Click here to see the complete list of YouTube videos

Welcome to one of the web’s oldest and most-respected repositories of information and critiques on classic video games: Phosphor Dot Fossils. You’ll find hundreds of reviews here, covering vintage arcade games, classic console games and long-forgotten early home computer software. The reviews here judge these games not by what technology has made possible since then, but by what was possible at the time of the game’s release. The articles here attempt to put each game into the context of its time; even more context can be gleaned by viewing the entire timeline, placing everything in a wider pop-cultural and historical context; the timeline can also be browsed by any day of the year, or by any year.

Welcome to one of the web’s oldest and most-respected repositories of information and critiques on classic video games: Phosphor Dot Fossils. You’ll find hundreds of reviews here, covering vintage arcade games, classic console games and long-forgotten early home computer software. The reviews here judge these games not by what technology has made possible since then, but by what was possible at the time of the game’s release. The articles here attempt to put each game into the context of its time; even more context can be gleaned by viewing the entire timeline, placing everything in a wider pop-cultural and historical context; the timeline can also be browsed by any day of the year, or by any year.

Browse Games By Year

1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979

1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987

1990 2000

Phosphor Dot Fossils covers all hardware platforms, but special emphasis is placed on arcade games, which set the standards to which home consoles and computers had to at least attempt to rise, often with far more limited resources for memory and graphics. More than a few still-thriving franchises were born in massive plywood cabinets that took our quarters and our time in the 1970s and 1980s.

Phosphor Dot Fossils covers all hardware platforms, but special emphasis is placed on arcade games, which set the standards to which home consoles and computers had to at least attempt to rise, often with far more limited resources for memory and graphics. More than a few still-thriving franchises were born in massive plywood cabinets that took our quarters and our time in the 1970s and 1980s.

We frequently follow these arcade hits home, where they appeared on numerous consoles and computers that were underpowered compared to their coin-op counterparts. But despite memory and hardware limitations, consoles – and their brilliant game designers and programmers – found ways to excel at games that simply weren’t suited to the arcade environment, where a never-ending stream of quarters was more important than a “deep” gaming experience that might last for more than a few minutes. There was room for both kinds of games back then – and there still is.

We frequently follow these arcade hits home, where they appeared on numerous consoles and computers that were underpowered compared to their coin-op counterparts. But despite memory and hardware limitations, consoles – and their brilliant game designers and programmers – found ways to excel at games that simply weren’t suited to the arcade environment, where a never-ending stream of quarters was more important than a “deep” gaming experience that might last for more than a few minutes. There was room for both kinds of games back then – and there still is.

Browse Games By System / Hardware Platform

Phosphor Dot Fossils covers arcade, console and computer games – as well as, to a slightly lesser extent, non-programmable dedicated game consoles and handheld and portable games. In some cases, where classic game franchises have continued to emerge through the 1990s and the 21st century, we follow those games too, whether they’re “greatest hits” collections of classic games, or complete remakes with modern graphics and sound. We also cover imported games never released in North

Phosphor Dot Fossils covers arcade, console and computer games – as well as, to a slightly lesser extent, non-programmable dedicated game consoles and handheld and portable games. In some cases, where classic game franchises have continued to emerge through the 1990s and the 21st century, we follow those games too, whether they’re “greatest hits” collections of classic games, or complete remakes with modern graphics and sound. We also cover imported games never released in North  America, newly-programmed “homebrew games” for classic systems, and even games that never saw the light of day.

America, newly-programmed “homebrew games” for classic systems, and even games that never saw the light of day.

Along the way, there is a single narrative being told by this multimedia study of classic games: it’s the creation and rise of an industry that now dominates the entertainment landscape, and the advancement of multiple technologies whose effects can be felt far beyond our living rooms. Controversies have come and gone, but the medium of the video game is here to stay.

This is how it all started, and how it evolved from there.

Welcome to Phosphor Dot Fossils.

Stay and play.

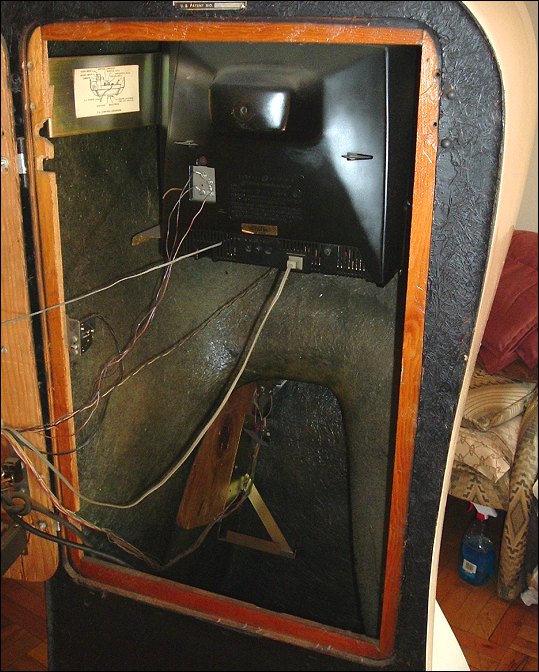

In the spring of 2007, amid some controversy and skepticism from the collecting community, a machine identified as the one and only white

In the spring of 2007, amid some controversy and skepticism from the collecting community, a machine identified as the one and only white

The Game: A simple version of video ping-pong; players use three knobs, one to control horizontal movement, one to control vertical movement, and a third to control the “English” or spin of the ball. (Magnavox, 1975)

The Game: A simple version of video ping-pong; players use three knobs, one to control horizontal movement, one to control vertical movement, and a third to control the “English” or spin of the ball. (Magnavox, 1975) Talk about upscale. The Odyssey 200, released not long after the

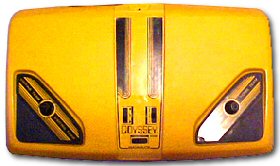

Talk about upscale. The Odyssey 200, released not long after the  Taking Atari’s lead for the first time, the Odyssey 300 – in its bright yellow shell – saw the console abandoning the trio of horizontal/vertical/English controls that had been in place since the original Odyssey. In addition to mimicking the all-in-one controls of Atari’s Pong, Odyssey 300 – still boasting the standard Tennis, Hockey and Smash variations of its predecessors – introduced digital on-screen scoring. The Odyssey games were no longer reliant on the honor system: at 15 points, one player won the game.

Taking Atari’s lead for the first time, the Odyssey 300 – in its bright yellow shell – saw the console abandoning the trio of horizontal/vertical/English controls that had been in place since the original Odyssey. In addition to mimicking the all-in-one controls of Atari’s Pong, Odyssey 300 – still boasting the standard Tennis, Hockey and Smash variations of its predecessors – introduced digital on-screen scoring. The Odyssey games were no longer reliant on the honor system: at 15 points, one player won the game.  The Game: You control a dot making its way through a twisty maze with two exits – one right behind you and one across the screen from you. The computer also controls a dot which immediately begins working its way toward the exit behind you. The game is simple: you have to guide your dot through the maze to the opposite exit before the computer does the same. If the computer wins twice, the game is over. (Midway, 1976)

The Game: You control a dot making its way through a twisty maze with two exits – one right behind you and one across the screen from you. The computer also controls a dot which immediately begins working its way toward the exit behind you. The game is simple: you have to guide your dot through the maze to the opposite exit before the computer does the same. If the computer wins twice, the game is over. (Midway, 1976) The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Ramtek, 1976)

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Ramtek, 1976) The Game: Two players control one car each, careening freely around an arena filled with zombies. Faced with zombie-fication at the pedestrian crossing of the undead, the drivers have only one option: run over their opponents! Each zombie that’s squashed leaves a grave marker behind that becomes an unmovable obstacle to zombies and cars alike. Whoever has run over the most zombies by the end of the timed game wins. (Exidy, 1976)

The Game: Two players control one car each, careening freely around an arena filled with zombies. Faced with zombie-fication at the pedestrian crossing of the undead, the drivers have only one option: run over their opponents! Each zombie that’s squashed leaves a grave marker behind that becomes an unmovable obstacle to zombies and cars alike. Whoever has run over the most zombies by the end of the timed game wins. (Exidy, 1976) With the same trio of games as the Odyssey 400 – Tennis, Hockey/Soccer and Smash – the Odyssey 500, released in 1976 by Magnavox, would appear to not be much of an upgrade, but in fact, it’s an absolutely critical turning point for home video games: the Odyssey 500 did away with squares and rectangles to represent the player, and introduced character sprites – hardware-generated characters that roughly mimicked the shape of a human being.

With the same trio of games as the Odyssey 400 – Tennis, Hockey/Soccer and Smash – the Odyssey 500, released in 1976 by Magnavox, would appear to not be much of an upgrade, but in fact, it’s an absolutely critical turning point for home video games: the Odyssey 500 did away with squares and rectangles to represent the player, and introduced character sprites – hardware-generated characters that roughly mimicked the shape of a human being.  The Game: Activated by leaving a cartridge out of the slot, powering the system up and pressing one of the selector keys, Tennis and Hockey are built into the system. Timed games can be selected, and the traditional rules of each sport apply. (Fairchild, 1976)

The Game: Activated by leaving a cartridge out of the slot, powering the system up and pressing one of the selector keys, Tennis and Hockey are built into the system. Timed games can be selected, and the traditional rules of each sport apply. (Fairchild, 1976) The Game: The first Channel F “Videocart” packs three games into one bright yellow package. Shooting Gallery is a straightforward target practice game in which players try to draw a bead on a moving target. Tic-Tac-Toe is the timeless game of strategy in small, enclosed spaces, and Quadradoodle is a simple paint program, long, long before its time. (Fairchild, 1976)

The Game: The first Channel F “Videocart” packs three games into one bright yellow package. Shooting Gallery is a straightforward target practice game in which players try to draw a bead on a moving target. Tic-Tac-Toe is the timeless game of strategy in small, enclosed spaces, and Quadradoodle is a simple paint program, long, long before its time. (Fairchild, 1976) After the baffling backward step of the Odyssey 400, Magnavox’s Odyssey 2000 saw a return to the Pong-inspired, single-paddle control scheme, with digital scoring restored as well – Magnavox had decided to rest the Brown Box design (and the subsequent variations on it) permanently in favor of, once again, the General Instruments AY-3-8500 “Pong on a chip” processor. Packaged in a red casing, this would be the last anyone would see of the smoothly rounded-off, integrated Odyssey console. The next system to bear the name would return to its roots – with wired controllers that weren’t necessarily stuck to the main console – and look forward, with a futuristic new design that stands up even today.

After the baffling backward step of the Odyssey 400, Magnavox’s Odyssey 2000 saw a return to the Pong-inspired, single-paddle control scheme, with digital scoring restored as well – Magnavox had decided to rest the Brown Box design (and the subsequent variations on it) permanently in favor of, once again, the General Instruments AY-3-8500 “Pong on a chip” processor. Packaged in a red casing, this would be the last anyone would see of the smoothly rounded-off, integrated Odyssey console. The next system to bear the name would return to its roots – with wired controllers that weren’t necessarily stuck to the main console – and look forward, with a futuristic new design that stands up even today.  It adds nothing to the Odyssey 2000’s “four action-packed video games,” but the Odyssey 3000 is a quantum leap in the design aesthetic of the console itself. Finally breaking away from the basic casing design that had been in place since the Odyssey 100, Odyssey 3000 packs four games (well, really just three plus a Tennis “practice mode”) into a sleek, futuristic-looking black wedge with highlights that almost anticipate – believe it or not – the look of the computer screens in Star Trek: The Next Generation (though to be more realistic, it may have been influenced by the design line of Atari’s Fuji logo). The controllers are detachable but hardwired, and nestle snugly into the console itself.

It adds nothing to the Odyssey 2000’s “four action-packed video games,” but the Odyssey 3000 is a quantum leap in the design aesthetic of the console itself. Finally breaking away from the basic casing design that had been in place since the Odyssey 100, Odyssey 3000 packs four games (well, really just three plus a Tennis “practice mode”) into a sleek, futuristic-looking black wedge with highlights that almost anticipate – believe it or not – the look of the computer screens in Star Trek: The Next Generation (though to be more realistic, it may have been influenced by the design line of Atari’s Fuji logo). The controllers are detachable but hardwired, and nestle snugly into the console itself.  The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Midway, 1977)

The Game: Up to four players control markers that leave a solid “wall” in their wake. The object of the game is to trap the other players by building a wall around them that they can’t avoid crashing into – or forcing them to crash into their own walls. Run into a wall, either your own or someone else’s, ends your turn and erases your trail from the screen (potentially eliminating an obstacle for the remaining players). The player still standing at the end of the round wins. (Midway, 1977) The Game: It’s a day at the digital ballpark for two players; the game is very simple – players control the timing of pitches and batting, which will determine how the game unfolds. The highest score at the end of nine innings wins. (RCA, 1977)

The Game: It’s a day at the digital ballpark for two players; the game is very simple – players control the timing of pitches and batting, which will determine how the game unfolds. The highest score at the end of nine innings wins. (RCA, 1977) The final member of the Odyssey stand-alone console family tree, the Odyssey 4000 boasts more games than any of its predecessors since Ralph Baer’s original Odyssey, and was only the second of the dedicated Odyssey consoles to feature color (after the experimental Odyssey 500). And for those who have ever held the joystick of a Magnavox Odyssey² in their hands, the Odyssey 4000 offers another familiar element – its joysticks are exactly the same mold as those of the Odyssey², only rotated 90 degrees, and sporting some major differences in internal mechanisms. Though multidirectional, the joysticks are designed to favor vertical movement and offer some resistance to horizontal movement.

The final member of the Odyssey stand-alone console family tree, the Odyssey 4000 boasts more games than any of its predecessors since Ralph Baer’s original Odyssey, and was only the second of the dedicated Odyssey consoles to feature color (after the experimental Odyssey 500). And for those who have ever held the joystick of a Magnavox Odyssey² in their hands, the Odyssey 4000 offers another familiar element – its joysticks are exactly the same mold as those of the Odyssey², only rotated 90 degrees, and sporting some major differences in internal mechanisms. Though multidirectional, the joysticks are designed to favor vertical movement and offer some resistance to horizontal movement.  The Game: Piloting a mobile cannon around a cluttered playfield, you have but one task: clear the screen of mines, without blowing yourself up, in the time allotted. If you don’t clear the screen, or you manage to detonate a mine so close to yourself that it takes you out, the game is over. If you do clear all the mines, you get a free chance to try it again. Two players can also try to clear the minefield simultaneously. (Gremlin, 1978)

The Game: Piloting a mobile cannon around a cluttered playfield, you have but one task: clear the screen of mines, without blowing yourself up, in the time allotted. If you don’t clear the screen, or you manage to detonate a mine so close to yourself that it takes you out, the game is over. If you do clear all the mines, you get a free chance to try it again. Two players can also try to clear the minefield simultaneously. (Gremlin, 1978) The Game: Long before Frogger and Frog Bog, there were simply Frogs, the original arcade amphibians. One or two frogs hop along a lily pad at the bottom of the screen, scoping out tasty flies to eat. When you’ve got a morsel in your frog’s reach, jump and try to activate your frog’s tongue at just the right time. (You’ll know if you’ve snared a meal because your frog will seem to ascend the screen in heavenly bliss.) Whoever has the most points at the end of the timed game is the supreme frog. (Gremlin, 1978)

The Game: Long before Frogger and Frog Bog, there were simply Frogs, the original arcade amphibians. One or two frogs hop along a lily pad at the bottom of the screen, scoping out tasty flies to eat. When you’ve got a morsel in your frog’s reach, jump and try to activate your frog’s tongue at just the right time. (You’ll know if you’ve snared a meal because your frog will seem to ascend the screen in heavenly bliss.) Whoever has the most points at the end of the timed game is the supreme frog. (Gremlin, 1978) The Game: It’s like pinball, but not quite. Not only are the bouncing-ball physics and bumpers of pinball present, but so are walls of bricks which, when destroyed, add to your score and sometimes redirect your ball in unpredictable directions. Pinball meets Breakout. (Namco, 1978)

The Game: It’s like pinball, but not quite. Not only are the bouncing-ball physics and bumpers of pinball present, but so are walls of bricks which, when destroyed, add to your score and sometimes redirect your ball in unpredictable directions. Pinball meets Breakout. (Namco, 1978)

The Game: A virtual pinball machine is presented, complete with flippers, bumpers, and the ability to physically “bump” the table to influence the motion of the ball. Per standard pinball rules, the object of the game is to keep the ball in play as long as possible. (Ralph Baer, 1978 – unreleased prototype)

The Game: A virtual pinball machine is presented, complete with flippers, bumpers, and the ability to physically “bump” the table to influence the motion of the ball. Per standard pinball rules, the object of the game is to keep the ball in play as long as possible. (Ralph Baer, 1978 – unreleased prototype) The Game: War is pixellated, blocky hell on the Odyssey²! In Armored Encounter, two combatants in tanks circumnavigate a maze peppered with land mines, searching for the optimum spot from which to blow each other to kingdom come. In Sub Chase, a bomber plane and a submarine, both maneuverable in their own way, try to take each other out without blasting any non-combatant boats routinely running between them (darn that civilian shipping!). In both games, the timer is counting down for both sides to blow each other straight to hell. (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: War is pixellated, blocky hell on the Odyssey²! In Armored Encounter, two combatants in tanks circumnavigate a maze peppered with land mines, searching for the optimum spot from which to blow each other to kingdom come. In Sub Chase, a bomber plane and a submarine, both maneuverable in their own way, try to take each other out without blasting any non-combatant boats routinely running between them (darn that civilian shipping!). In both games, the timer is counting down for both sides to blow each other straight to hell. (Magnavox, 1978) The Game: In Baseball!, you are, quite simply, one of two teams playing the great American game. If you’re up at bat, your joystick and button control the man at the plate and any players on base. If you’re pitching, your button and joystick control how wild or straight your pitches are, and you also control the outfielders – you can catch a ball on the fly, or pick it up and try to catch the other player away from his bases. (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: In Baseball!, you are, quite simply, one of two teams playing the great American game. If you’re up at bat, your joystick and button control the man at the plate and any players on base. If you’re pitching, your button and joystick control how wild or straight your pitches are, and you also control the outfielders – you can catch a ball on the fly, or pick it up and try to catch the other player away from his bases. (Magnavox, 1978) The Game: Hit the hardwood in one of two sports. Roll your big shiny one down the lanes and try to knock down all the pins in Bowling!, or go for a basket in Basketball! Not possible in Odyssey² Basketball!: fouls, three-point shots, free throws, most steals… (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: Hit the hardwood in one of two sports. Roll your big shiny one down the lanes and try to knock down all the pins in Bowling!, or go for a basket in Basketball! Not possible in Odyssey² Basketball!: fouls, three-point shots, free throws, most steals… (Magnavox, 1978) The Game: As man eked out his existence in the dark ages with only his animal cunning and the brutal power of the club, so do you in this golf simulation, in which you putter around nine different courses in an attempt to make a hole in one – or simply to stay under par. (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: As man eked out his existence in the dark ages with only his animal cunning and the brutal power of the club, so do you in this golf simulation, in which you putter around nine different courses in an attempt to make a hole in one – or simply to stay under par. (Magnavox, 1978) The Game: Trapped in a square or rectangular arena, the player is represented by a mobile square. Another projectile punches its way into the arena and begins ricocheting around; points accumulate rapidly the longer the player’s square avoids contact with the projectile, but starting at 200 points, an additional projectile is added every 100 points, each on its own chaotic, bouncing path. The game ends when the player inevitably collides with one of these projectiles. (Fairchild, 1978)

The Game: Trapped in a square or rectangular arena, the player is represented by a mobile square. Another projectile punches its way into the arena and begins ricocheting around; points accumulate rapidly the longer the player’s square avoids contact with the projectile, but starting at 200 points, an additional projectile is added every 100 points, each on its own chaotic, bouncing path. The game ends when the player inevitably collides with one of these projectiles. (Fairchild, 1978) The Game: Woooooo, Packers. Classic pigskin comes to sluggish life in this over-complicated video game edition. Despite the Odyssey’s full keyboard, the game forces players to look up plays in the manual and execute them with joystick commands. After that, aside from some minimal control of whoever has the ball, it’s a bit like watching an ant farm. (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: Woooooo, Packers. Classic pigskin comes to sluggish life in this over-complicated video game edition. Despite the Odyssey’s full keyboard, the game forces players to look up plays in the manual and execute them with joystick commands. After that, aside from some minimal control of whoever has the ball, it’s a bit like watching an ant farm. (Magnavox, 1978) The Game: Place your bets, ditch some cards, or play with the ones you’ve got. The computer offers the usual enticements – double down and insurance – but the odds are firmly in favor of the house. There’s no limit on how big your bet is, so you’re even free to bet an ante that’ll have you screaming “uncle!” if you lose. (Magnavox, 1978)

The Game: Place your bets, ditch some cards, or play with the ones you’ve got. The computer offers the usual enticements – double down and insurance – but the odds are firmly in favor of the house. There’s no limit on how big your bet is, so you’re even free to bet an ante that’ll have you screaming “uncle!” if you lose. (Magnavox, 1978)