Previously, on Scribblings… this week I’m writing about Air New Zealand flight TE901, an Auckland-to-Antarctica round trip sightseeing flight that never returned home, only to be found later in the form of wreckage on the slopes of an active volcano, with all hands lost.

In the absence of survivors, and with nothing immediately jumping out as a red flag on the cockpit voice recorder, investigators and the public were left scratching their heads. Theories ranged from mild to wild. Had yet another DC-10 gone to pieces? (Though later established as a safe and reliable aircraft, the still-young DC-10 didn’t have a perfect batting average at the time, with one nightmare-inducing, all-hands-lost crash on the books for 1979 already.) Had the plane gotten too close to Erebus as the volcano erupted? (Erebus is, after all, one of the most consistently active volcanoes on Earth, even if you never hear about that because of where it is.) Had freak weather conditions blinded the crew and/or their instruments? (Surely not.)

The conclusions of the two investigations into the fate of flight 901 couldn’t have been further apart if they’d tried. The first investigation claimed pilot error: the pilots lost track of where they were, descended into a cloud bank, and slammed into a mountain. The second investigation concluded that the pilots didn’t have a chance in hell: the plane’s autonavigation – which flew most of the tiringly long flight for them – was misprogrammed from the outset, and then disastrously “corrected” without the crew’s knowledge. And they slammed into a mountain.

Same result, but what happened?

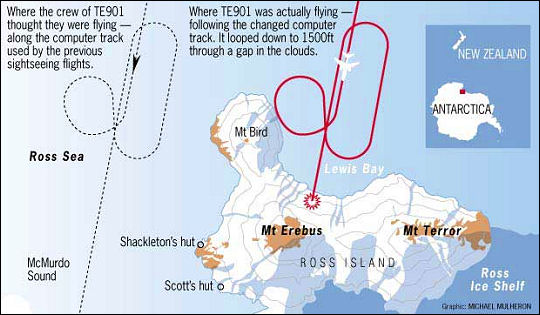

An incident that was actually mentioned in both investigations – but with wildly varying amounts of emphasis placed on it – was the misprogramming of the plane’s navigation system. There had been a long-standing mistake in the numerical entry of the navigation plot to McMurdo Sound which had been accepted by all of the previous pilots flying the Antarctic sightseeing route because it had actually made the flight path safer. The flight path took the planes down the flat, level expanse of McMurdo Sound, leaving Ross Island and its highest peak, Mt. Erebus, safely to their left. The flight path, with a mistake in its numerical input, made the flights safer by steering clear of high ground until or unless the pilots took over on manual.

These being sightseeing flights, taking over on manual was expected. Though not encouraged for planes the size of a DC-10, it was routine – hell, it was advertised in the brochures for the Antarctic flights – for the sightseeing flights to descend to 1,500 feet to give passengers a clear view of McMurdo Base and the surrounding terrain, even flying over or around the peak of Mt. Erebus in some cases (which is why the eruption theory even existed). After spending an hour or two providing what basically amounted to photo ops at close to the minimum speed needed to keep the plane airborne, which was still in the vicinity of 500+ miles per hour, the plane would loop around and return to New Zealand, with much of the return flight handed back over to autopilot.

The original navigation program was intended to take the planes directly over the summit of Erebus – at a safe altitude, naturally – but the pilots didn’t complain about the data entry error which put the plane back under their control over a 40-mile-wide stretch of flat ice rather than over an almost 13,000-foot volcano.

In any case, most of the previous flights’ pilots had switched off autopilot early and done their own thing. Flat ice plains weren’t too sexy. The ticketholders were paying for smooth precision flying over amazing terrain. It became standard operating procedure, therefore, for the pilots to do their own thing.

As innocuous as it sounds, this was the first step toward the disaster of flight 901.

19 days before the flight to Antarctica, Capt. Jim Collins and his co-pilot, Greg Cassin, both experienced airline pilots with ample time flying the DC-10, attended a flight briefing which essentially confirmed the long-standing error: autonavigation would bring the plane to McMurdo Sound, where specific land masses, features and landmarks would be visible. At that point, Collins and Cassin would be able to take it on manual, drop the plane’s altitude, and give the airline’s paying customers the show they’d paid their money for.

Mere hours before the flight, someone in Air New Zealand’s navigational section “corrected” the autonavigation program. No one had complained about the error, but it had still been flagged as an error by the pilot of a previous flight. Why not fix it?

But since it had become standard operating procedure to disengage autopilot short of the final waypoint in the navigational program – basically, because everyone in the company was doing their own thing – the person responsible for changing the coordinates of the nav program did his own thing: he didn’t notify the flight crew. TE901 took off from Auckland, and once the manual flying to get the plane from the tarmac to safe cruising speed and altitude had been accomplished, Collins did what every single one of his predecessors had done: he handed the flight over to the autopilot.

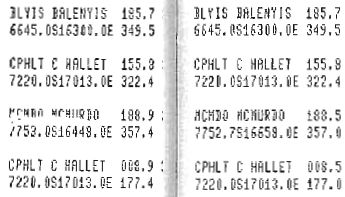

On the left, you’ll see the navigation program used by previous flights. On the right, you’ll see the navigation program fed into the computer aboard flight 901.

This resulted in a change of the entire angle of approach for flight 901. The change from 16448.0 east to 16658.0 east looks small at first when plotted on a map, but when plotted out to its logical, mathematical conclusion, the result was as follows (map originally published at stuff.co.nz):

Since no one notified Collins and Cassin, they were – in their own way – “programmed” to expect a flight into McMurdo Sound.

Pilots did their own thing on previous flights by changing course early. A navigational engineer did his own thing by “fixing” the program flying the plane, assuming that the pilots would keep doing their own thing; the endpoint wouldn’t matter because autopilot would have been disengaged by then. Right?

Wrong. Oh so wrong. So many people got it wrong, but took it upon themselves to fix it. Because it feels good to be self-reliant and be the guy who fixes the problem, right? Pat yourself on the back.

And then you either make enough noise to have the error corrected at the institutional level, with proper notification given to all affected parties, to protect the next pilot…

…or you say a prayer for the next pilot it’s going to happen to.

Tomorrow’s entry: the crew continues flying a textbook flight, unaware that the textbook has been switched out on them. Their only warning of impending doom? The words “PULL! UP!”

[…] flying the artcic sightseeing route made no complaint about a mistake in the flight plot, as it resulted in the flight actually being safer. The mistaken coordinates were entered just over a year before, when Air New Zealand’s routes […]