Eight years ago, I wrote a serious, melancholic diary about my own close brush with a tornado. And I was truly serious (and melancholic) about that at the time, and indeed about many things. But on the eve of a new storm season, having moved away from Tornado Alley and back again, it seems like an excellent time to revisit this subject.

It’s not that I’m no longer afraid of tornado warnings. Au contraire. Now that I’m a homeowner, I’m bloody terrified of them.

2003 was a uniquely bad weather year; May of that year saw my area blanketed with almost daily storm watches and warnings, and by the end of the month, my wife and our cats and I had hit the closet something like seven or eight times. “Hitting the closet,” in this context, meant corralling the three cats into their individual carriers, lugging those carriers down to the hall closet of our rental house, and cramming ourselves in there as well, with a battery-operated radio and a flashlight or two to boot. This can be a somewhat unnerving affair because neither the love of my life nor myself can exactly be described as svelte, and a tower of cats three carriers high takes up a lot of space in a coat closet. It gets warm in there very quick.

It also doesn’t help that the local broadcast media is loaded down with meteorological doomsayers. Far be it from me to suggest that an actual threat should be downplayed, but these guys elevate the art of being Chicken Little to a new height – or a new low. In Tornado Alley, an incoming severe storm is cause for interruption of programming, and in Tornado Alley – and I realize that the following may be a hard concept for those who don’t live here to swallow – a weathercaster, whether on TV or radio, can literally be on the air talking for an hour or two hours at a time until the most constant, persistent core of the storm has left the viewing area. There’s no shortage of information, storm spotter call-ins, and viewer call-ins, and there’s also no shortage of assumption that it’s the worst possible scenario. At night, it’s really a tough call, because you can’t see the damn thing as it’s bearing down on you. This, I know better than most. I don’t envy these people their jobs (indeed, I’ve done that job in the past), but I also don’t envy nerve-wracked viewers and listeners who don’t detect that there’s a wee bit of grandstanding going on. Make one call right, help people out, and you can become a local legend. Overplay it consistently, and you’re the boy – or girl – who cried wolf.

Now, imagine being in that closet on an average of four to six hours a week for a month. After the first three consecutive nights of closet sitting, we eventually left the stack of three cat carriers in the closet, with their doors open – the Kittycat Hilton. After a couple more nights of tornado warnings, including one night where we literally heard the airborne tornado go over the house with an unearthly, subsonic, howling, last-of-the-bathwater-going-down-the-drain-sound-pitched-down-nineteen-octaves moan, the cats learned that the sound of sirens meant that they should proceed in an orderly fashion down the hall and jump into their appointed carriers without us having to pick them up and shove them into the carriers anymore.

One really can get the impression that Someone Up There has it in for you after a few nights of that.

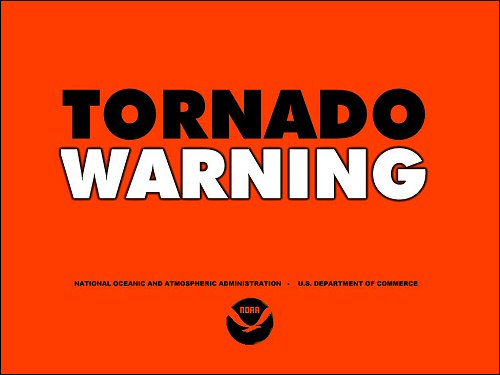

But there are warnings out there. Why, in my youth, I was fucking terrified by the sight of the Red Screen Of Death. No, not a fatal exception at 0EA22F requiring me to close my application and losing all unsaved information. The Red Screen Of Death was something that could cut into my cartoons, or worse yet into Buck Rogers, at any time, instilling true terror. In the 70s and early 80s, local stations all had a standardized “key slide” (a screen-filling still graphic referred to in modern television parlance as a “stillstore”) for weather warnings around here, and there was none of this urgent music and enough-time-to-remind-you-that-the-following-weather-bulletin-was-brought-to-you-by-a-local-Ford-dealership. No, my friends, it came without warning with the horrifyingly blaring tone of an EBS tone, and it looked like this:

To understand the inherent terror of this sight, one must understand that there was a hierarchy of such graphics, each progressively deepening down the warm side of the color wheel, yellow edging toward orange, orange descending into an angry red. The text got correspondingly larger with the level of threat being announced. Tom Ridge and John Ashcroft would have a field day with this kind of system in place.

To understand why these things – and, even to this day, to a certain extent just the color red itself – are so ingrained into my psyche as a Bad Thing, one must take into account one occasion when I was staying at my grandmother’s house after school. She had gone somewhere on a very brief errand on a rainy day, leaving me in the hands of Scooby Doo, a large glass of Dr. Pepper, and two deliciously soppy grilled cheese sandwiches.

And then the Red Screen Of Death had the audacity to interrupt my cartoon.

And then, before Forrest John, the voice of Fort Smith’s now-defunct National Weather Service office, had a chance to give me further occasion to shit myself, an almighty thunderclap and bolt of lightning hit somewhere very close to the house. And then the power was gone and the wind picked up and the hail began pelting the house and I was under some piece of furniture crying, despite being six or seven or so – past the generally accepted age at which a child, especially a male child, is expected respond that way.

And then, before Forrest John, the voice of Fort Smith’s now-defunct National Weather Service office, had a chance to give me further occasion to shit myself, an almighty thunderclap and bolt of lightning hit somewhere very close to the house. And then the power was gone and the wind picked up and the hail began pelting the house and I was under some piece of furniture crying, despite being six or seven or so – past the generally accepted age at which a child, especially a male child, is expected respond that way.

Yeah, somehow that screen permanently etched itself into my memory. I couldn’t really tell you how.

(By the way, the screens you see above are very accurate recreations I cobbled together in Paint Shop Pro after failing to find any evidence of the real key slides anywhere on the Internet. If anyone out there, especially fellow or former broadcast professionals with experience of working in Tornado Alley, can point me toward the real things, please give me a shout. I’m enough of a bad weather geek to have the originals scanned, digitally enshrine them and return the originals to you.)

(By the way, the screens you see above are very accurate recreations I cobbled together in Paint Shop Pro after failing to find any evidence of the real key slides anywhere on the Internet. If anyone out there, especially fellow or former broadcast professionals with experience of working in Tornado Alley, can point me toward the real things, please give me a shout. I’m enough of a bad weather geek to have the originals scanned, digitally enshrine them and return the originals to you.)

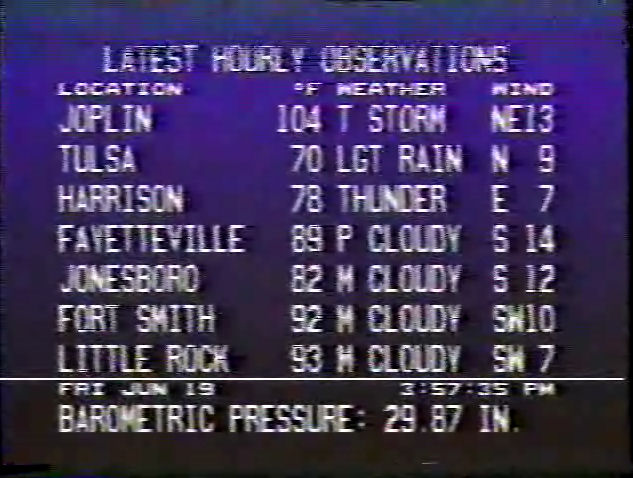

Nowadays, I scare the dickens out of myself, with much more technologically advanced means.

Between the months of March and mid-June, I make at least one daily visit to the Storm Predication Center page at the National Weather Service’s web site. They feature helpful graphic representations of their forecasts, accompanied by far more cryptic textual analyses of the conditions that might cause the sky to try to eat my house. With time, I’ve actually begun to figure out what some of these things actually say. Here’s a quick translation chart.

The weather alert radio is a vital tool as well, especially now that I live, technically, out in the boonies. There are no sirens out here, and in fact my new home has no west-facing windows, which was really my biggest quibble with buying the place. Why? This stuff almost always moves in from the northwest or, more likely, the southwest. Death stalks the land, and he walks first through Oklahoma. (Fine by me, really. I just wish he’d get his belly full before crossing the border. But I kid the fine people of eastern Oklahoma, my dad and my older sister among them.) The weather alert radio, for those of you not accustomed to our backward ways here, emits a shrill signal when triggered by the National Weather Service’s radio relays. You have approximately 30 seconds to reach the radio and hit a button which will allow the actual Weather Service Signal to be heard, which will include the location, duration and nature of the warning or watch being issued. The Red Screen Of Death is the direct antecedant of this technology, but I handle it fairly calmly unless things are cookin’ in the atmospheric cauldron over my particlar tiny slice of this planet.

The Internet, if you can keep the damned computer online without frying it in its own fat (or yours, if you’re standing too near it when lightning strikes), is a handy tool because of live updated online radars. Sure, TV stations have these too, but the Internet makes it possible for me to just cut to the chase and look at the radar without the attendant histrionics. Green blobs are rain. Yellow blows are heavier rain. Orange blobs probably freeze the rain into little pellets of hail and chuck them at you violently. Red blobs deservedly conjure up all my old fears about full screens of that color. But little spiral galaxies of red and green intertwining into a vortex are the worst news, for that’s something small, fast-moving, and violently rotating. That’s the radar signature of the tornado – in technical terms, a “hook echo return.” It’s where the volume of airborne liquid at that precise location is moving away from – and simultaneously toward – the radar at such a velocity that it indicates very fast rotation. It may or may not be on the ground, and that’s where ground-based spotters come in. God bless these suicidal maniacs, they actually get out in front of the damned thing and keep an eye on it, so long as it isn’t actively trying to eat them. They’re often well-trained ham radio operators, but they also know that being in the wrong place at the wrong time could turn them into spiral-cut hams.

And ultimately, all joking aside, it’s still scary as hell. Now that I own my own home, the next time a tornado warning is issued for Crawford County, and the cities of Alma and Mountainburg are in the path of the storm, I’ll be torn between a panic (for obvious reasons) and a rage (that anything would dare to violate the sanctity of my home). And that really sums up the Tornado Alley experience. When you’ve been under one kind of a watch or another for days on end, it wears you down; even in the privacy and safety of your own home, you feel like you’re about as safe as someone sitting on a street corner in downtown Baghdad. It also often means long work hours for me and everyone else in the broadcast biz, which has its own unnerving effect (especially when, as was the case with the first tornado warning of the season this year, a warning is issued for the vicinity of my home, and something has been spotted on something other than radar, and I’m stuck at work and can’t do anything about it.

Those are the times when I would give anything to be at home, right in the path of it. Drinking Dr. Pepper and eating grilled cheese sandwiches. And at least knowing how bad it is. Because sometimes not knowing is even more nerve-wracking than the knowing.

Skip to content

Being the blog of theLogBook.com's webmaster, Earl Green

You May Also Like:

Categories

Changes in fortune

Categories

The Little Green Men on closeness

Categories

The Little Green Men on hippo feasts

Categories

Conversations with Little C, day 990

Categories

How’s the weather 30 years ago?

Categories

+ There are no comments

Add yours