Spaceflight is routine and completely safe.

Spaceflight is routine and completely safe.

Or so that was the thinking in 1985, when space shuttle Challenger took off for her eighth flight that July and experienced the most serious post-launch, pre-orbit emergency that any of the shuttle orbiters would encounter for… well… the next six months.

Here’s the video of the launch; go ahead and start playing it and listen along as you read.

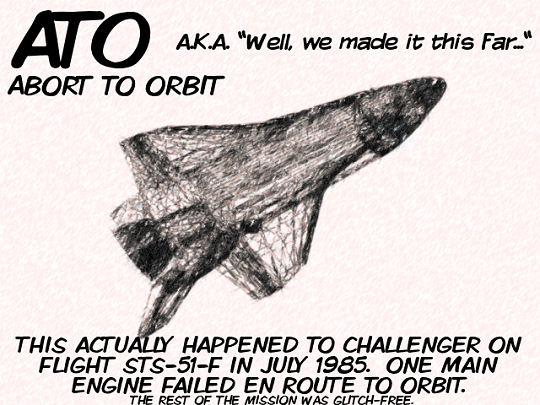

Challenger’s center main engine – the one directly beneath her rudder – shut down prematurely. The shuttle was close enough to orbit that the crew was orderd to execute an “ATO”: Abort To Orbit by gunning the remaining engines (this happened after the solid rocket boosters were jettisoned). With sufficient altitude, there’s less atmospheric drag, and enough fuel from the main tank has been consumed that the remaining stack (the shuttle and the external tank) is lighter. Two engines will get it into at least a low orbit.

In an Abort To Orbit situation, once the shuttle is safely in orbit, ground controllers can assess the situation and make a decision about whether the shuttle can carry out its mission objectives in that lower orbit, or if it needs to return at the earliest opportunity.

But Challenger wasn’t out of the woods yet. If you listen close, there’s a lot of chatter a couple of minutes later about setting “limits to inhibit” – the shuttle’s computer was within seconds of shutting down a second main engine because of the added heat tripping a sensor (remember, the two remaining engines are working harder at this point). Another engine shutting down would have left Challenger with only one main engine, insufficient to keep the shuttle aloft. The result would’ve been the whole stack tumbling back to Earth at mach 4, with countless screaming astronauts. By switching the engine limits to “inhibit,” the pilot told the computer: ignore those sensors and keep firing the engine until I manually shut it down.

The call from ground control to inhibit the automatic shutdown likely prevented what could have been the first all-hands-lost American space disaster. At this point, someone probably should have hung some fuzzy dice in Challenger’s cockpit; it couldn’t have hurt.

Not that I’m suggesting a jinx… oh, now you can just cut that crap out right now.

If you’re anything like me – and I’m a rabid space nut – you don’t remember any mention of an emergency back in the day; it all sounds so casual that it’s unlikely anyone else does either, especially since the rest of the flight went without a hitch and the shuttle flights were firmly into “unremarkable” territory just four years into the shuttle program. Today, of course, it would have been all over the news (but probably only in the B block); after another successful flight in November 1985, Challenger would – not in a way that anyone would have chosen – cause a sea change in thinking on transparency within NASA. But for now, even the mission’s successes – carrying the second international Spacelab module and its mission specialists into orbit for eight days – went mostly unnoticed.

There were other abort modes that were used during the shuttle program – and others that thankfully weren’t used – as well.

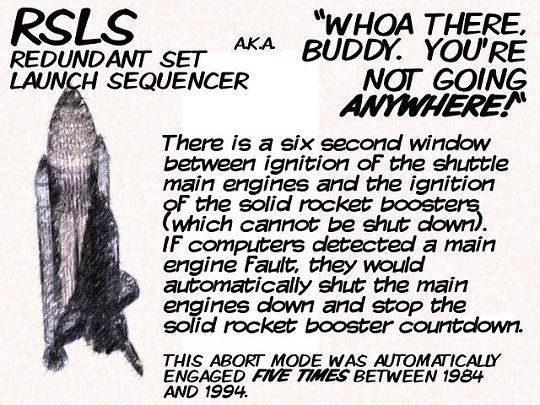

The most common abort mode was RSLS, which kept the shuttle on the ground. Automatic systems constantly polled all of the shuttle’s hardware for temperature, pressure, and other readings, and any anomaly detected would cause a hold in the countdown. But between T-6 seconds and T-0 seconds, RSLS could still ground the shuttle by interrupting the launch sequence before the solid rocket boosters fired. Unstoppable once ignited, the solid rocket boosters meant the vehicle had to leave the ground and jettison the SRBs before anything else could be done. RSLS would stop them from firing at all and keep the vehicle on the ground (the three main engines alone would not lift the stack).

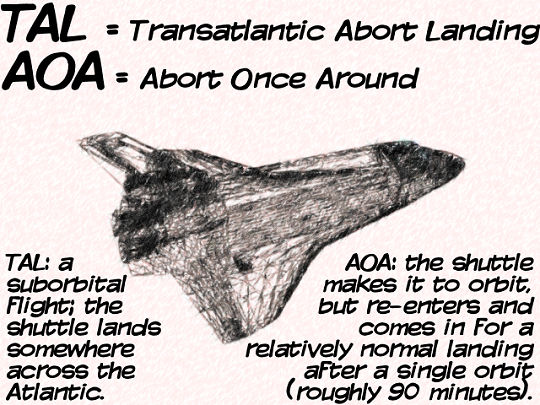

The Transatlantic Abort Landing was reserved for situations where an Abort To Orbit was impossible, but the vehicle was still flight-worthy for a short period of time. It presumed that the shuttle would remain on course, firing its engines until it achieved enough speed to cross the Atlantic, at which point it would ditch the fuel tank and glide to a landing at one of several carefully selected airstrips (which had to meet certain requirements for length, surface, etc.) in friendly territory, with prior arrangements having been made with the local governments by NASA and the State Department. This abort would probably have been extremely stressful on the shuttle itself, but was within the realm of survivability. It will probably surprise absolutely no one to discover that the ever-shifting geopolitical situation meant that the list of friendly landing sites for a TAL abort in 1981 was significantly different from the list of candidate airstrips in 2011.

Abort Once Around was somewhat similar to Abort To Orbit: it got the shuttle into space, but presumed a serious enough emergency that the vehicle would deorbit and land after a single, 90-minute orbit. Neither of these abort modes ever had to be put into practice.

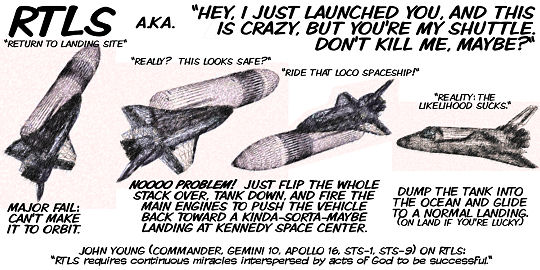

Nor did Return To Landing Site, thankfully.

The craziest shuttle abort profile, RTLS (return to landing site), involved flipping the shuttle over with the external tank still tied to its belly before leaving the atmosphere, firing the engines to kill both its climb and forward momentum and hopefully boost it back toward the east coast of the United States where it could return to the KSC runway… in theory. (Presumably this theory also assumed that there was little fuel left in the tank, that the shuttle/tank combo had aerodynamic potential in this orientation, and that there would be no frictional heating to compromise the outer skin of the tank and ignite the remaining fuel inside with the shuttle still attached. If we’re making all those assumptions, this abort profile might as well also assume that a flight of angels will carry the shuttle home safely on a cloud of fairy dust, hopes and dreams, and rainbow-scented unicorn farts.)

Declassified test footage of RTLS landing system

At one point, the first 1981 launch of Columbia was going to be a sub-orbital flight to test this abort mode, until mission commander (and former Gemini/Apollo astronaut) John Young flatly refused to fly that mission profile. Three-time mission specialist Mike Mullane, in his autobiography “Riding Rockets”, called the RTLS abort mode an “unnatural act of physics” – he firmly believed it would have failed catastrophically if put into practice.

Just in case Mullane was right on the money, R&D came up with… this.

A study was put forth to add a fifth solid fuel segment to the solid rocket boosters, giving the entire stack enough oomph that the only abort mode required would be ATO; the extra segment of fuel would have kept the SRBs attached to the stack for a longer period of time, lifting it further and reducing the amount of time that the shuttle’s main engines were the only thing boosting the vehicle into orbit.

Obviously, after the events of the following January, the idea of having the SRBs strapped to the vehicle for any longer than necessary was deemed A Really Bad Idea. The five-segment SRB was never used. Every shuttle crew continued to fly RTLS aborts in simultators, so NASA clearly believed it was a survivable option.

But it seems that the plan to revert to using a capsule command module/service module stack, rather than a derivative of the shuttle itself, has eliminated the need for the kind of nearly-impossible Hail Mary pass that RTLS represented. The Orion vehicle currently under development would use the “launch abort tower” system that was in place during the Mercury and Apollo programs: a truss-like tower atop the crew capsule whose built-in rockets could pull that capsule free in the event of a catastrophic launch emergency (such as the booster never making it to orbit, or exploding en route).

Spaceflight is not routine, nor is it completely safe. And it never was. This article and the associated images aren’t meant to be disrespectful to NASA. There were 133 flights – STS-51-F included – where the shuttle took off, enabling the crew to do what they went to space to do, and returned safely. Before the shuttle, there were nine missions that went to the moon, six of which landed, and one of which went all kinds of wrong, and the crew still returned alive. Since the shuttle… well, there’s a new robot taking up residence on Mars whose very presence says that NASA’s better at these Hail Mary passes than most government agencies.

I hope they never stop.

(Click on any of the mission abort profiles to see a bigger version. Renders done by me in 3DSmax and magically pencil-ized in Paint Shop Pro.)

+ There are no comments

Add yours