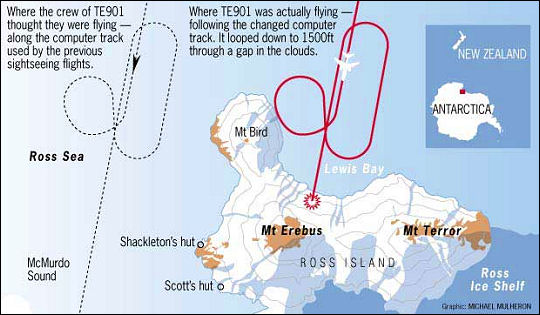

Previously on Scribblings… this week I’ve been writing about Air New Zealand flight TE901, an Antarctic passenger sightseeing flight that crashed into Mt. Erebus on November 28, 1979, killing all aboard. Yesterday, I looked at the institutional mistakes that were made leading up to the tragic accident. Today, the accident itself.

In the cockpit of flight 901 were Captain Jim Collins, co-pilot Greg Cassin, flight engineers Gordon Brooks and Nick Moloney, and tour guide Peter Mulgrew, a close friend and fellow adventurer of Sir Edmund Hillary himself; Hillary and Mulgrew alternated tour guide duties on the Antarctic flights, and Mulgrew was in fact filling in for Hillary, who had a prior commitment on the day of the flight.

Dense clouds greeted flight 901 once the plane was in radio range of McMurdo Base; the base’s “air traffic control,” nicknamed Ice Tower, had picked up the plane’s transponder and gave them descent clearance for lower-altitude operations. But what neither party knew was the exact position of the other: McMurdo was not directly ahead of flight 901, but to the plane’s right (from the perspective of the cockpit). Flight 901 was not coming in to McMurdo’s west, but well to its east, directly toward Mt. Erebus, due to the navigational change programmed into the plane’s computer with no notification to the flight crew:

The banking maneuver intended to loop the plane around and down to its “tourist” altitude brought flight 901 under the cloud bank at last, but this created a new and deadly problem. With the sun behind the plane, the clouds overhead, and fog and snow/ice below, the view through the cockpit windows was reduced to a flat, high-albedo glare offering no clues of what was ahead. Distance could not be judged. Flight 901 was flying through clear air, but it was absolutely impossible to see that it was roaring toward the base of a mountain at about 500mph.

Worse, the flight crew and Mulgrew fully expected that the plane’s autopilot had brought them to McMurdo Sound, a low, flat ice plain with no high terrain to avoid. Trying to pick out distinguishing landmarks in a total visual whiteout – not a meteorological or precipitiation-incuded whiteout – Collins and his crew “saw” what they expected to see, not having been briefed on an approach to Mt. Erebus. The terrain that they didn’t realize was there began interfering with communications. Even at 1500 feet, if they’d been flying over McMurdo Sound as anticipated, autopilot would’ve kept the plane safe.

A perfect storm of bad, piled on top of plenty of bad that was already looming ahead.

- Brooks: …having a bit of trouble with radio contact at the moment.

- Moloney: Have you got the squelch off?

- Brooks: …clearance to go down.

- Cassin: Say again.

- Moloney: Have you got the squelch off on that?

- Cassin: Yes, on both.

- Moloney: Try putting number two on that frequency.

- Cassin: Ah shit.

- Brooks: Lost contact when we got down a bit lower.

- Collins: Um… wonder if they can get us on 1-2-1-5 then?

- Cassin: Right, shall I try it on 1-2-1-5?

- Collins: Well look, go back to HF [high frequency comms].

- Cassin: Yep.

- Collins: Tell him we can make a visual… descent, descending to the, ah…

- Brooks: My God.

- Collins: …on a grid of 1-8-0.

- Cassin: Yep.

- Collins: …and, ah, make a visual approach to McMurdo.

- Cassin: OK.

- Cassin: Ah, Mac Center, New Zealand.

- Ice Tower: Zero one, Mac Center, go ahead.

- Cassin: Roger, 9-0-1 still negative contact on VHF. We are VMC [visual meteorological conditions – sky is clear enough to fly by sight] and, ah, we’d like to let down on a grid of 1-8-0 and proceed visually to McMurdo.

- Ice Tower: New Zealander niner-zero-one, maintain VMC and keep us advised of your altitude as you approach McMurdo, over.

- Cassin: Ah, roger, 9-0-1 we will maintain VMC.

- Collins: Well, we’re gonna go in VMC and then come back in.

- Cassin: Turn at two thousand.

- Ice Tower: New Zealand niner-zero-one, Mac Center report ten DME [distance measurement using VHF signal propagation delay almost as a sonar measurement] from McMurdo.

- Cassin: Ah, roger, 9-0-1 to report ten DME, McMurdo.

Two thousand feet is armed.

- Collins: Right.

Hold. Hold. We’ve VMC around this way.

- Brooks: You can get in here now.

- Mulgrew: Can I get out a mike there?

- Moloney: Yeah, you can get a mike there.

- Collins: Sorry, I haven’t got time to talk, but uh…

- Mulgrew: Ah, we can’t talk if you can’t see.

- Collins: The… ah… both the VHF channels that they use here… we’re not picking them up at fifty miles.

- Brooks: Do you want to swap around while he’s…

- Moloney: Commentating? Yep.

- Mulgrew: There you go, there’s some land ahead.

- Collins: I’ll arm the nav again.

- Cassin: OK.

- Collins: Alt nav cap IAS hold.

- Cassin: I’ll go back to 1-2-6-2, eh Jim?

- Collins: OK. Keeps you busy on comm, doesn’t it?

- Cassin: Well you know, ah, it’s a bit of a nuisance.

- Brooks: Are we up to here now? [sound of rustling paper]

- Ice Tower: New Zealand niner-zero-one, Mac Center. If possible give us a tops report on the, ah, cloud layers.

- Collins: Ah, OK. At, ah, 50 miles north it was ten thousand.

- Cassin: OK. Ah, roger New Zealand 9-0-1, fifty miles north the base was one zero thousand, ten thousand.

- Ice Tower: Understand, base is at ten thousand.

- Cassin: Affirmative, we are now at 6000, ah, descending to 2000 and, ah, we are VMC.

- Ice Tower: 9-0-1 roger.

- Brooks: Ah, you’re… five thousand feet. We’re going down to two.

- Collins: Ah, we had a… message from, ah, the Wright Valley, and they are clear over there.

- Mulgrew: Oh good.

- Collins: So if you can get us over that way…

- Mulgrew: No trouble.

- Collins: Right.

- Mulgrew: Taylor [Valley] on the right now.

- ?: Oh yeah.

- ?: Can we have a swap round now please?

- Cassin: I see vert speed…

- Mulgrew [PA]: This is Peter Mulgrew again, folks. I still can’t see very much at the moment. Keep you informed soon as I see something that gives me a clue as to where we are. I’ll let you know. Is that coming over…?

- ?: Yep.

- Collins: Two nine… two nine three oh… right.

- Cassin: Yep.

- Mulgrew [PA]: We’re going down in altitude now and it won’t be long before we get quite a good…

- Cassin: A thousand to go.

- Collins: OK. Alt nav track.

- Cassin: Vert speed.

- Collins: Speed…

- Cassin: Speed, I see.

- Brooks: Where’s Erebus in relation to us at the moment?

- ?: Left about four or five miles, about eleven o’ clock.

- ?: Yep.

- ?: Left, do you reckon?

- ?: Well… no… I think…

- ?: I’ve been looking for it.

- ?: I think it’ll be… er…

- Brooks: I’m just thinking of any high ground in the area, that’s all.

- Mulgrew: I think it’ll be left, yeah.

- Moloney: Yeah, I reckon about here.

- Mulgrew: Yes. No. No, I don’t really know.

- Mulgrew: That’s the edge.

- ?: Two thousand feet.

- Collins: Yep.

- Cassin: Yep.

- Brooks: Yeah, I just…

- Cassin: IAS hold.

- Brooks: …didn’t want to block the window too completely with it.

- ?: Oh yeah.

- Collins: You’ve got speed set up there anyway, haven’t you?

- Moloney: Alt cap.

- Collins: Speed, nav track alt, hold. We might have to… down to 1500 feet here, I think.

- Cassin: Yeah, OK. Probably see further in anyway.

- Cassin: Not too bad. I see vert speed for 1500 feet.

- Moloney: It’s not right. Yeah, bloody… spending a very long while on bloody instruments at this height, are you?

- Brooks: Alt cap.

- Mulgrew: Ross Island there.

- ?: Alt hold.

- Moloney: Yeah, yeah.

- Mulgrew: Erebus should be here.

- Cassin: Terrain. Fifteen hundred.

- ?: Capture.

- Cassin: Alt hold.

- Brooks: Hold both on nav track.

- Collins: Ah, we didn’t get that TACAN [tactical air navigation system] frequency, did we?

- Cassin: No.

- Brooks: Have we got the… on the aircraft?

- ?: Wasn’t the frequency 1-0-9-2?

- Cassin: Well, we think that’s what it is, but channel 29.

- Collins: Actually, those conditions don’t look very good at all.

- Mulgrew: No, they don’t. You’re down at one one four now, are you?

- Collins: 1500. What’s, um… have we got them on the tower?

- Cassin: No, I’ll try again.

- Moloney: Only got them on HF, that’s all.

- Collins: Try ’em again.

- Cassin: OK.

- Mulgrew: Looks like the egde of Ross Island there…

- Cassin: Mac Tower, ah, this is New Zealand 9-0-1 on 1-3-4-1, do you read?

- ?: Ah.

- Brooks: I don’t like this.

- Collins: Have you got anything from him?

- Cassin: No.

- Collins: We’re 26 miles north, we’ll have to climb out of this.

- ?: OK.

- Cassin: It’s clear on the right.

- Collins: Is it?

- Cassin: Yep.

- ?: You can see Ross Island.

- Cassin: You’re clear to turn right, there’s…

- Collins: No, negative.

- Cassin: …no high ground if you do a one-eighty.

- Ground Proximity Warning: Whoop! Whoop! Pull! Up! Whoop! Whoop!

- Brooks: Five hundred feet.

- Ground Proximity Warning: Pull! Up! Whoop! Whoop!

- Brooks: Four hundred feet…

- Ground Proximity Warning: Whoop! Whoop! Pull! Up! Whoop! Whoop!

- Collins: Go-around power, please.

- Ground Proximity Warning: Whoop! Whoop! Pull!

Ten minutes out.

Nine minutes.

Eight minutes.

Seven minutes.

Six minutes out.

Five minutes.

Four minutes.

Three.

[sound of altitude alert]

Two.

[sound of altitude alert]

One minute to impact.

Mulgrew thinks he sees Ross Island to the left; instead he sees an outcropping that marks the base of Mt. Erebus. With nothing on what seems to be the horizon, and no depth perception or forward-looking radar, there’s no reason for anyone to disagree with him.

[end of recording]

According to an archived Aviation Week article:

According to the American Meteorological Society, in a whiteout, “Neither shadows, horizon nor clouds are discernible; sense of depth or orientation is lost; only very dark, nearby objects can be seen.” The result is plenty of vertigo-inducing, sensor illusions when you’re trying to make the transition between IMC and VMC on takeoff or landing. Your eyes don’t focus on anything in particular. Objects that suddenly appear may not be visible because you’re not focusing on anything in the background.

This is known as sector whiteout and it was a “major contributing factor” in a DC-10 controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accident in 1979 on Mount Erebus in Antarctica, according to Human Factors for Aviation, a basic handbook published by Transport Canada. The crew of Air New Zealand Flight 901 lost visual reference to the horizon and surface obstructions even though the prevailing visibility was in excess of 40 miles.

…which wouldn’t have killed anyone, had the plane not been pre-programmed, without the flight crew’s knowledge, to go somewhere where there were surface obstructions. Collins’ and Cassin’s flying would’ve been perfectly safe for McMurdo Sound, which is where they expected to be. Instead, they took their plane on a series of maneuvers that slammed it into Mt. Erebus at 500 mph+. With over half of the necessary fuel for the trip still in the plane’s tanks, the plane experienced not just disintegration, but immolation. Everyone was killed instantly. Some of the remains were so badly charred that they could never be identified.

Since flight 901 was a sightseeing flight, the abundance of passengers naturally brought an abundance of cameras. Still photos and short stretches of movie film were recovered from the wreckage and developed, showing clear skies on either side of the plane.

The first official inquiry into the accident crucified the pilots. There’s a sizeable chunk of the Kiwi population that still feels this was the cause. It’s easy to feel like the crew is incompetent – good grief, their reactions are totally inappropriate for the crew of an airplane zooming into a mountain! – until you remember that they didn’t know their plane was in that predicament. There was no GPS or constant satellite tracking back then. Their plane had been programmed to go to the wrong place – and the crew had been programmed to look for landmarks that wouldn’t be in that place, preventing them from latching onto any fleeting visual clues that were there.

The second report exonerated the crew and harshly admonished the airline for putting the plane on the wrong flight path from the word go. All hell then proceeded to break loose among those who’d never even left the ground.

Tomorrow, I’ll bring this in for a landing (a safe one, if you’re extremely lucky!), and relate this to organizational structure and responsibility in the here and now.

+ There are no comments

Add yours