He was the program director of a radio station that, since it was a satellite radio affiliate, didn’t really require programming as such. He had a George-Jones-in-the-’70s haircut and an old-school radio voice.

He was the program director of a radio station that, since it was a satellite radio affiliate, didn’t really require programming as such. He had a George-Jones-in-the-’70s haircut and an old-school radio voice.

I had a demo tape I’d recorded at home. I was puffed up because I’d received quite a few compliments on my speaking voice at various high school speech competitions. And I’d seen Good Morning Vietnam about ten times. I had this radio thing down. I also showed up for the interview, demo tape in hand, with hair down to the small of my back (in a ponytail no less), wearing flip flips and my usual uniform of madly clashing day-glo shorts and a tank top. I was really serious about this radio gig. In short, I’m not sure there was a way in which I wasn’t a punk at the time.

I should also mention that I was 17, in between my junior and senior years of high school, and that he was an old hand at the radio business, going all the way back to when radio started to be a business that one could be in. To his great credit, George didn’t laugh me out of the room. With the get-up I showed up in for a job interview, he easily could have; most would have. Instead, he pointed me toward the punishing hours of the shift he was hiring for – Saturday and Sunday morning sign-on on the FM station, which meant I had to be up at 4 to be at the station at 4:30 to shut off the security alarm and fire up the (then very analog) transmitter. He didn’t care what I was wearing or would be wearing; he wanted to know when I could start.

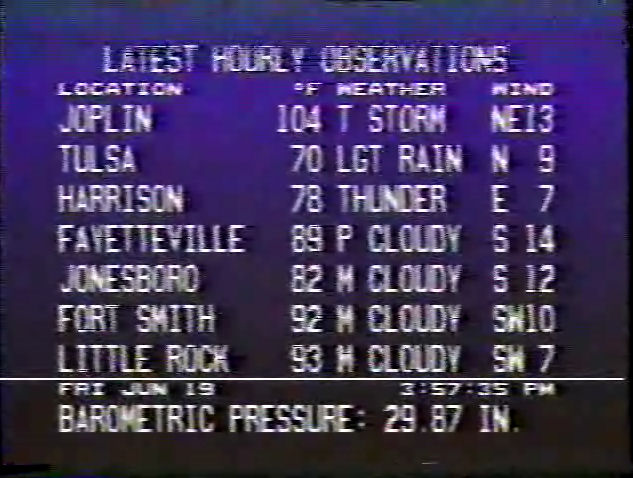

And suddenly, I’d gone from people telling me I should work in radio to actually working in radio. The hours really were painful for a night-owl like me: 4 in the morning? That’s when I usually finally gave up and went to bed, let alone rolling out of bed at that time. And it wasn’t glamorous. And twenty more viewings of Good Morning Vietnam wouldn’t have helped me. The first time one of the regular DJs put an open microphone in front of me, I didn’t blindside the world with radio brilliance that put Robin Williams to shame. I sat there without my mouth opening soundlessly, like a fish gasping for air after being yanked unceremoniously out of water. All that was actually required of me was to blurt out 23 seconds’ worth of the local weather forecast over a trippy music bed that would make even the most sober listeners start hunting for a little bag of Doritos, and here I was, Mr. Gonna Set The Radio World On Fire, not even managing to do that.

Frankly, how I kept the job after the first couple of nights is unknown even to me to this day.

When my senior year of high school started and I had a rough idea of how many Saturday mornings I’d need off for that year’s speech competitions – which were part of your grade in speech/drama and were not an elective – I took a deep breath and presented the management at the radio station with the list of days I’d need off. Considering that I worked only Saturdays and Sundays, this was actually asking a lot. Out of the “big three” folks managing the station, George was the only one who put his foot down and said that I’d be able to keep my job even when I was missing one of my two days a week for several weeks out of that spring. You’d think that would fail the “best two out of three” test by any other measure, but George put his foot down hard enough to leave a mark. I still had a job.

Ironically, one of the categories I was competing in on those “Saturdays off” (which usually meant round trip bus rides plus an all-day stay that added up to a longer day than a shift at the radio station) was… broadcast speaking. I doubted there was a rule against competitors being actively employed in broadcasting because, quite frankly, at my age, it was a conflict of interests that was extremely unlikely to arise. I seldom lost or even placed second in that category.

At the end of 1991, I finally left the first radio station where I worked, having landed a job at a station that, quite frankly, did more local stuff and was interested in having me work on the production end, writing and voicing commercials, which is where I saw more of a future. It was still a satellite station – in fact, it was an affiliate of a different “format” operated by the same company, which was helpful since I was already familiar with how it all worked – but I was able to shift toward production, which is the track I followed into TV a year and a half later, for a career of both fun and frustration.

None of which might have happened if not for George Glover taking a chance on the long-haired kid in the tank top.

George died a year ago April 19th, a few months ahead of the expiration date on that aforementioned career of mine, which seems strangely appropriate. I got out of the game with a family and a sliver of my sanity intact, and I’m even working on getting back to where I sleep at night like the rest of the human race (it’s a long, slow journey back to being awake during the day when you’ve been professional night owl for so long). I think I got out while it was still possible to leave with a bit of sanity in your pocket, and looking back at the good stuff about that line of work, George is one of those folks I think about who gave me a chance – one, perhaps, that I wasn’t necessarily dressed well enough to earn when I went in for the interview.

If only there were more like him. Thanks, George.

+ There are no comments

Add yours