Dr. Claudia Alexander, Galileo project manager, dies

Dr. Claudia Alexander dies at the age of 56, while still serving as the chief scientist of a suite of U.S.-provided instruments aboard ESA’s history-making Rosetta mission. Renowned as one of JPL’s finest research scientists, she was a member of the Galileo plasma instrument science team before becoming, by the mission’s end in 2003, the project manager of that mission to Jupiter.

Dr. Claudia Alexander dies at the age of 56, while still serving as the chief scientist of a suite of U.S.-provided instruments aboard ESA’s history-making Rosetta mission. Renowned as one of JPL’s finest research scientists, she was a member of the Galileo plasma instrument science team before becoming, by the mission’s end in 2003, the project manager of that mission to Jupiter.

Galileo’s mission ends

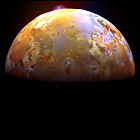

The mission of the unmanned space probe Galileo ends in the clouds of the giant planet Jupiter, which it has orbited for eight years. Even as Galileo plunges toward Jupiter, it detects and reports evidence of a thin ring sharing the orbit of the small moon Amalthea, and then disintegrates as it falls into Jupiter. NASA has opted to send Galileo to its destruction, rather than risking a collision with Europa, which may harbor some of the ingredients necessary for life and might be contaminated if Galileo impacted it; Galileo’s mission was extended three times, with the vehicle lasting six years longer than anticipated in the original mission plan’s estimates, which included for the harsh radiation environment of Jupiter as a factor in expecting only a two-year mission.

The mission of the unmanned space probe Galileo ends in the clouds of the giant planet Jupiter, which it has orbited for eight years. Even as Galileo plunges toward Jupiter, it detects and reports evidence of a thin ring sharing the orbit of the small moon Amalthea, and then disintegrates as it falls into Jupiter. NASA has opted to send Galileo to its destruction, rather than risking a collision with Europa, which may harbor some of the ingredients necessary for life and might be contaminated if Galileo impacted it; Galileo’s mission was extended three times, with the vehicle lasting six years longer than anticipated in the original mission plan’s estimates, which included for the harsh radiation environment of Jupiter as a factor in expecting only a two-year mission.

Galileo lives!

NASA and JPL ground controllers coax the radiation-damaged tape recorder built into the Galileo probe into working again, finally allowing several weeks worth of scientific data to be replayed to Earth. The damage was suffered during Galileo’s closest pass by Jupiter to study the tiny moon Amalthea the previous month. With layoffs looming for many of Galileo’s ground control staff in early 2003, this is Galileo’s last chance to relay its scientific findings back to Earth. It is on a trajectory that will end its mission by plunging into Jupiter in 2003.

NASA and JPL ground controllers coax the radiation-damaged tape recorder built into the Galileo probe into working again, finally allowing several weeks worth of scientific data to be replayed to Earth. The damage was suffered during Galileo’s closest pass by Jupiter to study the tiny moon Amalthea the previous month. With layoffs looming for many of Galileo’s ground control staff in early 2003, this is Galileo’s last chance to relay its scientific findings back to Earth. It is on a trajectory that will end its mission by plunging into Jupiter in 2003.

Galileo takes the Amalthea plunge

Nearing the end of its fuel supply, NASA’s Galileo probe passes one of Jupiter’s innermost moons, tiny, asteroid-like Amalthea, at a distance of less than 100 miles, coming closer to Jupiter and its belts of intense radiation than ever before. This final flyby of a Jovian moon is a punishing one for Galileo: the failure of Galileo’s main antenna dish after its 1989 launch has forced the robotic explorer to store its findings on tape for later playback to Earth at a low bit rate, but in this case roughly half of Galileo’s measurements of the highly charged environment near Jupiter are lost to radiation-induced failure of the tape recording system. The intense radiation also causes enough faults in Galileo’s main computer that the probe puts itself in a failsafe mode and “sleeps” until further commands are received from Earth hours later.

Nearing the end of its fuel supply, NASA’s Galileo probe passes one of Jupiter’s innermost moons, tiny, asteroid-like Amalthea, at a distance of less than 100 miles, coming closer to Jupiter and its belts of intense radiation than ever before. This final flyby of a Jovian moon is a punishing one for Galileo: the failure of Galileo’s main antenna dish after its 1989 launch has forced the robotic explorer to store its findings on tape for later playback to Earth at a low bit rate, but in this case roughly half of Galileo’s measurements of the highly charged environment near Jupiter are lost to radiation-induced failure of the tape recording system. The intense radiation also causes enough faults in Galileo’s main computer that the probe puts itself in a failsafe mode and “sleeps” until further commands are received from Earth hours later.

Galileo’s close look at Io’s volcanoes

NASA/JPL’s Galileo unmanned space probe makes the closest flybys yet of Io, the volcanically hyperactive moon of Jupiter which made headlines when Voyager scientists spotted an eruption in 1980. The new images give the best view yet of Io’s inhospitable surface, including a volcanic crater, 47 miles across, named after the Brazilian god of thunder, Tupan Patera – an eye-searingly colorful region even in natural light.

NASA/JPL’s Galileo unmanned space probe makes the closest flybys yet of Io, the volcanically hyperactive moon of Jupiter which made headlines when Voyager scientists spotted an eruption in 1980. The new images give the best view yet of Io’s inhospitable surface, including a volcanic crater, 47 miles across, named after the Brazilian god of thunder, Tupan Patera – an eye-searingly colorful region even in natural light.

Mission accomplished again! Now do more.

Completing its extended two-year tour of Jupiter and its intriguing moons Io and Europa, NASA’s Galileo robotic probe is given another extension, this time called the Galileo Millennium Mission. Highlights are expected to include observing Jupiter in tandem with the Cassini unmanned probe, which will swing by Jupiter in 2000 to gain a gravity assist en route to its own final target, Saturn. Galileo will also resume its exploration of the major Jovian moon Ganymede, the solar system’s largest satellite.

Completing its extended two-year tour of Jupiter and its intriguing moons Io and Europa, NASA’s Galileo robotic probe is given another extension, this time called the Galileo Millennium Mission. Highlights are expected to include observing Jupiter in tandem with the Cassini unmanned probe, which will swing by Jupiter in 2000 to gain a gravity assist en route to its own final target, Saturn. Galileo will also resume its exploration of the major Jovian moon Ganymede, the solar system’s largest satellite.

Galileo vs. the Volcano

NASA/JPL’s unmanned Galileo space probe buzzes Jupiter’s volcanically active moon Io, zipping directly over one of its most active volcanic regions at an altitude of only 380 miles, Galileo’s closest Io flyby to date. But this close encounter, and the fate of Galileo itself, had been in doubt just hours before the flyby: entering Jupiter’s most intense radiation environment, Galileo had entered a failsafe mode in which the spacecraft shuts down until further commands are received from Earth. Ground controllers, called in to work emergency hours on a Sunday, revive Galileo a mere two hours before its close pass by Io.

NASA/JPL’s unmanned Galileo space probe buzzes Jupiter’s volcanically active moon Io, zipping directly over one of its most active volcanic regions at an altitude of only 380 miles, Galileo’s closest Io flyby to date. But this close encounter, and the fate of Galileo itself, had been in doubt just hours before the flyby: entering Jupiter’s most intense radiation environment, Galileo had entered a failsafe mode in which the spacecraft shuts down until further commands are received from Earth. Ground controllers, called in to work emergency hours on a Sunday, revive Galileo a mere two hours before its close pass by Io.

Galileo and the battery acid of Europa

A long-standing mystery of one of the moons of Jupiter is solved, opening many more questions. Data gathered by the Galileo unmanned orbiter reveals that a previously unidentifiable substance on Europa’s surface is sulfuric acid, a compound used as battery acid on Earth. Scientists quickly split into two camps on the origins of the acid: it may be welling up from inside Europa, or it may be volcanic material ejected from Io and then deposited on Europa as the moons’ orbits occasionally bring them into conjunction. Though the presence of sulfuric acid initially dashes hopes of finding life on Europa, the possibility is not completely ruled out by this finding.

A long-standing mystery of one of the moons of Jupiter is solved, opening many more questions. Data gathered by the Galileo unmanned orbiter reveals that a previously unidentifiable substance on Europa’s surface is sulfuric acid, a compound used as battery acid on Earth. Scientists quickly split into two camps on the origins of the acid: it may be welling up from inside Europa, or it may be volcanic material ejected from Io and then deposited on Europa as the moons’ orbits occasionally bring them into conjunction. Though the presence of sulfuric acid initially dashes hopes of finding life on Europa, the possibility is not completely ruled out by this finding.

Galileo and the strange chemistry of Europa

NASA scientists announce a startling find on one of Jupiter’s moons: a chemical which must be manufactured on Earth occurs naturally on the surface of Europa. The Galileo orbiter detects naturally-occurring hydrogren peroxide on the surface of the icy moon (a surface which most planetary scientists now believe covers an ocean of water or “slush” just beneath the crust), probably caused by the constant bombardment of radiation-charged particles from Jupiter itself. The hydrogen peroxide on Europa is also found to be very short-lived, quickly breaking down into gaseous oxygen and hydrogen.

NASA scientists announce a startling find on one of Jupiter’s moons: a chemical which must be manufactured on Earth occurs naturally on the surface of Europa. The Galileo orbiter detects naturally-occurring hydrogren peroxide on the surface of the icy moon (a surface which most planetary scientists now believe covers an ocean of water or “slush” just beneath the crust), probably caused by the constant bombardment of radiation-charged particles from Jupiter itself. The hydrogen peroxide on Europa is also found to be very short-lived, quickly breaking down into gaseous oxygen and hydrogen.

Galileo and the atmosphere of Callisto

NASA reveals recent findings from the unmanned Galileo orbiter touring Jupiter and its moons, including the discovery of a tenuous atmosphere surrounding the outermost large moon of Jupiter, Callisto. The thin layer of carbon dioxide surrounding Callisto completes the set: Galileo has detected an atmosphere of one kind or another around each of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, some of which are large enough to be planets. As for how the atmosphere is sustained in the extremely hostile environment around Jupiter, scientists speculate that the CO2 could be emitted from beneath Callisto’s own crust.

NASA reveals recent findings from the unmanned Galileo orbiter touring Jupiter and its moons, including the discovery of a tenuous atmosphere surrounding the outermost large moon of Jupiter, Callisto. The thin layer of carbon dioxide surrounding Callisto completes the set: Galileo has detected an atmosphere of one kind or another around each of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, some of which are large enough to be planets. As for how the atmosphere is sustained in the extremely hostile environment around Jupiter, scientists speculate that the CO2 could be emitted from beneath Callisto’s own crust.

Galileo and the oceans of Callisto

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Galileo makes a remarkable find at Callisto, the outermost of Jupiter’s four large “Galilean” moons: evidence that a saltwater ocean may lie beneath the moon’s pockmarked surface. Even more unusually, it may be the catalyst for Callisto’s magnetic field (a rarity for a satellite – not even all of the solar system’s planets have magnetic fields). Galileo’s instruments raise the possibility that the subsurface ocean may be conducting electricity and helping to generate that field (which current scientific models say Callisto should be too small to generate on its own). Scientists do not, however, believe that Callisto is a strong candidate to support life, unlike Europa.

The unmanned NASA/JPL space probe Galileo makes a remarkable find at Callisto, the outermost of Jupiter’s four large “Galilean” moons: evidence that a saltwater ocean may lie beneath the moon’s pockmarked surface. Even more unusually, it may be the catalyst for Callisto’s magnetic field (a rarity for a satellite – not even all of the solar system’s planets have magnetic fields). Galileo’s instruments raise the possibility that the subsurface ocean may be conducting electricity and helping to generate that field (which current scientific models say Callisto should be too small to generate on its own). Scientists do not, however, believe that Callisto is a strong candidate to support life, unlike Europa.

Mission accomplished! Now keep going.

Beating the odds imposed upon it by the unforgiving environment around the planet Jupiter and its major moons, and engineering challenges such as a high-gain antenna that never unfurled properly after its 1989 launch, NASA’s Galileo space probe completes its two-year mission. Since the spacecraft is still intact and reasonably healthy, NASA gains a two-year extension, which it calls the Galileo Europa Mission, focusing on the two innermost large moons, icy Europa and volcanic Io. Trajectories are planned to fly Galileo even closer to these moons than ever before, though the harsh radiation zone around Jupiter itself could fry Galileo’s main computer and end the mission at any time.

Beating the odds imposed upon it by the unforgiving environment around the planet Jupiter and its major moons, and engineering challenges such as a high-gain antenna that never unfurled properly after its 1989 launch, NASA’s Galileo space probe completes its two-year mission. Since the spacecraft is still intact and reasonably healthy, NASA gains a two-year extension, which it calls the Galileo Europa Mission, focusing on the two innermost large moons, icy Europa and volcanic Io. Trajectories are planned to fly Galileo even closer to these moons than ever before, though the harsh radiation zone around Jupiter itself could fry Galileo’s main computer and end the mission at any time.

Galileo takes the plunge

After five months of independent flight, the Galileo atmospheric probe slams into the atmosphere of giant planet Jupiter at a speed over 100,000mph, burrowing over a hundred miles into the huge planet’s dense atmosphere before the heat of entry and the atmospheric pressure crush the probe. Deploying a parachute to slow its descent, the probe survives for nearly an hour, its sensors finding a surprisingly dry atmosphere. As it plummets toward the center of Jupiter, the Galileo probe registers 450mph winds, but never finds any hints of anything resembling a solid surface. The sum total of the probe’s sensor readings – the entirety of our data gathered directly within the atmosphere of Jupiter – tops out at 460 kilobytes of data.

After five months of independent flight, the Galileo atmospheric probe slams into the atmosphere of giant planet Jupiter at a speed over 100,000mph, burrowing over a hundred miles into the huge planet’s dense atmosphere before the heat of entry and the atmospheric pressure crush the probe. Deploying a parachute to slow its descent, the probe survives for nearly an hour, its sensors finding a surprisingly dry atmosphere. As it plummets toward the center of Jupiter, the Galileo probe registers 450mph winds, but never finds any hints of anything resembling a solid surface. The sum total of the probe’s sensor readings – the entirety of our data gathered directly within the atmosphere of Jupiter – tops out at 460 kilobytes of data.

Jupiter eats a comet

Its collision with the solar system’s largest planet predicted over a year in advance, the fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 begin impacting Jupiter’s atmosphere in an astronomical event lasting six days. With Earth-based telescopes watching, as well as cameras and instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope, Galileo and even Voyager 2, huge explosions are witnessed as the cometary chunks slam into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere at over 200,000 miles per hour, leaving dark “scars” larger than the diameter of Earth visible on the planet’s atmosphere and releasing more heat than the surface of the sun. Galileo is still over a year away from arriving at Jupiter.

Its collision with the solar system’s largest planet predicted over a year in advance, the fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 begin impacting Jupiter’s atmosphere in an astronomical event lasting six days. With Earth-based telescopes watching, as well as cameras and instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope, Galileo and even Voyager 2, huge explosions are witnessed as the cometary chunks slam into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere at over 200,000 miles per hour, leaving dark “scars” larger than the diameter of Earth visible on the planet’s atmosphere and releasing more heat than the surface of the sun. Galileo is still over a year away from arriving at Jupiter.

Galileo eyes Ida

Bound for Jupiter, the NASA/JPL unmanned space probe Galileo swings past the asteroid Ida, discovering – for the first time – an asteroid with its own satellite, a tiny body orbiting Ida. The satellite is later named Dactyl. This is only the second asteroid to be visited by a spacecraft from Earth, and Ida also marks Galileo’s last visit to a body in the solar system before a two-year cruise toward Jupiter.

Bound for Jupiter, the NASA/JPL unmanned space probe Galileo swings past the asteroid Ida, discovering – for the first time – an asteroid with its own satellite, a tiny body orbiting Ida. The satellite is later named Dactyl. This is only the second asteroid to be visited by a spacecraft from Earth, and Ida also marks Galileo’s last visit to a body in the solar system before a two-year cruise toward Jupiter.

Galileo’s last visit home

Catching the last gravity assist on its four-year “VEEGA” tour of the inner solar system, NASA/JPL’s Galileo spacecraft swings past Earth one last time, conducting further tests of its imaging system and other instruments by examining Earth and its moon. Galileo now sets its sights on the outer solar system, where it will take up an orbit around giant planet Jupiter in 1995, studing the planet and its atmosphere, its moons, and its unfriendly-to-spacecraft radiation environment. Efforts to release the vehicle’s stuck high-gain antenna continue, though NASA admits that, within a few months, they will have to begin planning for a mission that can only make use of the low-bit-rate medium-gain antenna.

Catching the last gravity assist on its four-year “VEEGA” tour of the inner solar system, NASA/JPL’s Galileo spacecraft swings past Earth one last time, conducting further tests of its imaging system and other instruments by examining Earth and its moon. Galileo now sets its sights on the outer solar system, where it will take up an orbit around giant planet Jupiter in 1995, studing the planet and its atmosphere, its moons, and its unfriendly-to-spacecraft radiation environment. Efforts to release the vehicle’s stuck high-gain antenna continue, though NASA admits that, within a few months, they will have to begin planning for a mission that can only make use of the low-bit-rate medium-gain antenna.

Galileo gawks at Gaspra

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe, looping repeatedly through the inner solar system to gain a speed boost from a series of gravity assists from Earth and Venus, passes the asteroid 951 Gaspra, the first human-made spacecraft to visit such a body. Where humanity’s previous knowledge of asteroids was limited at best, Galileo’s findings are startling, with photos showing a small rocky body pummeled by ancient impacts, almost to the point of shattering it. Also discovered is a magnetic field generated by the core of the asteroid itself, something planetary scientists did not expect to find at all. Galileo will loop back toward Earth, picking up a critical speed boost to Jupiter from one last flyby of its home planet.

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe, looping repeatedly through the inner solar system to gain a speed boost from a series of gravity assists from Earth and Venus, passes the asteroid 951 Gaspra, the first human-made spacecraft to visit such a body. Where humanity’s previous knowledge of asteroids was limited at best, Galileo’s findings are startling, with photos showing a small rocky body pummeled by ancient impacts, almost to the point of shattering it. Also discovered is a magnetic field generated by the core of the asteroid itself, something planetary scientists did not expect to find at all. Galileo will loop back toward Earth, picking up a critical speed boost to Jupiter from one last flyby of its home planet.

Galileo’s antenna problem

Launched in 1989 via Space Shuttle, the unmanned Galileo probe reveals a significant technical problem during its first flyby of Earth: the umbrella-like high-gain antenna, allowing it to send its observations of Jupiter and its moons back to Earth at high speed, is stuck in a partly-open, partly-closed configuration that prevents its use. Ground engineers at JPL have to devise data compression schemes, and a tight record/playback schedule, that will allow Galileo to take all of its planned observations and send them back to Earth at a lower bit rate than planned. It is theorized that the long delays in Galileo’s launch – the probe was ready for launch in 1982 but had to wait through delays in the early shuttle program and was then kept in storage in the aftermath of the Challenger disaster – allowed the antenna’s lubricant to dry up. Galileo won’t reach its target planet, Jupiter, until 1995.

Launched in 1989 via Space Shuttle, the unmanned Galileo probe reveals a significant technical problem during its first flyby of Earth: the umbrella-like high-gain antenna, allowing it to send its observations of Jupiter and its moons back to Earth at high speed, is stuck in a partly-open, partly-closed configuration that prevents its use. Ground engineers at JPL have to devise data compression schemes, and a tight record/playback schedule, that will allow Galileo to take all of its planned observations and send them back to Earth at a lower bit rate than planned. It is theorized that the long delays in Galileo’s launch – the probe was ready for launch in 1982 but had to wait through delays in the early shuttle program and was then kept in storage in the aftermath of the Challenger disaster – allowed the antenna’s lubricant to dry up. Galileo won’t reach its target planet, Jupiter, until 1995.

Galileo visits a small blue planet

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe reaches the second destination on the lengthy “VEEGA” (Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist) flight path that will eventually take it to Jupiter. This leg of Galileo’s journey brings it back to its home planet, Earth, where crystal-clear images of the planet are obtained from the perspective of a passing spacecraft. Galileo will loop past Earth once more at a later date en route to Jupiter.

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe reaches the second destination on the lengthy “VEEGA” (Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist) flight path that will eventually take it to Jupiter. This leg of Galileo’s journey brings it back to its home planet, Earth, where crystal-clear images of the planet are obtained from the perspective of a passing spacecraft. Galileo will loop past Earth once more at a later date en route to Jupiter.

Galileo at Venus

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe – eventually bound for Jupiter – reaches the first destination on its looping “VEEGA” (Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist) trajectory, the planet Venus. This flyby of Venus allows for testing of Galileo’s cameras and other science instruments, offering the first near-infrared views of the planet’s dense clouds, and the discovery that there is almost no water vapor in Venus’ thick carbon-dioxide atmosphere. The next “stop” for Galileo is Earth, mere months later.

NASA/JPL’s Galileo space probe – eventually bound for Jupiter – reaches the first destination on its looping “VEEGA” (Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist) trajectory, the planet Venus. This flyby of Venus allows for testing of Galileo’s cameras and other science instruments, offering the first near-infrared views of the planet’s dense clouds, and the discovery that there is almost no water vapor in Venus’ thick carbon-dioxide atmosphere. The next “stop” for Galileo is Earth, mere months later.

STS-34

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifts off on a mission lasting nearly five days, whose primary goal is to lift the interplanetary probe Galileo into orbit. Originally intended for launch in late 1982, Galileo is bound for Jupiter by way of a long, looping trajectory that sends it to Venus and back to Earth multiple times, picking up speed via gravitational assist with each visit. Galileo won’t actually reach Jupiter itself until December 1995. Aboard Atlantis for this flight are Commander Donald Williams, Pilot Michael McCulley, and mission specialists Franklin Chang-Diaz, Shannon Lucid, and Ellen S. Baker.

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifts off on a mission lasting nearly five days, whose primary goal is to lift the interplanetary probe Galileo into orbit. Originally intended for launch in late 1982, Galileo is bound for Jupiter by way of a long, looping trajectory that sends it to Venus and back to Earth multiple times, picking up speed via gravitational assist with each visit. Galileo won’t actually reach Jupiter itself until December 1995. Aboard Atlantis for this flight are Commander Donald Williams, Pilot Michael McCulley, and mission specialists Franklin Chang-Diaz, Shannon Lucid, and Ellen S. Baker.

The People vs. Galileo?

A lawsuit, filed by environmental activists worried about the release of plutonium from the Galileo Jupiter probe’s radioisotope thermoelectric generators in the event of a Challenger-like disaster during launch, is dismissed by a federal judge; the President of the United States has also given permission for the launch to proceed (a requirement anytime a nuclear-fueled spacecraft is in the works). The suit, filed earlier in the year, sought an injunction to prevent Galileo from being launched. Times have changed since the last RTG-powered flight (the Voyager missions of the 1970s), and activists are concerned about a Chernobyl-style radioactive disaster, although the plutonium 238 at the heart of Galileo’s power supply (and that of other interplanetary probes that have used it) is non-weapons-grade and non-fissible. Galileo is slated to be launched in a week aboard the space shuttle Atlantis.

A lawsuit, filed by environmental activists worried about the release of plutonium from the Galileo Jupiter probe’s radioisotope thermoelectric generators in the event of a Challenger-like disaster during launch, is dismissed by a federal judge; the President of the United States has also given permission for the launch to proceed (a requirement anytime a nuclear-fueled spacecraft is in the works). The suit, filed earlier in the year, sought an injunction to prevent Galileo from being launched. Times have changed since the last RTG-powered flight (the Voyager missions of the 1970s), and activists are concerned about a Chernobyl-style radioactive disaster, although the plutonium 238 at the heart of Galileo’s power supply (and that of other interplanetary probes that have used it) is non-weapons-grade and non-fissible. Galileo is slated to be launched in a week aboard the space shuttle Atlantis.

Galileo is go for VEEGA

After the cancellation of the Centaur liquid-fueled propulsion module – considered too risky for use aboard the space shuttle, all aspects of which are now under a wide-ranging government review after the Challenger disaster – NASA/JPL’s Galileo Jupiter probe is to begin undergoing modifications for a long, looping trajectory developed by Dr. Roger Diehl and dubbed “VEEGA” – Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist. (Another nickname for this new trajectory, the Solar Cruiser, doesn’t stick in acronym-happy NASA.) VEEGA will see Galileo taking an extra four years to reach Jupiter, getting gravity assists from the planets of the inner solar system during those additional years. Galileo must be modified because it was designed for outer solar system exploration, not exposure to solar heating and radiation within 1 AU of the sun. Since the primary high-gain antenna must be pointed away from Earth during some of this flight, NASA adds a medium-gain antenna to the spacecraft – a last-minute modification which will save the mission when the high-gain antenna fails to open on schedule. Galileo is scheduled for launch via space shuttle in 1989.

After the cancellation of the Centaur liquid-fueled propulsion module – considered too risky for use aboard the space shuttle, all aspects of which are now under a wide-ranging government review after the Challenger disaster – NASA/JPL’s Galileo Jupiter probe is to begin undergoing modifications for a long, looping trajectory developed by Dr. Roger Diehl and dubbed “VEEGA” – Venus/Earth/Earth Gravity Assist. (Another nickname for this new trajectory, the Solar Cruiser, doesn’t stick in acronym-happy NASA.) VEEGA will see Galileo taking an extra four years to reach Jupiter, getting gravity assists from the planets of the inner solar system during those additional years. Galileo must be modified because it was designed for outer solar system exploration, not exposure to solar heating and radiation within 1 AU of the sun. Since the primary high-gain antenna must be pointed away from Earth during some of this flight, NASA adds a medium-gain antenna to the spacecraft – a last-minute modification which will save the mission when the high-gain antenna fails to open on schedule. Galileo is scheduled for launch via space shuttle in 1989.

Galileo, Magellan go back to the shop

NASA informs the project managers of the Galileo and Magellan interplanetary probes – both of which were due to be launched via space shuttle – that their planned launches are obviously off the schedule due to the destruction of space shuttle Challenger and her crew. Further changes in the shuttle program in the wake of the tragedy will have far-reaching effects, including the cancellation of propulsion modules that would have allowed, for example, Galileo to be put on a direct trajectory toward Jupiter. The Galileo mission plan will undergo significant changes, including the loss of a planned visit to asteroid 29 Amphitrite, and both missions will eventually begin from the cargo bay of space shuttle missions in 1989.

NASA informs the project managers of the Galileo and Magellan interplanetary probes – both of which were due to be launched via space shuttle – that their planned launches are obviously off the schedule due to the destruction of space shuttle Challenger and her crew. Further changes in the shuttle program in the wake of the tragedy will have far-reaching effects, including the cancellation of propulsion modules that would have allowed, for example, Galileo to be put on a direct trajectory toward Jupiter. The Galileo mission plan will undergo significant changes, including the loss of a planned visit to asteroid 29 Amphitrite, and both missions will eventually begin from the cargo bay of space shuttle missions in 1989.

Jupiter probe, Space Telescope approved

Congress approves the largest NASA budget in ten years, including authorization and funding for two major unmanned spacecraft: a Space Telescope to be deployed into Earth orbit via Space Shuttle, and a yet-to-be-named Jupiter orbiter and atmospheric probe, originally proposed in the late 1960s as part of the outer planets Grand Tour mission plan. The Jupiter probe, which must be ready to launch in 1982 to take advantage of a planetary configuration providing the shortest distance between Earth and Jupiter, is the subject of a fierce budget fight in Congress. (This spacecraft will go on to be named Galileo.)

Congress approves the largest NASA budget in ten years, including authorization and funding for two major unmanned spacecraft: a Space Telescope to be deployed into Earth orbit via Space Shuttle, and a yet-to-be-named Jupiter orbiter and atmospheric probe, originally proposed in the late 1960s as part of the outer planets Grand Tour mission plan. The Jupiter probe, which must be ready to launch in 1982 to take advantage of a planetary configuration providing the shortest distance between Earth and Jupiter, is the subject of a fierce budget fight in Congress. (This spacecraft will go on to be named Galileo.)