for this vehicle, and enemies in similar vehicles and in airborne vehicles will stop at nothing to claim fuel for themselves, regardless of the player’s safety. Grey highways and rivers are the usual modes of travel, though brown highways offer faster travel. Checkpoints must be reached in the correct order to rack up bonus points (players who arrive at the wrong checkpoint will be greeted with a checkerboard pattern instead of a number), but all checkpoints, even the wrong ones, grant players extra fuel. Surface enemies can be rammed out of the way, but there’s no honor lost in surviving by throwing the vehicle into reverse gear. Whoever survives the longest and scores the highest is crowned the Supreme King of the World. (Taito America, 1982) The Game: You are a frog. Your task is simple: hop across a busy highway, dodging cars and trucks, until you get the to the edge of a river, where you must keep yourself from drowning by crossing safely to your grotto at the top of the screen by leaping across the backs of turtles and logs. But watch out for snakes and alligators! (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: You are a frog. Your task is simple: hop across a busy highway, dodging cars and trucks, until you get the to the edge of a river, where you must keep yourself from drowning by crossing safely to your grotto at the top of the screen by leaping across the backs of turtles and logs. But watch out for snakes and alligators! (Coleco, 1982) The Game: An oversized gorilla kidnaps Mario’s girlfriend and hauls her up to the top of a building which is presumably under construction. You are Mario, dodging Donkey Kong’s never-ending hail of rolling barrels and “foxfires” in your attempt to climb to the top of the building and topple Donkey Kong. You can actually do this a number of times, and then the game begins again with the aforementioned girlfriend in captivity once more. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: An oversized gorilla kidnaps Mario’s girlfriend and hauls her up to the top of a building which is presumably under construction. You are Mario, dodging Donkey Kong’s never-ending hail of rolling barrels and “foxfires” in your attempt to climb to the top of the building and topple Donkey Kong. You can actually do this a number of times, and then the game begins again with the aforementioned girlfriend in captivity once more. (Coleco, 1982) The Game: Not happy with her consort’s defeat at your hands (assuming, of course, that you won Ultima I, the enchantress Minax tracks you down to your home planet of Earth and begins the test anew, sending legions of daemons and other hellspawn to strike you down before you can gain enough power to challenge her. This time, you have intercontinental and even interplanetary travel at your disposal via the moongates, which appear and disappear based on the phases of the moon. Each destination has unique challenges that help to prepare you for the showdown with Minax herself. (Sierra On-Line, 1982)

The Game: Not happy with her consort’s defeat at your hands (assuming, of course, that you won Ultima I, the enchantress Minax tracks you down to your home planet of Earth and begins the test anew, sending legions of daemons and other hellspawn to strike you down before you can gain enough power to challenge her. This time, you have intercontinental and even interplanetary travel at your disposal via the moongates, which appear and disappear based on the phases of the moon. Each destination has unique challenges that help to prepare you for the showdown with Minax herself. (Sierra On-Line, 1982) The Game: A party of up to four adventurers descends into the depths of a dungeon to recover their kidnapped king and find his magical orb. Along the way, the band of intrepid adventurers will have to fight off everything from packs of wild dogs to evil creatures determined to bring the quest to an early end. (Texas Instruments, 1982)

The Game: A party of up to four adventurers descends into the depths of a dungeon to recover their kidnapped king and find his magical orb. Along the way, the band of intrepid adventurers will have to fight off everything from packs of wild dogs to evil creatures determined to bring the quest to an early end. (Texas Instruments, 1982) The Game: Up to two players control light cycles that leave a solid light trail in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other player by surrounding them with a light trail that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to run into their own trail. Coming into contact with a light trail, either yours or the other player’s, collapses your own trail and ends your turn. The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (“Ivan”, circa 1982)

The Game: Up to two players control light cycles that leave a solid light trail in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other player by surrounding them with a light trail that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to run into their own trail. Coming into contact with a light trail, either yours or the other player’s, collapses your own trail and ends your turn. The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (“Ivan”, circa 1982) The Game: Using primitive text-based graphics, Telengard books for you a no-expenses-paid vacation through dungeons and hallways full of orcs and other nasties. If you can map the twisty passages, you might just make it back to the Adventurers’ Inn to claim your newfound experience points and heal from your many battles…and if you get lost? There are other inns out there – and many painful ends as well. (Avalon Hill, 1982)

The Game: Using primitive text-based graphics, Telengard books for you a no-expenses-paid vacation through dungeons and hallways full of orcs and other nasties. If you can map the twisty passages, you might just make it back to the Adventurers’ Inn to claim your newfound experience points and heal from your many battles…and if you get lost? There are other inns out there – and many painful ends as well. (Avalon Hill, 1982) The Game: Hellish flying demons try to formation-dive your well-armed, devil-fryin’ vehicle at the bottom of the screen. Each time you knock one of this gargoylesque beasties out of the sky, they drop a piece of a bridge you must drag over to the appropriate spot on the screen. When you’re close to completing the bridge, the Prince of Darkness sends in some heavier artillery – a spooky floating demon head who spits fire at your cannon – to do away with you. Once you’ve toasted the flying meanies out of the sky and cross the bridge, it’s time to do battle with Satan himself. (CBS Video Games, 1982)

The Game: Hellish flying demons try to formation-dive your well-armed, devil-fryin’ vehicle at the bottom of the screen. Each time you knock one of this gargoylesque beasties out of the sky, they drop a piece of a bridge you must drag over to the appropriate spot on the screen. When you’re close to completing the bridge, the Prince of Darkness sends in some heavier artillery – a spooky floating demon head who spits fire at your cannon – to do away with you. Once you’ve toasted the flying meanies out of the sky and cross the bridge, it’s time to do battle with Satan himself. (CBS Video Games, 1982) The Game: Rocky is trying to build machines to kick stuff. He provides players with a number of connectors and components, and shows them how they can be used to achieve different tasks. (The Learning Company, 1982)

The Game: Rocky is trying to build machines to kick stuff. He provides players with a number of connectors and components, and shows them how they can be used to achieve different tasks. (The Learning Company, 1982) The Game: You control a space patrol fighter cruising over the surface of a planet. Alien attackers swarm on the right side of the screen and strafe you, and you must get out of the way of their laser fire and return some of your own; the more enemy ships you allow to safely leave the screen, the more you’ll have to deal with when they re-enter from the right side of the screen. Avoid their fire, avoid colliding with them, and avoid slamming into the ground, and you might just live long enough to repel the invasion. (Texas Instruments, 1982)

The Game: You control a space patrol fighter cruising over the surface of a planet. Alien attackers swarm on the right side of the screen and strafe you, and you must get out of the way of their laser fire and return some of your own; the more enemy ships you allow to safely leave the screen, the more you’ll have to deal with when they re-enter from the right side of the screen. Avoid their fire, avoid colliding with them, and avoid slamming into the ground, and you might just live long enough to repel the invasion. (Texas Instruments, 1982) The Game: You control a round creature consisting of a mouth and little else. When the game begins, you’re given about two seconds’ head start to venture into the maze before blobby monsters are released from their cages and begin pursuing you. As you move, Munch Man leaves a trail in his wake; you advance to the next level of the game by “painting” the entire maze with that trail. (Texas Instruments, 1982)

The Game: You control a round creature consisting of a mouth and little else. When the game begins, you’re given about two seconds’ head start to venture into the maze before blobby monsters are released from their cages and begin pursuing you. As you move, Munch Man leaves a trail in his wake; you advance to the next level of the game by “painting” the entire maze with that trail. (Texas Instruments, 1982) The Game: Ever had a sweet tooth? Now you are the sweet tooth – or teeth, as the case may be. You guide a set of clattering teeth around a mazelike screen of horizontal rows; an opening in each row travels down the wall separating it from the next row. Your job is to eat the tasty treats lining each row until you’ve cleared the screen. Naturally, it’s not just going to be that easy. There are nasty hard candies out to stop you, and they’ll silence those teeth of yours if they catch you – and that just bites. Periodically, a treat appears in the middle of the screen allowing you to turn the tables on them for a brief interval. Sierra On-Line, 1982

The Game: Ever had a sweet tooth? Now you are the sweet tooth – or teeth, as the case may be. You guide a set of clattering teeth around a mazelike screen of horizontal rows; an opening in each row travels down the wall separating it from the next row. Your job is to eat the tasty treats lining each row until you’ve cleared the screen. Naturally, it’s not just going to be that easy. There are nasty hard candies out to stop you, and they’ll silence those teeth of yours if they catch you – and that just bites. Periodically, a treat appears in the middle of the screen allowing you to turn the tables on them for a brief interval. Sierra On-Line, 1982 The Game: Players control a single laser cannon responsible for defending several planets who don’t seem to be able to look out for themselves. The cannon squares off against an alien mothership which deploys its own fleet of attack ships to destroy those planets. Good news: the planets are protected by a force field spanning the bottom of the screen. Bad news? The aliens can shoot through it, exposing the row of fragile planets as they scroll across the screen like shooting gallery targets. Worse news? You can’t defend all of them forever. (Games By Apollo, 1982)

The Game: Players control a single laser cannon responsible for defending several planets who don’t seem to be able to look out for themselves. The cannon squares off against an alien mothership which deploys its own fleet of attack ships to destroy those planets. Good news: the planets are protected by a force field spanning the bottom of the screen. Bad news? The aliens can shoot through it, exposing the row of fragile planets as they scroll across the screen like shooting gallery targets. Worse news? You can’t defend all of them forever. (Games By Apollo, 1982) The Game: The constant struggle between cat and dog requires a great deal of concentration. Two players can play, or one player can control the dog while the CPU makes moves as the “Microcat.” Each animal drops a piece into the playing field, trying to line up four pieces horizontally, vertically or diagonally, or trying to keep the other animal from lining up his four pieces. Whoever lines up four pieces first wins the game. (Phillips, 1982)

The Game: The constant struggle between cat and dog requires a great deal of concentration. Two players can play, or one player can control the dog while the CPU makes moves as the “Microcat.” Each animal drops a piece into the playing field, trying to line up four pieces horizontally, vertically or diagonally, or trying to keep the other animal from lining up his four pieces. Whoever lines up four pieces first wins the game. (Phillips, 1982) The Game: You’re the sole space fighter pilot penetrating a heavily-armed, mobile alien fortress. If you can survive wave after wave of fighters and ground defenses, you’ll have the opportunity to destroy the Zaxxon robot at the heart of the complex. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: You’re the sole space fighter pilot penetrating a heavily-armed, mobile alien fortress. If you can survive wave after wave of fighters and ground defenses, you’ll have the opportunity to destroy the Zaxxon robot at the heart of the complex. (Coleco, 1982) The Game: You’re the pilot of a lone fighter ship, screaming down the trench-like, heavily armed confines of a spaceborne fortress, on a mission to find and destroy the Zaxxon robot – the most heavily guarded of all – at the heart of the structure. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: You’re the pilot of a lone fighter ship, screaming down the trench-like, heavily armed confines of a spaceborne fortress, on a mission to find and destroy the Zaxxon robot – the most heavily guarded of all – at the heart of the structure. (Coleco, 1982) The Game: Trapped in a maze full of HallMonsters, you are adventurer Winky, on a mission to snatch incredible treasures from hazardous underground rooms inhabited by lesser beasts such as re-animated skeletons, goblins, serpents, and so on. Sometimes even the walls move, threatening to squish Winky or trap him, helpless to run from the HallMonsters. The deeper into the dungeons you go, the more treacherous the danger – and the greater the rewards. Just remember two things – the decomposing corpses of the smaller enemies are just as deadly as the live creatures. And there is no defense – and almost never any means of escape – from the HallMonsters. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: Trapped in a maze full of HallMonsters, you are adventurer Winky, on a mission to snatch incredible treasures from hazardous underground rooms inhabited by lesser beasts such as re-animated skeletons, goblins, serpents, and so on. Sometimes even the walls move, threatening to squish Winky or trap him, helpless to run from the HallMonsters. The deeper into the dungeons you go, the more treacherous the danger – and the greater the rewards. Just remember two things – the decomposing corpses of the smaller enemies are just as deadly as the live creatures. And there is no defense – and almost never any means of escape – from the HallMonsters. (Coleco, 1982) The Game: As intrepid (and perpetually happy) adventurer Winky, armed only with a bow and arrow, you’re on a treasure hunt of the deadliest kind. HallMonsters try to stop you at every turn, and their minions guard the individual treasures that lie in the rooms of the maze. You can kill the smaller creatures (though their decomposing remains are still deadly to touch), but the HallMonsters are impervious to your arrows – and you’re lunch. (Coleco, 1982)

The Game: As intrepid (and perpetually happy) adventurer Winky, armed only with a bow and arrow, you’re on a treasure hunt of the deadliest kind. HallMonsters try to stop you at every turn, and their minions guard the individual treasures that lie in the rooms of the maze. You can kill the smaller creatures (though their decomposing remains are still deadly to touch), but the HallMonsters are impervious to your arrows – and you’re lunch. (Coleco, 1982) The Game: Your Vanguard space fighter has infiltrated a heavily-defended alien base. The enemy outnumbers you by six or seven to one at any given time (thank goodness for animated sprite limitations, or you’d be in real trouble!). You can fire above, below, ahead and behind your ship, which is an art you’ll need to master since enemy ships attack from all of these directions. You can’t run into any of the walls and expect to survive, but you can gain brief invincibility by flying through an Energy block, which supercharges your hull enough to ram your enemies (something which, at any other time, would mean certain death for you as well). At the end of your treacherous journey lies the alien in charge of the entire complex – but if you lose a life at that stage, you don’t get to come back for another shot! (Atari, 1982)

The Game: Your Vanguard space fighter has infiltrated a heavily-defended alien base. The enemy outnumbers you by six or seven to one at any given time (thank goodness for animated sprite limitations, or you’d be in real trouble!). You can fire above, below, ahead and behind your ship, which is an art you’ll need to master since enemy ships attack from all of these directions. You can’t run into any of the walls and expect to survive, but you can gain brief invincibility by flying through an Energy block, which supercharges your hull enough to ram your enemies (something which, at any other time, would mean certain death for you as well). At the end of your treacherous journey lies the alien in charge of the entire complex – but if you lose a life at that stage, you don’t get to come back for another shot! (Atari, 1982)

The Game: Players pilot a ship trapped in a maze of vertically stacked level, teeming with aliens who are all deadly to the touch. The good news is that the ship has an inexhaustible supply of ammo. The not-so-good news is that the bad guys have an inexhaustible supply of bad guys. Players have to keep the ship from colliding with the enemy, while shooting at the enemy and watching out for split-second opportunities to grab any bonus items that may make a fleeting appearance. Just one word of caution: the prizes turn into smart bombs if you wait too long to go pick them up. (20th Century Fox, 1982)

The Game: Players pilot a ship trapped in a maze of vertically stacked level, teeming with aliens who are all deadly to the touch. The good news is that the ship has an inexhaustible supply of ammo. The not-so-good news is that the bad guys have an inexhaustible supply of bad guys. Players have to keep the ship from colliding with the enemy, while shooting at the enemy and watching out for split-second opportunities to grab any bonus items that may make a fleeting appearance. Just one word of caution: the prizes turn into smart bombs if you wait too long to go pick them up. (20th Century Fox, 1982)